Millerite Adventists,

including the seventh-day variety, drew upon more than 300 years of Protestant

historicist interpretation in identifying the first two beasts of Revelation

13 with pagan and papal Rome. Protestants from Martin Luther and the English

Reformers through seventeenth-century American Puritan writers such as John

Cotton, John Eliot, and Cotton Mather had laid the groundwork. A long interpretative

tradition identified a historical succession in the prophetic symbolism of John's

"beastly powers" by which the military tyranny of imperial Rome became

the political and ecclesiastical tyranny of the medieval and Reformation-era

Papacy.

Cross-referencing

the book of Revelation with the Old Testament prophecies of Daniel had led Protestant

authors to identify the predicted reign of the papal "second beast"

with a period of 1260 years. Millerite Adventists, along with other Evangelicals,

had concluded that this 1260-year period had ended in 1798, when Napoleon Bonaparte's

armies invaded the Papal States and made Pius VI a prisoner, inflicting the

"deadly wound" predicted by the apostle. The logic of their approach

now dictated that they look for a contemporary political power, symbolized by

the third or "lamblike beast" of Revelation 13, that would help the

wounded papal authority reestablish its worldwide hegemony. The new political

power would persecute God's true saints who "keep the commandments of God

and hold the testimony of Jesus" (Rev. 12:17),* especially including the

seventh-day Sabbath.

By so doing, that

political power would demonstrate its predicted true character: it would "speak

like a dragon," (Rev. 13:11) and cause "all, both small and great,

both rich and poor, both free and slave" to be "marked"

indicating submission to papal authority (verse 16). Even more ominously, it

would exercise almost total economic control: "No one can buy or sell who

does not have the mark, that is, the name of the beast or the number of its

name" (verse 17).

The "seventh-day"

Adventists weren't the first to identify America with the "two-horned beast"

of Revelation 13. Ebenezer Frothingham, a leading minister of the eighteenth-century

Great Awakening, had made the connection explicit more than a century earlier.5

The contribution of the Review authors and editors was to identify the

United States as the third beast because it mandated submission to papal

authority, tolerated (and even embraced) a culture both "free and slave,"

and dominated an economic system built on these evils. Slavery wasn't only morally

reprehensible, and thus a "foul blot"6 on the national character of

the United States: it also identified the United States as the predicted oppressive

power that would exercise control immediately before the second coming of Jesus.

Indicting the

Nation

Like all detailed prophetic interpretation, this is complicated stuff. But for

the editors who assembled the Advent Review and Sabbath Herald from 1853

to 1861 it wasn't simply speculative inquiry. They were as convinced of their

identification of the United States as the predicted persecuting power as they

were of the necessity of keeping the seventh-day Sabbath or of the nearness

of the Second Coming.7 It was the apparent contradiction between appearance

and character that fascinated them: the third beast appeared "lamblike"

and mild, but acted like a dragon. It was only a short step to an identification

with a young nation that purported to embrace the republican and "mild"

principles of toleration and freedom of conscience, but was already enslaving

more than three and a half million of its own inhabitants.

So it was that

a succession of Review authors and editors during this eight-year span

lined up to indict the United States for failing to live up to its first principles.

According to E. R. Seaman the Fugitive Slave Law was "the foulest stain

that ever blotted the history of any nation, especially one whose professions

are entirely of an opposite character."8 A year later J. N. Andrews would

write, "If 'all men are born free and equal,' why then does this power

hold three millions of human beings in the bondage of slavery? Why is it that

the Negro race is reduced to rank of chattels personal, and bought and sold

like brute beasts?"9 James White expected little in the way of reformation:

"How much of the prophecy relating the two-horned beast remains to be fulfilled?

It has arisen with its lamb-like horns. Its dragon voice has been heard speaking

forth sentiments of oppression, the reverse of its lamb-like profession of freedom

and equal rights among all men. We believe his voice is yet to be heard denying

the true Christian his right of conscience in the service of God."10

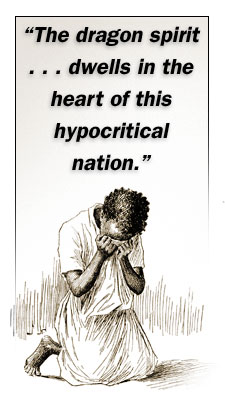

Resident editor

Uriah Smith pressed the indictment even more pointedly:

"Says the

Declaration of Independence, 'We hold these truths to be self-evident; that

all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain

unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness;'

and yet the same government that utters this sentiment, in the very face of

this declaration, will hold in abject servitude over 3,200,000 of human beings,

rob them of those rights with which they acknowledge that all men are endowed

by their Creator, and write out a base denial of all their fair professions

in characters of blood. In the institution of slavery is more especially manifested,

thus far, the dragon spirit that dwells in the heart of this hypocritical nation."11

"Says the

Declaration of Independence, 'We hold these truths to be self-evident; that

all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain

unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness;'

and yet the same government that utters this sentiment, in the very face of

this declaration, will hold in abject servitude over 3,200,000 of human beings,

rob them of those rights with which they acknowledge that all men are endowed

by their Creator, and write out a base denial of all their fair professions

in characters of blood. In the institution of slavery is more especially manifested,

thus far, the dragon spirit that dwells in the heart of this hypocritical nation."11

Proslavery ministers

also came in for thinly-disguised scorn in the pages of the Review. A

reprinted article from The Wesleyan confidently asserted, "The

Bible no where lends its high and solemn sanction to any form of moral evil."12

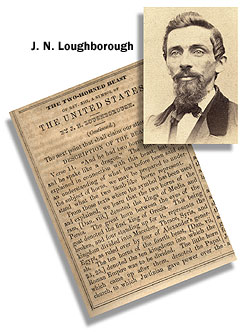

John Loughborough

argued that proslavery clergy ought at least to apply Scripture consistently:

"The ministry

of these churches South argue that there is no moral wrong in slavery; for it

is a patriarchal institution, and was sanctioned by the Lord in the ceremonial

law. If they contend that it is morally right to hold slaves now because they

were held in patriarchal times, then it must be morally right to use them as

they were used then. Then every one could go free at the jubilee every

seventh year, unless he loved his master and wanted to abide with him. Let those

who contend for patriarchal slavery here, carry it out fully and give the slaves

one jubilee, and what would be the result?"13

The

Breadth of Evil

Articles and editorials appearing in the magazine also castigated specific institutions

that appeared to be tolerating the fundamental wrong that Review writers

believed slavery to be. The Methodist Episcopal Church and the American Tract

Society, both of which endured protracted debates about slavery, were frequently

cited for a lack of moral courage. John Wesley's description of slavery as "the

sum of all villainies" was regularly quoted,14 and significant space was

given to reprints from other journals that were critical of the Methodist equivocation

regarding slavery.15

A reprinted article

also scorned the American Tract Society, one of the most influential of the

interdenominational movements of the era, for its unwillingness to denounce

slavery:

"A religion

that dares not rebuke stealing, adultery, and blasphemy, under the general name

of slavery, is a whited sepulchre, and is in alliance with the bitterest foes

of Christ. If the American Tract Society, through a squeamish conservatism,

a most unmartyr-like fear and liberalism has been betrayed into this sin, let

it repent, and bring forth works meet for repentance."16

The drumbeat of

Adventist opposition to slavery only increased as the 1850s progressed. The

Fugitive Slave Law was routinely lambasted, both for its inherent moral depravity

and for the evidence it provided of how the proslavery forces were controlling

the national political agenda.17 Lengthy accounts of the capture of fugitive

slaves in Northern cities were printed, and their captors were regularly denounced.

Review

authors and writers routinely scorned the celebrated "national reconciliations"

of the pre-Civil War era-the Missouri Compromise of 1820 and the Compromise

of 1850-as Northern acquiescence to Southern political domination.18 The costs

of slavery in human and economic resources were deplored as well. Review

editors read the recent his-tory of their country as the outworking of slave-holding

power upon the national government:

"I hesitate

not to say that this government has been so administered, for the last quarter

of a century, as to be destructive of the lives, the liberties and the happiness

of a portion of the people; in short, it has become destructive of the very

objects for which it was established. Its influence and its powers have been

exerted to extend the most barbarous system of human bondage known to mankind.

Three distinct and separate wars have been waged to uphold and maintain the

system of American slavery. More than three hundred millions of dollars have

been drawn from the pockets of our laboring people, and paid out by government

for that purpose, and more than five hundred thousand human victims have been

sent to premature graves to uphold and maintain the interests of an institution

which the present administration and its supporters are seeking to extend and

eternise."19

"I hesitate

not to say that this government has been so administered, for the last quarter

of a century, as to be destructive of the lives, the liberties and the happiness

of a portion of the people; in short, it has become destructive of the very

objects for which it was established. Its influence and its powers have been

exerted to extend the most barbarous system of human bondage known to mankind.

Three distinct and separate wars have been waged to uphold and maintain the

system of American slavery. More than three hundred millions of dollars have

been drawn from the pockets of our laboring people, and paid out by government

for that purpose, and more than five hundred thousand human victims have been

sent to premature graves to uphold and maintain the interests of an institution

which the present administration and its supporters are seeking to extend and

eternise."19

Even presidents were criticized for dillydallying about slavery. "At this

critical moment [March 28, 1854, during the presidency of New Hampshire native

Franklin Pierce] the astounding proposition comes from the citizen who is now

president," a reprinted piece opined, "to repeal the statute which

secures the immeasurable blessings of freedom to Nebraska, and to establish

therein the dire institution of African Slavery."20 A reprint from the

London Freeman, general paper of English Baptists, criticized the 1856

election of James Buchanan and tweaked freedom-loving Americans at the same

time:

"The election

of Mr. Buchanan was a great triumph of the worst of causes; of slavery and slaveholders

over Christianity and Christian churches; and it was gained by the defection

of the great Quaker State, Pennsylvania, from the principles of its founder!

America is the most degraded, at pres-ent, morally and religiously, of all free

and Protestant countries. It is the reproach of evangelical christendom. Her

slaveholders defy both God and man, and the freemen of the free states sacrifice

their own political freedom and the personal rights of the negro, to a low and

noisy political party! The United States are to us a greater grief than heathendom

and popery, for the names of Christianity and Protestantism, of civil and religious

liberty, are blasphemed through them. Oh, that the free states may burst their

fetters, get rid of the accursed thing, and join the mother country in heading

the march of Christianity and civilization!"21

The Supreme Court's

Dred Scott decision (which allowed for the re-enslavement of a previously

freed slave) was denounced by Uriah Smith22 and again in a lengthy extract of

a speech by Abraham Lincoln from the celebrated Lincoln-Douglas debates of the

1858 Illinois senatorial campaign. The increasing agitations and violence in

Kansas were also duly noted. While the Review editors were clearly favorable

to the antislavery forces attempting to settle in Kansas, they printed an article

that deplored the northern Evangelical ministers who endorsed violence as a

solution to the territory's crisis:

"Are these

men following Jesus? Are they harnessing themselves and followers with gospel

weapons? Are they exhibiting implicit confidence in the perfect law of God?

Do they acknowledge that there is but one Lawgiver for the Christian? Do they

hear Paul say, 'The weapons of our warfare are not carnal, but mighty through

God, to the pulling down of strongholds?' 2 Cor. 10:4. Are they finally heeding

the scriptures that they professedly teach?"23

Activism,

Not Politics

In light of what today would be regarded as the increasing "politicization"

of the Review's content through the 1850s, it is remarkable how firmly

most Review authors and editors avoided direct political involvement.

During the Buchanan-Fremont presidential contest of 1856, Uriah Smith pronounced

both the Democratic and Republican candidates unsuitable because they weren't

committed to the eradication of slavery. Just one week before the November election,

corresponding editor R. F. Cotrell reiterated the futility of voting:

"But you

can vote against slavery, says one. Very well; supposing I do, what will be

the effect? In the last great persecution, which is just before us, the decrees

of the image will be against the 'bond' as well as the free. Bondmen will exist

then till the last-till God interposes to deliver His saints, whether bond or

free. My vote then cannot free the slaves; and all apparent progress towards

emancipation will only exasperate their masters, and cause an aggravation of

those evils it was intended to cure. I cannot, therefore, vote against slavery;

neither can I vote for it."24

Not all Review

readers appreciated the non-political approach of the editorial team. Because

the magazine also functioned as a kind of billboard for isolated Seventh-day

Adventists, strongly-worded letters to the editor were a regular feature. Anson

Byington, a New York relative of the man who would become the first president

of the denomination when it officially organized in 1863, complained that the

Review was abandoning the moral high ground by not advocating more direct

action:

"Bro. Smith:

I have taken the Review some six or seven years and have been much edified

with its contents. Having been engaged for the last twenty-five years in the

antislavery cause, I have regarded the Review as an auxiliary until the

last two or three years, in which it has failed to aid the cause of abolition.

And as I want my money for abolition purposes, I must discontinue the paper

when the three dollars herein enclosed are expended.

"I dare not

tell the slave that he can afford to be contented in his bondage until the Saviour

comes however near we may believe his coming. Surely the editor of the Review

could not afford to go without his breakfast till then. If it was our duty to

remember those in bonds as bound with them eighteen hundred years ago, it must

be our duty still. 'When saw we thee hungry or athirst, sick or in prison, and

did not minister unto thee.'"25

"I dare not

tell the slave that he can afford to be contented in his bondage until the Saviour

comes however near we may believe his coming. Surely the editor of the Review

could not afford to go without his breakfast till then. If it was our duty to

remember those in bonds as bound with them eighteen hundred years ago, it must

be our duty still. 'When saw we thee hungry or athirst, sick or in prison, and

did not minister unto thee.'"25

Byington lamented,

"Alas! we saw the slave in prison, but on reading the prophecy that there

will be bondmen as well as freemen at Christ's coming, we have excused ourselves

from any efforts for his emancipation."26

The editors clearly

felt the need to defend themselves from the implication that they weren't completely

serious about their opposition to slavery. With more than a touch of indignation,

they answered Byington by stressing their inability to do anything practical

about the social evil:

"Our feelings

in regard to slavery could hardly be mistaken by any who are acquainted with

our position on the law of God, the foundation of all reform, the radical stand

point against every evil. Slavery as a sin we have never ceased to abhor; its

ravages we have never ceased to deprecate; with the victims locked in its foul

embrace, we have not ceased to sympathize. But what is to be done? The tyranny

of oppression secludes them from our reach."27

The Review

editors must have realized that such protests of helplessness rang hollow in

a magazine that had frequently celebrated the courageous acts of those resisting

the Fugitive Slave Law and had condemned institutions that refused to declare

themselves forthrightly against slavery. Nonetheless, they reaffirmed their

belief that political activity was shortsighted and distracting in light of

the imminent end of the world predicted in Bible prophecy. Then, and only then,

would slaves experience the emancipation that Byington and other more radical

Adventists sought to achieve for them now:

"In saying

this, we do not tell the slave that he can afford to be content in slavery,

nor that he should not escape from it whenever he can, nor that all good men

should not aid him to the extent of their power, nor that this great evil should

not be resisted by any and all means which afford any hope of success. All this

should be done. And we rejoice when we hear of one of that suffering race escaping

beyond the jurisdiction of this dragon-hearted power. But we would not hold

out to him a false ground of expectation. We would point him to the coming of

the Messiah as his true hope. We would proclaim to him the near approach of

the great Jubilee, and bid him not despair under his accumulated woes."28

No Golden Millennium

With a fundamentally pessimistic view about human progress and the uplift of

the race that grew out of their eschatological vision, the "seventh-day"

Adventists of the 1850s set their faces like flint against the prevailing optimism

of their Evangelical subculture about the future of the American nation. Their

repeated tirades against American iniquities made apparent that they shared

no optimism that a "golden" millennium might begin in America and

move eastward to bless the Old World.29 Not only was the nation not, as some

Protestant clergy were proclaiming from influential pulpits, "destined

to lead the way in the moral and political emancipation of the world,"30

but the United States was prophesied to play a profoundly malignant role in

the world crisis that preceded the Second Advent.

When the Civil

War commenced in April 1861, the Review saw little reason to alter its

pessimistic assessment of America's future. As Southern states seceded from

the Union and prepared for war, the editors denounced the pro-slavery sentiments

of "traitors and thieves"31 even as they lamented the inevitability

of the coming conflict.

Four months after

the shelling of Fort Sumter, Uriah Smith wrote an editorial introduction to

a reprinted article from the abolitionist journal American Missionary

entitled "The National Sin." While the article itself at least implied

that America, purged of the evil of slavery, might again become the object of

God's special affection, Smith offered no such positive prediction. His editorial

note is an apt summary of the consistent position that he and his Review

colleagues had articulated during the previous eight years.

"From the

following article it appears that we are not alone in our views of the hypocritical

and wicked character of this nation. . . . Though in appearance it is innocent

and 'lamb-like,' it 'speaks like a dragon.' Well does the writer remark that

the 'Almighty has a controversy with this nation;' and not only with this nation,

we may add, but he has a controversy with all nations [Jer. 25:31], upon which

he is evidently now about entering [Luke 21:25, 26]; and of the cup of God's

fury from which all nations will be required to drink [Jer. 25:15] we believe

the dregs will be administered to our own [Jer. 25:26; Ps. 125:8]; for the guilt

of any people is in proportion to the strength and brightness of the light which

they reject; and how much light has been rejected by this government may be

learned from the fact that a black and revolting iniquity which all other nations

pretending to any degree of civilization have repudiated, and from which they

are hastening to cleanse their hands, is still hugged by our own with a sottish

tenacity, the people in one portion of the country blasphemously endeavoring

to defend it by the Bible, and too many of the rest conniving at both its existence

and its arrogant claims."32

As the Review's

editors saw it, the Almighty's controversy with the nation wouldn't end with

either a blood atonement offered from the veins of its young men or with a grant

of divine forgiveness. Only the second advent of Jesus, whose announced mission

was "to proclaim release to the captives" and "to let the oppressed

go free" (Luke 4:18) would finally erase all distinctions between "slave"

and "free." Their passionate opposition to the moral wrong of slavery

was part and parcel of their Adventism, and an illustration of the truth that

persons completely committed to the reality of God's new world often make the

best citizens of this one.

_________________________

*Bible texts in this article are from the New Revised Standard Version.

1Uriah Smith,

"The Warning Voice of Time and Prophecy," Advent Review and Sabbath

Herald, June 23, 1853.

2Oliver Jacques, "Driven by a Dream," Adventist Review, May

24, 2001.

3Ibid.

4The journal now known as the Adventist Review.

5Ebenezer Frothingham, "The Articles of the Separate Churches," in

The Great Awakening: Documents Illustrating the Crisis and Its Consequences,

ed. Alan Heimert and Perry Miller (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill Co., 1967), p.

452.

6James White, "True Reforms and Reformers," Advent Review and Sabbath

Herald, June 26, 1856.

7A new archival resource, Words of the Pioneers, produced by the Adventist Pioneer

Library, allows a full-text search of all content in the Advent Review and

Sabbath Herald in this period.

8E. R. Seaman, "The Days of Noah and the Sons of Man," Advent Review

and Sabbath Herald, June 13, 1854.

9J. N. Andrews, "The Three Angels of Rev. XIV, 6-12," Advent Review

and Sabbath Herald, Apr. 3, 1855.

10James White, "Revelation Twelve," Advent Review and Sabbath Herald,

Jan. 8, 1857.

11Uriah Smith, "The Two-Horned Beast-Rev. XIII," Advent Review

and Sabbath Herald, Mar. 19, 1857.

12"The Decalogue," Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, Dec. 13,

1853.

13J. N. Loughborough, "The Two-Horned Beast of Rev. XIII, a Symbol of the

United States," Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, July 2, 1857.

14Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, Mar. 6, 1855; "Methodism and

Slavery," Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, May 27, 1858.

15"Methodism and Slavery," Advent Review and Sabbath Herald,

May 27, 1858.

16In Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, May 21, 1857.

17"The Nebraska Bill," Foreign News, Advent Review and Sabbath

Herald, Mar. 7, 1854; J. N. Loughborough, "The Two-Horned Beast,"

Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, Mar. 21, 1854.

18Loughborough, "The Two-Horned Beast of Rev. XIII," Advent Review

and Sabbath Herald, July 9, 1857.

19J. R. Giddings, reprinted in Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, Feb.

5, 1857.

20New York Tribune, Feb. 18, 1854, in Loughborough, "The Two-Horned Beast,"

Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, Mar. 28, 1854.

21"What Is Said of Us," Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, Apr.

8, 1858.

22Smith, "The Two-Horned Beast-Rev. XIII," Advent Review and Sabbath

Herald, Mar. 19, 1857.

23E. Everts, "Follow Me," Advent Review and Sabbath Herald,

Aug, 14, 1856.

24R. F. Cottrell, "How Shall I Vote," Advent Review and Sabbath

Herald, Oct. 30, 1856.

25Anson Byington in Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, Mar. 10, 1859.

26Ibid.

27Editorial note, Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, Mar. 10, 1859.

28Ibid.

29Jonathan Edwards, "The Latter-Day Glory Is Probably to Begin in America,"

in God's New Israel: Religious Interpretations of American Destiny, ed.

Conrad Cherry (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998), p. 55.

30Lyman Beecher, "A Plea for the West," in God's New Israel,

p. 123.

31William S. Foote, "Notes on Men and Things," Advent Review and

Sabbath Herald, Apr. 16, 1861.

32Smith, "The National Sin," Advent Review and Sabbath Herald,

Aug. 20, 1861.

_________________________

Bill Knott is an associate editor of the Adventist Review.