BY MILDRED THOMPSON OLSON

This story first appeared in the July 22, 2004,

issue of the Adventist Review

HE JOB WOULD NEVER make him rich, but the view certainly had its consolations.

HE JOB WOULD NEVER make him rich, but the view certainly had its consolations.

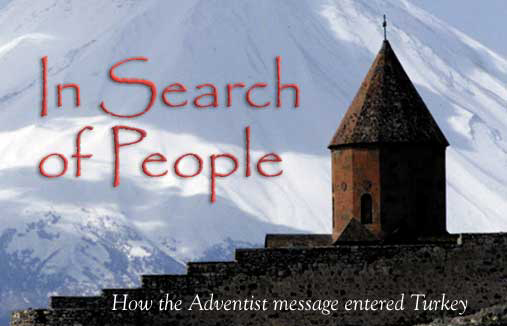

Theodore Anthony was a poor cobbler living in an obscure village

at the foot of Mount Ararat, the lofty mountain from which Noah left the ark.

While sewing soles to leather uppers or hammering heels into place, he frequently

looked up to the snowcapped heights and thought of the old Bible story. It was

a story filled with great drama and great grace, both of which his life seemed

to lack, and it featured the actions of a God who intervened in the lives of

those who were faithful to Him. Was that God still watching the world as closely

in the middle of the nineteenth century as He had millennia before? Did He still

care for the weak and the helpless, and for those who sought to order their

lives by His requirements? Did the God of the Bible story have time to notice

an insignificant soul who tapped out a living on a cobbler's bench?

Theodore believed in God, but truth be told, he wondered if

God believed in him. He was nominally religious, but never certain that he had

grasped what all the ceremony and mystery of his traditional religion pointed

to. Born and baptized into the Greek Orthodox faith, he attended worship regularly

and confessed his sins honestly. Somehow, though, despite his best intentions,

the peace and satisfaction that he sought from his faith always seemed to elude

him. Theodore longed to know that his sins were forgiven and to feel

the love of God. But try as he would, the object of his faith seemed as remote

and mysterious as the icy heights of the mountain that loomed over his village.

So Theodore dreamed instead of a future on earth--a future in

which he could earn enough money to buy a small house, own a suit of clothes,

and have sufficient food to fill his stomach. For a Christian living in Turkey

in the 1850s, these too were heady dreams, and not ones ever likely to be realized.

Making and repairing shoes might keep a body alive, but it did little to move

the spirit forward. The drudgery of everyday life was cloying and unshakable.

People in his village often talked about America, an earthly

paradise (so they said) where everyone had plenty. Like so many others, Theodore

dreamed of going there. At 21 he journeyed to the American Consulate in Constantinople

(Istanbul) and had his name placed on the United States immigration list. While

he waited for his name to work its way to the top of the list, Theodore lived

with his Greek parents in the old brick-and-wood house in which he had been

born.

People in his village often talked about America, an earthly

paradise (so they said) where everyone had plenty. Like so many others, Theodore

dreamed of going there. At 21 he journeyed to the American Consulate in Constantinople

(Istanbul) and had his name placed on the United States immigration list. While

he waited for his name to work its way to the top of the list, Theodore lived

with his Greek parents in the old brick-and-wood house in which he had been

born.

His cobbler's trade was an itinerant profession and kept him

traveling from village to village, staying in the homes of clients while he

made shoes for their families. It was a hard, uncomfortable life, but he managed

to earn enough money to keep himself solvent. He lived frugally, tucking away

a few lira each week from his meager earnings. Sometimes he removed the savings

from his old sock and counted his money, wondering when there might be enough

to buy his passage to America. Someday his name would be called at the consulate,

and the lack of money must not stop him from fulfilling his dream. The yearly

immigrant quota from Turkey to the United States was very small, and it might

be many years before his name would top the list. For now he could only work

and wait and hope.

A Long Waiting

During the next two decades as Theodore waited for his better life, his parents

grew old and died, and the siblings who had survived childhood left the family

home one by one. Frequently alone and without many friends, Theodore was kept

going only by the hope of emigrating to America.

One happy spring day, the official notification finally arrived:

"Theodore Anthony has been cleared for emigration to the United States

of America." The pain of 28 years had finally ended, and Theodore cried

tears of joy. He wasted no time in packing his small trunk with his few possessions

and, of course, his cobbler's tools. From Constantinople he sailed to America,

certain that he was leaving his homeland forever.

Because Theodore understood Greek almost as well as Turkish,

he settled in a Greek community in San Jose, California. He set up his cobbler's

shop in his abode, excited to be earning good pay for the first time in his

49 years. Though it might not be quite the paradise of which he had been told,

the United States offered him opportunities that never could have been his in

Turkey. Nothing could lure him back to the land of his birth.

By living parsimoniously, he was able to purchase a modest home

and set up a shoe shop in the front part of the residence. In less than a year

he had fulfilled his dream--a house, a business, and sufficient food. Satisfying

as those things were, the peace and security he enjoyed in America topped his

list of blessings. From a land where Christians were frequently and violently

persecuted by adherents of the majority religion, he now resided in a place

where he was free to believe and practice whatever he wished. He would never

face that danger again.

Prophecy Under the Big Top

The new land also invited new routines. Every evening Theodore enjoyed taking

a walk around his community, talking with passersby, enjoying the coolness of

the dusk. One night he noticed that a tent had been set up in an empty lot near

his home. He had heard of America's circuses and had decided to see one for

himself as soon as possible.

"My fortune is better than I could imagine," Theodore

said to himself, smiling with satisfaction. "Here is the circus I've always

wanted to see, and it's within walking distance of my home. I've worked hard

and deserve to treat myself to a diversion now and then. I shall attend it!"

He walked across the street to read the large sign posted in

front of the big top. The sign was in English: All he could discern was the

starting time of 7:00 p.m. It was obvious that there would be no show that night

since everything was closed up and dark.

The next evening Theodore washed, dressed in his baggy wool

pants and a clean shirt, and walked to the tent before the time appointed. Yet

still there was no ticket booth, no clowns, no elephants, nor any visible signs

of the circus. The tent flap, however, was open, and two men greeted him with

a warm smile and handshake. They handed him a song sheet, which he couldn't

read, and showed him to a plank bench.

Where are the bleachers? Where is the circus ring? Where

are the trapeze ropes and other paraphernalia? he wondered. All he could

see were planks for seating and a p1atform featuring an old pump organ. He was

puzzled by this unusual "circus," but now that he was here, he might

as well stay. He had nothing else to do, and it hadn't cost him a penny.

Soon the tent filled with people. A man in a suit and tie (something

Theodore hoped to own himself one day) took the platform and began to sing.

Theodore was thrilled to hear the music director sing songs about Jesus in Turkish,

his native language. The pleasure was mitigated a bit, however, for all the

other people around him sang only in English.

A distinguished-looking man, also dressed in a suit and tie,

came to the platform and delivered a marvelous spiritual address, quoting many

scriptures directly from the Bible. The man spoke clearly in Turkish and gave

such an interesting talk that Theodore decided to return the next evening. It

was good to hear his own language again after living in the Greek community

for a year.

Theodore attended every subsequent meeting. The preacher portrayed

Jesus as a personal Savior, one who cared deeply for those who followed Him.

For the first time in his life Theodore felt God's love. He was thrilled

with what he was learning and shared it with his clients. Awed with the prophecies

in the biblical books of Daniel and Revelation, he placed his faith in the God

who revealed His secrets to humanity. Now he knew God personally and understood

why every person was important to Him. This was the God he had always yearned

to know, the God whom he had dreamed about while still a young man in the shadow

of Mount Ararat.

On the evening that the pastor called for those who wanted to

serve God completely to come forward in commitment, Theodore practically raced

to the front. But when the pastor examined the candidates for baptism, Theodore

was perplexed.

"Why don't you use the Turkish language to question us?"

he asked.

The pastor was aghast. He didn't understand a thing Theodore

said, nor did anyone else on the evangelistic team. They found a Greek in the

audience who translated for Theodore. It was then Theodore learned that no one

had either sung or spoken in Turkish. The news was overwhelming to the cobbler,

standing under the big tent, tears streaming down his face. The Holy Spirit

had been poured out on him in a most singular way--his private Pentecost had

caused him to hear in Turkish. As he marveled at the miracle, he prayed

that God would show him what he should do to help others learn the wonderful

plan of salvation that he now understood.

Theodore Anthony was baptized in the summer of 1888. He studied

his Greek Bible faithfully and tried to learn English so that he might enjoy

and participate in church services with fellow believers.

Home Again

After living in America for just two years, Theodore discovered that God had

a special job for him. In January of 1889 Theodore felt deeply impressed to

return to Turkey to preach the gospel message. The land of his birth, which

he had waited 28 years to leave, now beckoned him as it had once beckoned the

apostle Paul. Some might have circumvented the Spirit's call by offering excuses

or pointing to the previous providences of God that seemed to indicate another

direction. But Theodore obeyed the voice he had come to recognize. No sponsor

and no church were involved: no promises of financial support were made. Within

weeks he proceeded to sell his house and his business to become a self-supporting

missionary in Turkey.

"You are crazy to leave all you've dreamed of having

and return to Turkey," his Greek neighbors told him. "There's no future

for Christians there!"

Theodore knew how right they were, but God, who never makes

a mistake, had called him specifically. And Theodore responded, even

at the cost of his new and comfortable life in America.

Armed with Greek and Armenian Bibles and any literature he could

find in those languages, Theodore returned to Turkey. He was impressed to take

books and literature in English, French, and German, as well, even though he

could not read those languages himself, for someone else might need them. Thus

began the first permanent Seventh-day Adventist work in the Middle East.1

First Fruits

Thrilled with his message and empowered with the Holy Spirit, Theodore began

an aggressive work among the Christians of Constantinople. Predictably, there

was opposition: a Protestant missionary society heard of the enthusiastic evangelist

and almost immediately arranged to have him put into prison. Fighting his case

in court depleted his resources, so Theodore returned to his cobbler's bench

and witnessed as he worked. Poor and homeless again, he rented a room from an

Armenian acquaintance, Mr. Baharian.

When the landlord's son returned home from his school in Aintab

(now called Gaziantep) that summer, the young man met the new tenant and enjoyed

reading the books in English that Theodore brought to Turkey. Zadour Baharian's

two favorites were Uriah Smith's Daniel and the Revelation and J. N.

Andrews' History of the Sabbath. When he returned to his school in the

fall, Zadour took Theodore's English books with him. God seemed to speak to

him through the printed page, and he understood fully the message. The missionary

cobbler had won his first convert.

Word soon reached the Adventist mission in Europe that Adventism

had spread to Turkey. Elder H. P. Holser came from Germany to investigate, and

finding Zadour Baharian well taught, baptized him in the summer of 1890. Holser

also found the youth to be very articulate and intelligent, and urged Zadour

to consider ministerial training. Sensing that the hand of God was orchestrating

events, young Baharian traveled to Basel, Switzerland, and for the next two

years studied at the Adventist seminary there.

Because gospel literature had been so effective in bringing

him to a knowledge of the truth, Zadour was impressed to cyclostyle more than

10,000 pages of literature in the Turkish and Armenian languages while still

a student at Basel. When he returned to Turkey in 1892, he brought this work

with him. Reunited in ministry, Theodore Anthony and Zadour submitted the material

to a printer, who finally got permission to print it. Hundreds of pamphlets

were sent to acquaintances in 12 cities throughout Turkey.

In 1892 Zadour and Theodore held their first evangelistic meeting

in a rented hotel-house in Constantinople. The only young woman among the six

converts soon became Mrs. Baharian--a serendipity for the young preacher.

The literature scattered seeds of truth everywhere as friend

shared the good news with friend. Soon the two evangelists had more calls for

religious instruction than they could answer. In 1893 they held evangelistic

meetings in the cities where the literature work seemed to have aroused the

most interest: Ovajuk, Bardizag, Aleppo (now Malab, in Syria), and Alexandretta

(now Iskenderun). Church groups were formed, and the work in the land of the

seven churches of Revelation advanced rapidly under the leadership of the two

men.

H. P. Holser, by then president of the Central European Conference,

visited Turkey in 1894. In a sacred service he ordained Zadour Baharian to the

gospel ministry, making the young man the first national in the Middle East

to be so recognized by the young Adventist denomination.

The national government's Ministry of Religion granted only two types of missionary

permits--one to the Orthodox churches and the other to Protestants. The Orthodox

could not, and the Protestants would not, recognize Adventists, and so the church

in Turkey resorted to the same method for evangelism employed by the apostolic

church. Capable craftsmen settled in various territories of Turkey and plied

their trade while they witnessed for the truth. Theodore Anthony went to Brousa.

Two Armenians, a tailor and an umbrella maker, went to Nicodemia. A Greek artisan

went to Samsun; an Armenian carpenter moved to Adana. An Armenian colporteur

sold literature on the ships in Constantinople.

Worn out by his many labors, Theodore Anthony began to grow

ill. The years of travel, hard work, and opposition took their toll on the older

man. He died in 1895 at the age of 57, leaving a remarkable legacy of sacrifice

and dedication for Zadour Baharian and the growing numbers of new believers

throughout the country.

Growing Opposition

Just one year later these new Adventists who had learned the gospel from Theodore

were severely tested as a widespread campaign of violence against Christians

took the lives of many in the Christian community. During the persecution of

1896 many sought shelter in the Adventist meeting house in Constantinople. Miraculously,

not one of the new believers was killed in the widespread anti-Christian violence.

In spite of sporadic persecutions Adventist work advanced rapidly

under the leadership of the dauntless Baharian. Sabbath school lessons, tracts,

and books were translated and mailed from Constantinople, cementing the unity

among the believer groups that had developed in 40 cities of Turkey.

Baharian, like the apostle Paul, was a native of the Tarsus

district, and shared both the apostle's dauntless courage and his many sufferings.

From the start his ministry met with active persecution as he traveled throughout

Turkey and Armenia. He was repeatedly stoned, imprisoned, brought before tribunals,

and called on to face death on many occasions. In 1903 the government refused

to allow him freedom to circulate in Turkey. The next year he was limited to

his home province of Tarsus, but his disciples and converts scattered throughout

Turkey carried on in his absence. Zadour wrote with a Pauline pen, and his letters,

sometimes written behind prison bars, were filled with instruction and courage

for the young churches and new workers.

During one of the bleakest periods of persecution the four full-time

mission workers of Turkey sought to hold a workers' meeting to better coordinate

their work and encourage one another. Permission to meet was refused, as each

man was restricted to his province. Three of the workers were arrested separately,

however, and providentially were thrown into the same prison. Their joy was

complete when they found their leader, Zadour Baharian, in the same room. The

men rejoiced together and held their much-desired workers' meeting behind prison

bars. Upon their release from prison the four newly energized workers returned

to their respective fields to work in a more focused, if less obtrusive, manner.

The Christian population of Turkey suffered greatly between

1896 and the outbreak of the first World War. Localized and national campaigns

against Christians resulted in the deaths of thousands of Christians, many of

them Armenians, whose ethnicity and Christian faith were targeted by extremists.

The violence came terribly close to Zadour himself, as his wife and son were

shut up in the Adana prison in 1908, awaiting their execution. The night before

the day designated for a general attack upon Christians, a political turnabout

in the nation granted freedom of press and speech. The order was reversed from

"kill and slaughter" to "loose and protect" all Christians.

Other Adventist believers were not so fortunate. In 1909 Christians

in the Adana-Tarsus area were attacked. Six Adventist men were slain, some shot

in the back while they were kneeling in prayer. Others, including the Sabbath

school superintendent, were beaten and robbed, but escaped with their lives.

Following the methods once used by Theodore Anthony, Baharian

taught many young men to be colporteurs. Their sales kept the secretary busy

mailing them literature from the book depository in Constantinople. Though often

imprisoned and beaten, the colporteurs ranged the country, placing thousands

of pamphlets and books in homes. Their work was effective. By 1914 there were

342 known adult Adventists, though there may have been more.

Faithful to the End

Then came the fateful days of 1914-1915, when hundreds of thousands, perhaps

several million, Christians lost their lives through execution, persecution,

exile, and starvation. Some Christians were able to emmigrate or escape. Adventist

membership was reduced to less than 100. During the Armenian massacres of 1914-1915,

all but two of the colporteurs were martyred, though Baharian lived on.

Often falsely accused, Baharian appeared so many times before

Turkish tribunals that he became known among officials as "the Sabbatarian,"

a spiritual leader who never interfered in politics. He was usually quickly

released, but he lived constantly with the threat of incarceration and even

death.

The president of the Levant Mission asked Baharian to make a

missionary journey to the interior of Turkey to visit Adventist members. Since

the government had declared interior Turkey off-limits for all Armenians, this

was an extremely unwise directive. Church members begged the president to repudiate

his decision, for they knew that Zadour was almost certain to be killed. They

didn't want to lose their champion soulwinner, the man who dedicated his all

to Adventist work in Turkey, whether he held elected leadership positions or

not. No one could preach like Baharian: his sermons left them feeling that dew

from heaven had fallen upon them.

But Zadour Baharian considered a directive from the mission

president to be a call from God, and he cooperated with the unwise request.

The trip proved both fruitless and tragic. The members had already been killed

or exiled. There was no one to see or help. Zadour was caught, imprisoned, and

tortured. Two soldiers were sent to escort him back to Constantinople. Twenty

miles from Sivas and still nearly 200 miles east of Constantinople, the soldiers

stopped and told Baharian to deny Christ and profess his faith in Islam. This

the faithful minister refused to do. As he folded his hands in prayer, they

shot him, disposed of his body, and took his clothes to the market.2 The voice

of Turkey's modern apostle had gone silent.

In God's book of remembrance nothing good ever goes unnoticed.

And for the hundreds, even thousands, whose spiritual ancestry as Seventh-day

Adventists traces to the dedication of a patient cobbler and his first convert,

there will one day be a grand reunion with two of the Lord's most fearless servants

who showed with their lives what it means to carry His cross.

_________________________

1 Italian Seventh-day Adventists sent literature to friends in Alexandria, Egypt,

in 1877. A self-supporting missionary, Romualdo Bartola, visited there the following

year. His efforts resulted in seven converts. In 1879 Dr. Herbert Ribton went

to Alexandria to establish the work. However, he and two of his converts were

killed in a riot against foreigners in 1882. The group was scattered; it is

not clear that any permanent work remained in Egypt. Several Adventist Armenian

families, converts of Theodore Anthony and Zadour Baharian, moved from Turkey

to Cairo and Alexandria in 1897. It was then that an Adventist presence in Egypt

was permanently established.

2 During World War I one of the soldiers was captured by the British and taken

to a concentration camp in Egypt. There the soldier told an Adventist the sordid

story and expressed his regret for this senseless murder. This account, drawn

from eyewitness sources, differs from that offered in The Seventh-day Adventist

Encyclopedia.

_________________________

Mildred Thompson Olson, a retired teacher and a former missionary in Lebanon,

originally wrote this account in 1996. She drew some of her information from

two Armenians who had been won to Adventism by Zadour Baharian and had escaped

the 1914-1915 persecutions by fleeing to Beirut. They themselves heard from

Baharian the story of Theodore Anthony's remarkable dedication, as well as the

exploits of the younger man. Significant information was gleaned from the diaries

and memories of Diamondola Keanides Ashod, who had worked in the Constantinople

mission office and was closely associated with Baharian.