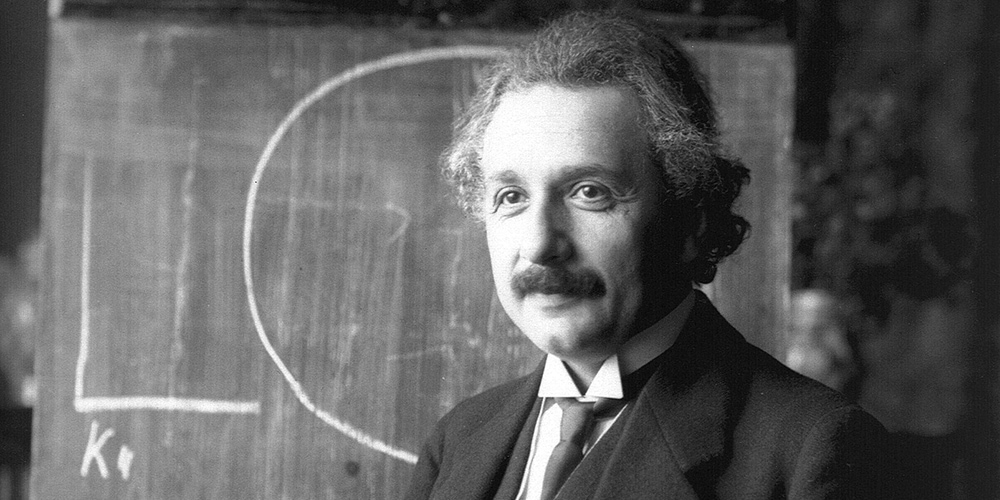

Most everyone knows the name, the face (the hair) of Albert Einstein, even if most everyone doesn’t know what he’s famous for except, perhaps, e=mc2, the formula that catapulted the species into the atomic era.

Unable to find a teaching job after completing his PhD, most likely because Einstein was such a smart aleck that he ticked off his professors, the 26-year-old clerk in a Swiss patent office nevertheless published in 1905 four physics papers, any one alone enough to have established his credentials.

One paper verified the existence of atoms, which was still in question then. Another helped set the foundations of quantum physics, which overturned millennia of thought about reality. A third introduced the above-mentioned e=mc2. (“Oy Vey.” What Einstein uttered upon hearing about Hiroshima.)

Then there was the paper, titled innocuously enough, “On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies,” which theorized that the laws of physics remain the same in all frames of reference in uniform motion. However benign sounding, this conclusion, known as the Theory of Special Relativity, included the counterintuitive notion that time did not flow at the same rate for everyone, or everything, no matter what.

A common (but flawed) example is the “Twins’ Paradox.” One twin soars from earth through space in a rocket close to speed c, the speed of light, while the other remains on terra firma. When the rocket returns, the twin on earth aged 10 years while the twin in space aged only two. How could that be? It could be because time in the frame of reference for the twin booking through space so slowed that what took two years for her took 10 for her sister on earth.

Einstein’s theory worked only in special cases though: uniform (generally straight-line) motion at constant speed. Hence the appellation Special Relativity. But what about accelerating or decelerating non-uniform motion, the way that most things go from point A to point B? Einstein labored 10 more intense years until publishing, in 1915, his Theory of General Relativity, a radical new understanding of gravity (gravity was not a force, he said, but the curvature of space itself) that, if not upending Newton’s work, greatly limited its application.

However, General Relativity made inevitable what everyone knew impossible, and that was a non-static universe, a universe that was either contracting or expanding. Evidence, data, and common sense for centuries revealed that it did neither. So in order to avoid this embarrassing result, Einstein reluctantly conjured up a new term, the “cosmological constant,” and applied it to the field equations of his theory in order to keep the cosmos static. That’s right. He made it up and dropped it in, harmonizing theory with reality. (Yes, scientists sometimes do things like that.)

Unfortunately, Vesto Slipher, Alexander Friedmann, George Lemaître, and Edwin Hubble eventually showed that what everyone knew was true, a static universe, was false. So in 1931, Einstein retracted his “cosmological constant,” reputedly calling it his “biggest blunder” because the universe was, in fact, expanding.

Not only expanding, but according to received wisdom, expanding faster than Einstein’s field equations allowed for. Therefore, in another attempt to harmonize theory and reality, scientists have re-introduced something like Einstein’s “cosmological constant,” only now not to keep the universe static but to keep it expanding. The reason for this unexpected rate of expansion is, they claim, that 74 percent of the universe is composed of dark energy, “dark” because scientists remain in the dark about what this energy might be.

Even worse, because present theories cannot explain why galaxies rotate at the speeds they do, scientists claim that 22 percent of the universe is made of dark matter, as well.

Maybe I’m revealing my ignorance here, but are cosmologists so wedded to their formulas and theories that, rather than revise or discard them, they speculate that 96 percent of the universe is composed of unknown, unseen, and undetected matter and energy? A rather extreme move, is it not, just to save their theories? Might they not re-think their theories rather than reconfigure 96 percent of the cosmos in order to make it fit those theories?

Or suppose the vast universe that we see, the billions of galaxies spanning billions of light years of space and time, does compose only 4 percent of creation? Talk about wallowing in ignorance, or seeing “through a glass, darkly” (1 Cor. 13:12, KJV). If cosmologists are correct about dark matter and dark energy, it would mean that we know so much less about the created world than we had imagined. And of what we do know—and are so sure about that we award Nobel Prizes for it—how much of that will one day be falsified, as so much knowledge has already been? What percentage of the world’s wisdom, its vaunted and celebrated wisdom, “is foolishness in God’s sight” (1 Cor. 3:19) anyway?

Probably more than we realize and, Oy Vey, more than we can begin to know.

Clifford Goldstein is editor of the Adult Sabbath School Bible Study Guide. His latest book, Baptizing the Devil: Evolution and the Seduction of Christianity, was recently released by Pacific Press.