Religion played an important role in this empire, evidenced by the many temples located in the north of the country. Foremost among these is the 800-year-old Angkor Wat, thought to be the largest religious construction in the history of the world. Many of these temples and palaces are now in ruins, and the country is slowly rebuilding itself from the more recent horrors. Depending on which figures one uses, between 20 and 30 percent of the Cambodian population—approximately 3 million people—were killed in the five years of Pol Pot's Khmer Rouge in the late 1970s.

In addition, the many years of war have destroyed much of the country's infrastructure, leaving only limited resources for rebuilding. As in a number of Asian countries, Cambodia has an emerging AIDS crisis, while experiencing many of the other health problems found in the world's poorest countries.

"The best way I find to describe Cambodia and its problems is to compare it with a person who has great abilities but doesn't realize it because they have a low self-esteem," says Global Mission volunteer Ross McKenzie. "But Cambodia is a whole throbbing nation, and so living here and interacting with the people is like crawling into the mind of such a person and seeing how every part of the brain ticks and why it feels so low."

Yet Ross believes that Cambodia today is a far cry from what it was in the 1970s and even the early 1990s. And he is playing a role, however small, in providing hope to the people of this troubled land.

It was to have a profound effect on his family. "I eventually became a Seventh-day Adventist Christian. Two of my three brothers are Seventh-day Adventists, and my mother also attends church sometimes.

"I was shy and insecure—[problems that were] intensified by the divorce of my parents when I was 11—resulting in bad grades and behavior in high school," Ross recalls. "I read a Reader's Digest article about Ben Carson when I was 15, and it had a dramatic effect on my life. I found out only later he was a Seventh-day Adventist."

Ben Carson's story inspired Ross to continue with school, so he attended a church boarding school. During his two years there Ross's results showed continual improvement. "Not as outstanding as Ben Carson's, of course," he adds. "However, I am grateful that my life has been turning out for the better and not for the worse."

After boarding school Ross spent a year traveling around Australia, followed by two years working as a literature evangelist. He had plans to become a pastor and began studying. But he soon became frustrated with his studies. He didn't feel called to be an academic or theologian. His leanings, he felt, were toward the practical; he preferred to "learn by experience and from meeting people."

"The daughter of the ADRA director in Cambodia kept hounding me about coming to Cambodia," Ross remembers. Reluctant at first, he finally decided to give it a try, and on October 5, 1998, at age 24, he arrived in Cambodia. "I had no idea at all of what I was in for," he says. "I can't remember the first few months very well. I was in a daze, not really understanding anything very well."

Searching for a Way

As he began to learn, Ross was looking for ways to work for the young people of the church and community. His focus was outreach to university-age students. "The vagueness of my assignment allowed me flexibility," says Ross. "It didn't take long for me to start naively dreaming about possibilities for Cambodia."

Believing from his own experience that "education was a means to teach people about Jesus and the Christian way of living," and noticing that many young people were without jobs, direction, or know-how to get anywhere, Ross rented a small place near the University of Phnom Penh and began conducting English classes. "To my surprise, classes were soon packed and overflowing," Ross recalls. "Foreign people were a real attraction for students wanting to learn English, and it was a good way to make contact with young people. It wasn't long before there were 10 to 15 students coming to worship each Sabbath."

Believing from his own experience that "education was a means to teach people about Jesus and the Christian way of living," and noticing that many young people were without jobs, direction, or know-how to get anywhere, Ross rented a small place near the University of Phnom Penh and began conducting English classes. "To my surprise, classes were soon packed and overflowing," Ross recalls. "Foreign people were a real attraction for students wanting to learn English, and it was a good way to make contact with young people. It wasn't long before there were 10 to 15 students coming to worship each Sabbath."

The school now has more than 250 students, with volunteer teachers from around the world. A full-time director has recently been employed, and the school (whose main goal continues to be outreach) also provides employment for a number of church members. According to Ross the school is faced with both challenges and opportunities. He himself, however, has an eye to new projects.

New Directions

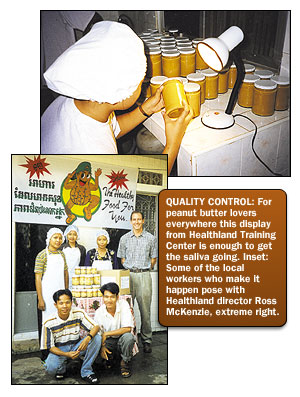

Ross could be accused of having self-interest at the center of his next proj-ect—at least in part. "When I first came here it was only a matter of a few weeks before even the thought of rice made me feel sick," Ross remembers. "I longed for something familiar—but even peanut butter cost more than US$3 for a small jar in the local supermarket." On a stipend of US$150 per month he found that beyond his budget.

A friend taught him how easy it was to make peanut butter in a kitchen blender, and he discovered that other foreigners would purchase the stuff if it could be made available at a good price. What better place to start than a peanut butter industry, he thought, with the direct personal benefit of a regular supply of peanut butter!

The students in his management class (where he first broached the idea) were skeptical. "Nobody in Cambodia eats peanut butter," they said. However, Healthland peanut butter has been selling and enjoying a growing reputation. "The students are proud of their business and work hard to realize their dream of seeing Healthland products compete in the export market," Ross says.

In addition to peanut butter Healthland now produces four varieties of tropical jams, chili paste, crushed garlic, garlic in olive oil, samlor curry paste (a traditional Khmer curry), and chili preserves. These products are sold mostly in larger food retail outlets in Phnom Penh and some other centers around Cambodia. According to Ross, "Healthland was one of three businesses chosen by the Cambodian Ministry of Commerce to send to Thailand for the Association of South-East Asian Nations product promotion meetings." Currently employing 10 students, Ross hopes the workforce might grow to 30, with expanding business.

"Our goal for Healthland," says Ross, "is not only to be a health food factory but also to develop a training program that will help develop students' abilities. Through on-the-job training, as well as classes, we hope to develop people capable of achieving useful things for their country and for their church." With most of the educated people either killed or chased out of the country during the Pol Pot regime, he says, "Cambodia desperately needs people with skills and abilities." Ross and his group have been raising funds to build a training center with accommodation for students. "Some will be employed by Healthland, which will help to pay for their accommodation and academic fees." Already several Healthland students have received scholarships to study at Mission College (the Adventist college in Thailand), and some have gained entrance into law school and into other university courses.

Thinking Big

Ross's three years in Cambodia have been filled with challenges, adventures, learning, and giving. He is excited by the things God has done in his work and sees Christianity as providing real answers to many of the problems facing the people of Cambodia.

"I love seeing people realize their talents . . . [striving] to use those talents for the benefit of others," he says. "I like seeing the church making an impact on people's lives and on the community. Cambodia desperately needs some kind of direction, and our church should be making a difference; it has a great message and a powerful God."

And while Ross has worked to share God with others, his experiences in Cambodia have also changed his relationship with God. "The problem of pain and suffering has often been one of my biggest barriers to understanding a loving God," he says. "I have seen people who vehemently object to a loving God because of the pain they see others going through. Yet I have witnessed the sufferers themselves, who have been through terrible pain—even losing their whole families and living under terrible conditions—still clinging to God without wavering, finding comfort in the arms of a loving Savior.

"Seeing hurting people find hope and be changed by God's grace has brought me closer to God."

_________________________

Nathan Brown, a freelance writer in Townsville, Australia, is currently working on a doctorate in English.

BY KIMBERLY BALDWIN RADFORD

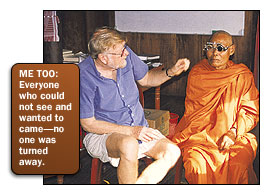

lease look at the chart; then tell me when it starts to get clearer." It's Dr. Richard Hearn's first eye exam of the morning, a typical workday. What's not so typical is his "office": a paper eye chart nailed to a tree trunk, his patient a saffron-robed Buddhist monk. A translator explains Dr. Hearn's directions in Khmer, the local language. This is optometry—Cambodian-style.

lease look at the chart; then tell me when it starts to get clearer." It's Dr. Richard Hearn's first eye exam of the morning, a typical workday. What's not so typical is his "office": a paper eye chart nailed to a tree trunk, his patient a saffron-robed Buddhist monk. A translator explains Dr. Hearn's directions in Khmer, the local language. This is optometry—Cambodian-style.

Dick and Carol Hearn first heard about the opportunity to go to Cambodia while attending the Carolina Conference camp meeting in June 1996, where it was announced that volunteer English teachers were needed to assist ADRA. Having both been teachers in the past, the Hearns were intrigued by the prospect, but their initial response was, "Where in the world is Cambodia?" That evening found them in Wal-Mart, searching for an atlas to discover Cambodia's exact location.

Something Happened; Everything Changed

While English teaching was the "hook" that God used to attract the Hearns to this small Southeast Asian country, He soon revealed that He had different plans in store. It took a land mine blowing up a bridge along the main road just a few miles from where the Hearns were to live. The situation was deemed too unstable to send in new workers.

Then another e-mail arrived: Could they still come to Cambodia but base themselves in the capital of Phnom Penh? Carol's musical skills were needed to develop a Khmer-language hymnal and to direct the music ministries at the local Seventh-day Adventist church and primary school. Dick's optometry experience could be put to good use holding mobile eye clinics in Phnom Penh and in rural provinces, where optometry services are virtually nonexistent.

Then another e-mail arrived: Could they still come to Cambodia but base themselves in the capital of Phnom Penh? Carol's musical skills were needed to develop a Khmer-language hymnal and to direct the music ministries at the local Seventh-day Adventist church and primary school. Dick's optometry experience could be put to good use holding mobile eye clinics in Phnom Penh and in rural provinces, where optometry services are virtually nonexistent.

"We are stunned," Carol responded. "I feel like I have been in training for this mission for years. There is nothing I enjoy more than working with singing groups. I would also be very interested in working on the hymnbook. What a challenge . . . I feel more and more that the Lord is leading in all of this." In January 1997 the Hearns were finally on a plane en route to hot, humid Phnom Penh.

One might expect that Dick, 72, and Carol, 68, have had years of overseas experience to give them the courage to travel far from family and the comforts of home. However, except for three weeks in Europe and several sailing trips to the Caribbean, neither had lived outside the United States. Nevertheless, the Hearns feel that their boating experience provided valuable lessons to help them adjust to life in a developing country. For eight years they lived on a small sailboat, first along the shores of freezing Lake Michigan and later off the coast of sunny Florida. As Carol explains, "We are used to roughing it. Living on a boat is not the most convenient life. We had to deal with all sorts of situations and rise to any occasion to handle the boat, the weather, and our own needs."

The adaptability required of good sailors provided an excellent foundation for Cambodia. Carol and Dick travel for many hours along bone-jarring unpaved roads to reach remote villages to hold eye clinics. Clinics are usually organized through local Adventist churches, although anyone can participate. Patients range from a provincial governor to toothless grannies; rice farmers wait in line with health workers. Buddhist monks are as welcome as Christian pastors.

With no electricity in most locales, running sophisticated diagnostic equipment is impossible. Dr. Hearn uses an old-fashioned optometrist's trial case, comprised of a briefcase with 100 sample lenses that fit into a special frame that the patient wears, allowing him to conduct a rudimentary eye exam. After Dick determines a patient's prescription, Carol searches through hundreds of presorted eyeglasses to find the closest match.

One particular patient stands out in Dr. Hearn's mind. After more than 100 villagers had been seen on a hot, tiring day, an older woman sat down to be examined. No matter what lens Dick placed in front of either eye, the woman replied, "Not clear." This continued for many minutes until Dick finally decided to put an end to what seemed to have become a game. Selecting the thickest lens in his kit, he inserted it into the frame. "It's clear!" the woman shouted. Amazingly, Carol had a pair of glasses to match such a strong prescription. A large smile wreathed the woman's wrinkled face as she compared the scene through her "old eyes" and then with her "new" glasses.

So They Might Sing

When not helping Dick with eye clinics, Carol is busy with her own music ministry. Trying to compile a hymnal when one can neither read nor speak the language is a daunting task. Carol and her Cambodian assistants, however, have developed a 500-page hymnal comprised of traditional Cambodian songs rewritten with Christian words, as well as a few translated Western hymns. Because illiteracy is a problem for many people, illustrations have been added to make the book interesting for children and those who can't read. Produced by a local artist, the drawings depict people with Khmer features and Cambodian-style clothing in scenes of well-known Bible stories.

The Hearns' original plan was to stay in Cambodia for two years—a reasonable time to allow for the completion of the hymnal and not too long to be away from family and friends. In March 1997 political unrest became evident when violence erupted during a labor-related protest rally in the capital. Four hand grenades were thrown into the crowd, killing 16 people.

The Hearns' original plan was to stay in Cambodia for two years—a reasonable time to allow for the completion of the hymnal and not too long to be away from family and friends. In March 1997 political unrest became evident when violence erupted during a labor-related protest rally in the capital. Four hand grenades were thrown into the crowd, killing 16 people.

For several tense months the Hearns witnessed an increased military presence in Phnom Penh. The situation became untenable. Although relatively close to Phnom Penh's international airport, the Hearns had to encounter hostile soldiers, fires, and looting that blocked the only road between the church and a possible flight to safety.

After three trips to the now-gutted airport the Hearns were finally able to leave on an evacuation flight to Thailand on July 9. Hoping to wait out further political unrest, they eventually continued on to the United States as the situation in Phnom Penh remained unstable.

Unfinished Business

Dick and Carol returned to their loved ones with mixed feelings. Cambodia was no longer just a tiny country in a world atlas. Left behind were friends and a congregation that they'd grown to love. Long hours had been put into working on the hymnal and starting the mobile eye clinics. Now that they'd witnessed the desperate needs firsthand, they were not content to leave their ministry behind.

December 30, 1997, almost exactly one year from their initial arrival in Phnom Penh, Dick and Carol greeted the upcoming new year by boarding a flight to Cambodia for the second time. Not everyone understood why they would return to a country that seemed violent and unpredictable, but the Hearns had no doubts. "Jesus left a place much better than America and went to a country—a world—that was hot and dusty and dangerous," Carol explained, "and we just felt like we needed to come back and finish the work that He had sent us to do."

December 30, 1997, almost exactly one year from their initial arrival in Phnom Penh, Dick and Carol greeted the upcoming new year by boarding a flight to Cambodia for the second time. Not everyone understood why they would return to a country that seemed violent and unpredictable, but the Hearns had no doubts. "Jesus left a place much better than America and went to a country—a world—that was hot and dusty and dangerous," Carol explained, "and we just felt like we needed to come back and finish the work that He had sent us to do."

Postscript: Since the July 1998 elections and the disbanding of the Khmer Rouge, Cambodia's political situation seems to have stabilized. Carol and Dick Hearn left Phnom Penh at the end of September 1998, after distributing more than 4,000 pairs of donated eyeglasses to people in 14 of Cambodia's 23 provinces and municipalities. Eye clinics continue with staff trained by Dr. Hearn during his stay; an additional 500 glasses have been dispensed in the past year. In January 1999, 4,000 hymnals were printed that are being used in more than 25 Adventist churches and worship groups throughout Cambodia.

_________________________

Kimberly Baldwin Radford and her husband, Colin, lived in Cambodia from 1994-1998. They now reside in Toamasina, Madagascar.