It is midnight—somewhere on a road. An eerie silence seems to be palpable. The family should have long since come to rest. Yet the completely unfathomable happens. God attacks, and Moses’ life is at risk.

This utterly mysterious event is described in Exodus 4:24-26: “At a lodging place on the way the Lord met him and sought to put him to death. Then Zipporah took a flint and cut off her son’s foreskin and touched Moses’ feet with it and said, ‘Surely you are a bridegroom of blood to me!’ So he let him alone. It was then that she said, ‘A bridegroom of blood,’ because of the circumcision” (ESV).1

Nothing in the text prepares us for what is happening here. After 40 years Moses seemed to have finally escaped his assassins, “for all the men who were seeking your life are dead,” so at least God assured him (Ex. 4:19; cf. Ex. 2:15). However, this very same God was now “seeking his life,” although He had just commissioned him to go to Egypt. Is God capricious? Why did God want to kill Moses? And why did Zipporah’s deed avert the impending disaster?

Following his divine call, Moses said goodbye to Jethro (Ex. 4:18), and, together with his wife and their two sons, set out for Egypt (verse 20). They came to “a lodging place,” which was probably an overnight stay in the open, for Zipporah quickly had a sharp stone at her fingertips. The accompanying donkey echoes other stories that exhibit the “deadly donkey motif”: Abraham and Isaac (Gen. 22:3, 5), or Joseph’s brothers, who at a lodging place (same word as in Ex. 4:24) were terrified when they discovered the money as they wanted to feed their donkeys (Gen. 42:26-28; 43:21). Sometime in the future Balaam, riding “by God’s order” on a female donkey to Moab, will be stopped by the angel of Yahweh who is ready to kill him (Num. 22).

The Hebrew explicitly says that Yahweh wanted to kill Moses. For the first translators this was too scandalous. Instead of “Yahweh,” they read “angel of the Lord” (Greek Septuagint), “messenger of Yahweh” (Aramaic Targumim), or even “Mastema,” a chief demon or Satan (Book of Jubilees). Such renditions intended to take the edge off the text.

The problems of the text reside in its apparent ambiguity. In the Hebrew original, subject and object are not clearly spelled out (cf. NKJV). Whom did Yahweh want to kill, Moses or his son? Whose feet were touched by the severed foreskin? Who was called “bridegroom of blood”? Did Zipporah save Moses because he was uncircumcised or because one of their sons was uncircumcised? Or did she save Moses’ son?

A close reading provides helpful circumstantial evidence.

Evidence 1—circumcision: Zipporah “cut off her son’s foreskin” (Ex. 4:25). Even if Moses is not mentioned by name in verse 24, the object of Yahweh’s attack should be Moses and not one of his sons, since Moses was also the main character in the previous section (verses 18-23).

Evidence 2—“bridegroom of blood”: This expression indicates that Moses’ feet had been touched, for the Hebrew word “bridegroom” does not refer to blood relatives but to a husband (Isa. 62:5)

or other affinal relatives (Judges 19:5;

2 Kings 8:27).

Evidence 3—blood on Moses: Zipporah touched Moses’ genitals (euphemistically called “feet,” [see Judges 3:24;

1 Sam. 24:3; 2 Kings 18:27]) with her son’s foreskin. This symbolic act and the particular phrase she used (“bridegroom of blood”) conferred some kind of protection upon Moses. The verb seems to foreshadow the final plague in Egypt and the concurrent rescue of Israel’s firstborn. “Touching” (same word as in Ex. 4:25) the doorposts with the blood of the Passover sacrifice saved the firstborn from Yahweh (Ex. 12:13, 22, 23). Similarly, when Zipporah touched Moses with blood, it saved him from Yahweh’s judgment. This illustrates the vitally important role of blood (Ex. 24:8; Lev. 17:11). The connection between the assassination attempt of Moses and the tenth plague is not accidental, considering that just before the nighttime incident we find a divine pronouncement informing Moses that a confrontation with Pharaoh that will culminate in God killing Pharaoh’s firstborn son (Ex. 4:21-23) awaits him.

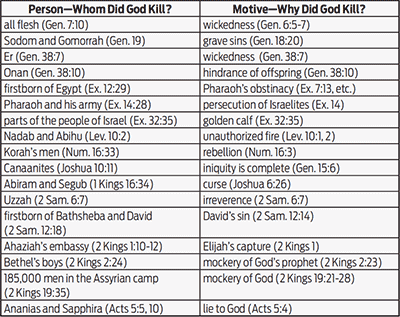

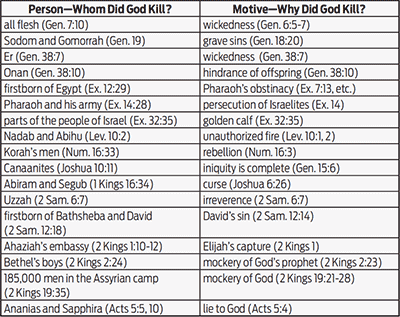

The question of motive is most important. Let’s start with God’s actions. There are a number of biblical instances in which God is said to have killed people. When and why does He kill?

The table below illustrates the seriousness of sin. It is then all the more surprising that God sought Moses to kill him. This must have been because of a very serious offense. So what was going on?

Evidence 4—a “sharp stone” that “cut”: It is important to note that the Hebrew verb karat, “to cut,” is used in Exodus 4:25 to describe the act of circumcision. Elsewhere in the Old Testament the Hebrew term mul is used (it also appears in verse 26 in a nominal form). The verb “cut” is employed here because it is typically used in expressions describing the “making” of a covenant. Its use here signifies that a covenant relationship is involved. The act of circumcision pertains to the status of Moses’ family in relation to the divine covenant with His people. Circumcision, the visible covenant sign between God and His people, was so significant that a person who actually belonged to Israel but would not get circumcised had to be cut off from God’s people (Gen. 17:14).

There is also a connection between Moses’ return to Egypt and Israel’s entry into Canaan (Joshua 5:2, 3). Only these two incidents describe a circumcision with flint knives. The younger generation was still uncircumcised, although their fathers themselves had been circumcised and knew about its commandment (Lev. 12:3). Before the new generation could begin the divinely ordained conquest of Canaan, they needed to enter into the divine covenant by circumcision. Similarly, Moses needed to circumcise his son and exhibit the covenant sign in his family before he would lead Israel out of Egypt. Touching Moses’ genitals with circumcision blood seems then to be a symbol for Moses’ reinstatement into God’s covenant.

Thus his son’s circumcision saved Moses’ life.2

Evidence 5—Zipporah: Zipporah was the only person who, in the right moment, could perform the circumcision. It is absolutely unique in the Bible that a woman performed the ritual of circumcision. And so after his mother, Miriam, and Pharaoh’s daughter, it was once more a woman who saved Moses’ life. Evidently Moses was paralyzed by the divine threat so that he could not perform the circumcision himself. Only Zipporah was active. Showing her presence of mind, she assumed the role of the mediator between Yahweh and Moses, and her action saved the day. Her deed provides the final evidence, for how did she realize what needed to be done? Zipporah must have known why God acted so strangely and that He was aware of their family circumcision problem. She likely was involved in the neglect to circumcise her son, if she was not the cause herself.3

Undoubtedly, if God really would have wanted to kill Moses, He would have done so. Instead the text mentions that Yahweh sought to kill him. What does this seeking mean? Certainly not that God’s first attempt was foiled. Rather God’s seeking to kill Moses alleviates the divine visitation. God opened a window of opportunity in which humans could act. “It is therefore not to be understood that Zipporah thwarts a single-minded divine intention for death; rather, she moves into the temporal spaces allowed by God’s seeking.”4

God’s intention was to teach a lesson. In this regard Moses’ experience resembles Jacob’s wrestling match at the Jabbok. There are a number of verbal and motif parallels that are hardly incidental: (1) “meet” (in the Pentateuch only in Gen. 32:17; 33:8; Ex. 4:24, 27); (2) “touch” (Gen. 32:25, 32; Ex. 4:25); (3) both happened at night on the way “home”; and (4) subsequently the main character kissed his brother who came to meet him (Gen. 33:4; Ex. 4:27). When God stood in Moses’ way, He apparently wanted to send him off, like Jacob, with a blessing.

The scenario can be envisioned as follows: Before Moses could enter the life-or-death struggle in Egypt, God needed to confront him, for Moses and Zipporah had not committed themselves totally to the covenant with God. They had not circumcised their son. Only after Moses had faced God Himself and the situation was rectified could he face any enemy, including Pharaoh himself.

This incident is an important divine illustration teaching us the seriousness of getting involved with the living God. We are called to dedicate ourselves totally and wholeheartedly to God in every aspect of life. God would do anything for the sake of Moses, even if it involved putting Moses’ life at risk. God did win—and so did Moses. Therefore, the final verdict about God should be “not guilty.”