Illustration by Steve Creitz

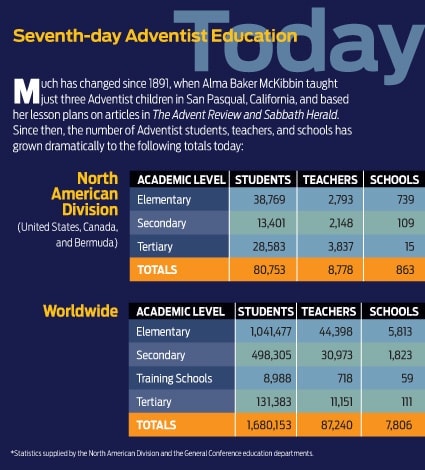

In the 1890s Ellen White wrote repeatedly from Australia to the believers in the United States, calling for Christian education at the elementary school level.

Typical of her counsel is this passage published in 1901: “Wherever there are a few Sabbathkeepers, the parents should unite in providing a place for a day school where their children and youth can be instructed. They should employ a Christian teacher, who, as a consecrated missionary, shall educate the children in such a way as to lead them to become missionaries. Let teachers be employed who will give a thorough education in the common branches, the Bible being made the foundation and the life of all study” (Testimonies for the Church, vol. 6, p. 198).

But our colleges, though we were proud of them, were always in debt. Rousing appeals were made every year at camp meeting to raise enough money to be able to start the next year in the black. Members must’ve wondered, How could God ask us to start hundreds more money-consuming schools?

But our colleges, though we were proud of them, were always in debt. Rousing appeals were made every year at camp meeting to raise enough money to be able to start the next year in the black. Members must’ve wondered, How could God ask us to start hundreds more money-consuming schools?

Arguments were raised: “If we have schools, there will be no money for missions.” “Public schools are good enough! They educated me; I wasn’t harmed any.”

Churches discussed the counsel, conferences debated the counsel, but the answer was always the same: “We don’t see our way clear at this time.”

Two other questions perplexed local churches: Where could schools be held? And who would teach?

Most churches at that time were one-room affairs; no nice Sabbath school classrooms or fellowship halls such as we have today. And as for teachers, Adventists first turned to church members already teaching in public schools. They reminded them of the counsels coming from Australia, and teachers would say, “Yes, we’ve read those counsels, and we agree. We know how to teach public school, but Ellen White is calling for something different, and we don’t know how to do it. We were never taught to make the Bible and the book of nature the basis of education. And we only know how to teach the mind, we have no idea how to make education the ‘harmonious development of the physical, the mental, and the spiritual, powers’ [Education, p. 13].”

A Soul Conflicted

Such were the troubling thoughts that tormented the mind of Alma Baker McKibbin in 1897 when some parents at the small church in San Pasqual, California, came to ask her to teach their children.

McKibbin was just then recovering from a long, debilitating illness herself. She had recently laid her only child and her husband in the grave.

But McKibbin said yes, and began to homeschool three Adventist children. She bravely made lesson plans without books, rereading articles in The Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, and trying her best to follow the counsel.

But McKibbin said yes, and began to homeschool three Adventist children. She bravely made lesson plans without books, rereading articles in The Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, and trying her best to follow the counsel.

The whole church in San Pasqual began to talk about starting an official church school. McKibbin read the “handwriting on the wall” and ran. Teaching three beginners was one thing, but all eight grades? No way!

McKibbin left San Pasqual and found a job working in a kitchen in Los Angeles. A little like Jonah, she felt safe when nobody in the large Los Angeles church seemed to notice her.

You can run from God’s call, but you can’t hide. One Sabbath in the fall of 1898 the visiting preacher was George Snider, a classmate of McKibbin’s from Healdsburg College. He recognized the “fugitive” and sent her a note from the platform. “The members at Centralia need a church school teacher. Please remain after the service; I want to talk to you about it.”

McKibbin slipped out during the closing hymn, secure in the thought that no one there knew where she lived. The next Sabbath she sat in the very back seat, but Snider was there again, and again he sent her a note. This time she left before the closing hymn.

But Snider was determined, and had, unbeknown to Alma, sent an usher to follow her home and take note of her address.

Sunday evening there was a knock on her door, and Snider, along with a delegation from the Centralia church, appeared. “We’re glad we found you!” Snider exclaimed.

“I’m sorry; it won’t do any good,” McKibbin replied. “I can’t teach a church school. I would if I could.”

Then Snider asked, “Has God ever asked you to teach church school?” After a pause he continued, “I’ll come back in the morning for your answer.”

As he left she replied, “Please don’t come back; you have my answer.”

All night long McKibbin fought a spiritual battle, and just before morning she prayed, “Lord, I’m willing to go and fail.”

Beginning at Square One

The Centralia school was located near the present-day Knott’s Berry Farm and Disneyland in Orange County, California. In those days the area was all farmland, or I should say it had been farmland. A four-year drought had left the farmers almost destitute.

The school consisted of a little addition constructed onto the back of the church with used lumber. It was made of “board and batten” construction—without the battens. That meant that every 10 inches or so a quarter-inch crack made it just perfect for the Santa Ana winds off the Mojave Desert to blow in bucketfuls of dust. Two narrow windows provided so little light that the door had to be left open in order to add extra illumination needed to read.

The school consisted of a little addition constructed onto the back of the church with used lumber. It was made of “board and batten” construction—without the battens. That meant that every 10 inches or so a quarter-inch crack made it just perfect for the Santa Ana winds off the Mojave Desert to blow in bucketfuls of dust. Two narrow windows provided so little light that the door had to be left open in order to add extra illumination needed to read.

Ten double seats, salvaged from a public school trash heap, comprised the students’ desks. Someone found a table with only three legs. A strategically placed wooden box doubled as both the fourth leg and a seat for the teacher’s desk. A 12-inch-wide board placed along the top of one wall was painted black and served as a blackboard. An old, smoky stove heated the “air-conditioned” room.

School supplies? McKibbin had her Bible, a notebook, and a pencil. Her other books, left at San Pasqual but soon retrieved, included Ellen G. White’s book Christ Our Savior, W. O. Palmer and J. E. White’s Gospel Primer, Goodloe Harper Bell’s Elementary Grammar, and John Harvey Kellogg’s First Book in Physiology and Hygiene. And, of course, they had copies of Our Little Friend.

More than 30 children showed up, more than would fit in the cast-off seats. And, surprise, nine grades, not just eight!

Each night McKibbin wrote out Bible lessons and nature study lessons. Her salary was the grand sum of $15 per month, with $5 per month paid to the family who boarded her. Sick with pneumonia, she started a six-week Christmas break near the beginning of December. Before returning from San Diego, she pleaded with the board to batten the exterior walls, plaster the inside, add two more windows, and provide more blackboards. This they did, but in doing so spent most of their money, and by March the board summoned Alma and sadly explained that they could no longer pay her and would have to close the school.

“I signed a contract,” she countered, “and I will keep it. I will teach whether you can pay me or not. But I still need a place to sleep and food to eat. Could you still take care of my room and board?”

After some whispering on the board, one woman volunteered to sell her family heirloom sideboard. The $15 she received paid the last three months of McKibbin’s room and board.

Training Teachers

At camp meeting that summer McKibbin was invited to teach the church school at Healdsburg College. Then, wonder of wonders, the conference organized a summer school to instruct teachers! McKibbin was thrilled. At last she could learn how to teach a church school.

But the night before the summer session began, M. E. Cady, who was slated to teach the class, called McKibbin into his office. “I’ve just been called to become president of Healdsburg College,” he said. “I have to go back to Nebraska to get my wife and belongings.”

But the night before the summer session began, M. E. Cady, who was slated to teach the class, called McKibbin into his office. “I’ve just been called to become president of Healdsburg College,” he said. “I have to go back to Nebraska to get my wife and belongings.”

“Well,” McKibbin responded, “who’s going to teach the summer school?”

“Elder Ballenger will be in charge, but because you’re the only one here who has ever taught a church school, you’ll give the instruction on methods.”

McKibbin spent another awful night—and each night for the rest of the summer. She prepared the next day’s instruction for the 11 new teachers enrolled in the program. And those lessons, written out each evening for the next day’s lectures, became the core curriculum for the Seventh-day Adventist elementary school system.

In the following months, along with teaching at Healdsburg, McKibbin edited those notes and printed—one signature at a time—the chapters of our first elementary school textbooks. Soon desperate church school teachers were receiving, via parcel post, these sections of books, which they used for the few weeks until the next installment arrived.

Each signature was sent out punched to receive shoestrings, and by the end of the year the “shoe-string textbooks” became the first in the Seventh-day Adventist elementary school system.

Signatures that followed were, of course, bound; and year by year McKibbin produced books for different grade levels and different subjects.

A Presence Still Felt

When I attended Pacific Union College in the early 1970s, Floyd Rittenhouse, president of the college, presented Alma McKibbin, at the age of 100, an honorary doctoral degree. In 1972 she was awarded the Seventh-day Adventist educational Medallion of Merit, and the administration building of Pacific Union College Preparatory Academy is named in her honor.

Ellen White could have been speaking about Alma Baker McKibbin when she wrote: “Nothing is apparently more helpless, yet really more invincible, than the soul that feels its nothingness and relies wholly on God” (Prophets and Kings, p. 175).

_________

Stanley D. Hickerson is pastor of the Stevensville, Michigan, Seventh-day Adventist Church. This article was published August 25, 2011.