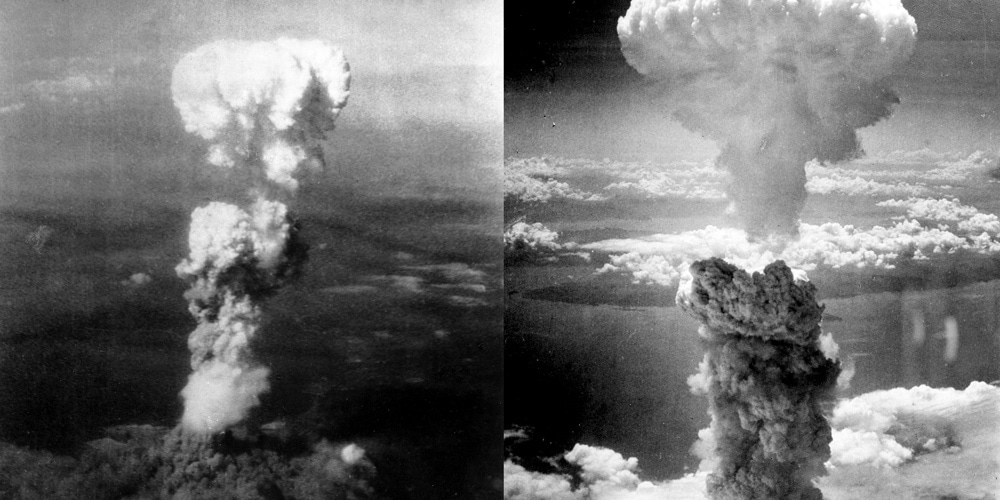

On a sunny Monday morning on August 6, 1945, an American B-29 bomber dropped the first nuclear bomb on the Japanese port city of Hiroshima. The 4.4-ton heavy device, containing 60 kilograms of uranium, exploded at 8:15 a.m. local time and caused the immediate death of an estimated 70,000 people and the protracted, often lasting a lifetime, suffering of tens of thousands.1 Three days later, on August 9, 1945, a second nuclear device was dropped on Nagasaki, killing tens of thousands more. The Pacific War came to an end on August 14 (August 15 in Japan), and the formal surrender of Japan to the allied forces was signed on September 2, 1945.2 Seventy-five years later we remember the victims and the events that changed the course of history.

Many historians suggest that while the bombs may have shortened the duration of the war in the Pacific, and, consequently, saved hundreds of thousands of American and Japanese soldiers and civilians, dropping the atomic bombs was not necessary for the Allies to win the war. One well-documented analysis asserts that the bombs were intended by the United States government to be a clear message to the erstwhile ally, the Soviet government, as part of a political calculation in an increasingly tense relationship.3

The following decades were marked by the Cold War. Generations of people from around the globe have lived under its shadow since then. When the Soviet Union acquired nuclear capabilities, the world found itself in a stalemate. East and West continued to build up their ability to destroy every living being on Planet Earth again and again. Other countries joined the nuclear power club. Deterrence became the keyword of diplomacy.

Nuclear deterrence was built on fear. If you send your intercontinental ballistic missiles (IBMs), destroying every major city in my country, I will retaliate by sending my IBMs, making sure that nothing and no one will survive in your country. Fear of annihilation and total destruction kept the missiles in their silos. The balance of fear worked—even though only barely. Those who remember the Cuban Missile Crisis and have read documents related to these tense moments recognize that the world was very close to war—and potentially complete destruction—during those months.

The fall of the Berlin Wall and the apparent demise of communism in 1989 seemed to usher in more hopeful times. This window of opportunity, however, was short-lived. Since then our planet hasn’t become a safer place. Fears on a global scale impact everyone: wars in the Middle East affecting the entire world; terrorist threats in every corner of the planet; the menace of biological warfare; and, now, the strangling grip of a virus touching every nation. There is no balance of fear that will ever produce something good.

No one—generals or civilians—can fully anticipate how the decisions made under the reign of fear will change either national or personal history, and none of us would trade our moment 75 years later for the fearful decisions taken long ago. Fear perpetuates itself, until those who could be friends and partners dissolve into nationalistic, tribal, or racial antagonists.

Fear often also drives many of our decisions. In the midst of a pandemic we’re afraid of the future. We fear the effect of the virus on our health. We wonder if we will be the next to lose our jobs. We are anxious for our children or grandchildren. Fear has a tendency to suck joy, happiness, and contentment out of our existence. Life based on a balance of fear is not a God-centered life.

Scripture tells us that there’s only one antidote: “There is no fear in love. But perfect love drives out fear, because fear has to do with punishment. The one who fears is not made perfect in love” (1 John 4:18, NIV).4 Perfect love drives out fear uses a very strong verbal form in the original Greek text. It suggests radical removal. Fear needs to be given to the One who overcame fear—and judgment and death. His love can overcome our fears. His grace can transform our trembling hearts. His compassion reaches out to everyone, regardless of gender, race, nationality, income, and education. There is no balance of fear in God’s government.

Gerald A. Klingbeil is a native of Germany and serves as an associate editor for Adventist Review Ministries.

2https://www.britannica.com/place/Japan/World-War-II-and-defeat.

3Gar Alperovitz, “Did America Have to Drop the Bomb? Not to End the War, But Truman Wanted to Intimidate Russia,” The Washington Post(Aug. 4, 1985), online at https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/opinions/1985/08/04/did-america-have-to-drop-the-bombnot-to-end-the-war-but-truman-wanted-to-intimidate-russia/46105dff-8594-4f6c-b6d7-ef1b6cb6530d/.

4Texts credited to NIV are from the Holy Bible, New International Version. Copyright ã 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide.