mid the “sizzling” heat of Takoma Park young teacher Clifton L. Taylor arrived at Washington Missionary College (now Washington Adventist University) for meetings.1 Although he arrived late, he quickly caught up to speed about what was going on from other conference participants. Church president A. G. Daniells had cast a broad vision for the gathering of denominational thought leaders. This vision included bringing the most talented educators, individuals such as Taylor, from across North America to talk about issues in a clear yet discreet manner.2

mid the “sizzling” heat of Takoma Park young teacher Clifton L. Taylor arrived at Washington Missionary College (now Washington Adventist University) for meetings.1 Although he arrived late, he quickly caught up to speed about what was going on from other conference participants. Church president A. G. Daniells had cast a broad vision for the gathering of denominational thought leaders. This vision included bringing the most talented educators, individuals such as Taylor, from across North America to talk about issues in a clear yet discreet manner.2

Although the meetings had started on Tuesday evening, by the time Taylor arrived on Thursday, conferees were getting ready for their first break—time to celebrate the Fourth of July American independence holiday. One group, a group that Taylor joined, went downtown to the United States capital, where they followed megaphone announcements as Jack Dempsey won the world heavyweight boxing championship in just three rounds!3

The stifling heat and boxing match would mirror the theological turmoil that occurred over the next month at the 1919 Bible Conference.4 Although the concept of Bible conferences was certainly not new to Adventism, this conference was different from previous meetings. It was the first time that such a highly educated group of educators, editors, administrators, and other thought leaders had gathered to discuss such a plethora of controversial topics. The planning committee had done this deliberately. The meetings were closed to anyone except those invited by the General Conference Executive Committee specifically so that they would feel free to express their viewpoint without fear of recrimination.

The 1919 Bible Conference would be the first gathering of Adventist scholars, 65 altogether (including three women), where enough people present who were trained in biblical languages were able to debate the etymology of words in Hebrew, Aramaic, or Greek. Some conferees had attended seminars on the “historical method” and not only were conversant in the latest methods for doing historical research, but were well-versed in scholarly journals and even in French and German publications. Some present had graduate training in theology, history, and, of course, biblical languages. With so much invested, it is no wonder that by the Monday following his arrival Taylor would describe that the “big guns” were “firing broadsides” as they debated issues.5

The Prophetic Conferences

At the outset of the meeting Daniells noted that the 1919 Bible Conference was modeled after similar conferences, organized by conservative Christians across the United States. These meetings, held by individuals later dubbed as the historical “Fundamentalists,” were highly successful in capturing the attention of Americans regarding the second coming of Christ. Several Adventist Church leaders attended these meetings, and Daniells himself cited these other conservative Christians as doing the very work that Adventists should be doing.6

Americans were going through a period of intense cultural change. The United States was now a melting pot of religions in a culture that was no longer predominantly Protestant. The recent World War I (1914-1918) and the influenza pandemic of 1918 made people realize their mortality and shook their confidence in humanity. Fundamentalists harnessed this angst by calling the attention of people in large cities on an unprecedented scale to the fact that Jesus was coming.

F. M. Wilcox, the editor of The Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, noted that these prophecy conferences were some of the most significant events in Christian history—parallel to Luther’s ninety-five theses and other great events—and that these conservative Christians just needed to follow their convictions about the authority of Scripture and the danger of Modernism. With some help on the part of thoughtful Adventists they would become Seventh-day Adventists too. While Wilcox felt rather at home at these meetings, he was very much aware of some of the theological misconceptions espoused there.7

Daniells shared a conviction with other church leaders that if Seventh-day Adventists could unite theologically, this conference would be the first of many conferences that would draw the attention of the world to the fact that Jesus was coming again. The 1919 Bible Conference was therefore a meeting that would unite the denomination and ultimately call the attention of the world to what Adventists believed about the end-time.8

Adventist Hermeneutics

Most of the differences among the participants of the conference revolved around issues in Adventist eschatology, issues such as the identity of the “king of the north” in Daniel and problematic dates in the sequence of prophetic chronology. Most Adventists today would quickly yawn and lose interest if they were somehow transported back in time to the 1919 Bible Conference. Yet the issues held a lot of significance to those present because they represented two different ways of interpreting inspired writings and thus concerned hermeneutics. Although the issues were modest, it became clear at the very beginning of the conference that two Adventist hermeneutical schools existed in 1919.9

One of the groups, the self-styled “progressives,” emphasized the historical context of both the Bible and Ellen White’s statements. The meaning of an event was more important than the validation of a historical date. Thus persons such as W. W. Prescott were willing to revise traditional Adventist prophetic dates depending on historical accuracy (Prescott spent a great deal of time debating whether A.D. 538 was the most accurate date for the beginning of the 1260-day prophecy). Progressives believed that the Word of God was “verbally inspired” but not tied to inerrancy (that there are no mistakes when it comes to inspired writings). Thus the progressives developed a more flexible hermeneutic that utilized the latest historical research.

One of the groups, the self-styled “progressives,” emphasized the historical context of both the Bible and Ellen White’s statements. The meaning of an event was more important than the validation of a historical date. Thus persons such as W. W. Prescott were willing to revise traditional Adventist prophetic dates depending on historical accuracy (Prescott spent a great deal of time debating whether A.D. 538 was the most accurate date for the beginning of the 1260-day prophecy). Progressives believed that the Word of God was “verbally inspired” but not tied to inerrancy (that there are no mistakes when it comes to inspired writings). Thus the progressives developed a more flexible hermeneutic that utilized the latest historical research.

A second hermeneutical approach was represented by Adventist “traditionalists.” This group emphasized that the Bible and Ellen White’s writings had equal authority, and thus both were “verbally inspired.” Some traditionalists, such as B. G. Wilkinson, grew very uncomfortable with persons such as Prescott who questioned well-established dates such as A.D. 538, noting the rich heritage of prophetic interpretation dating back to Uriah Smith, William Miller, and others who had laid a solid foundation. It appears that this group took a more literalist approach to interpreting Scripture and history, and argued that anyone who questioned well-established prophetic dates risked undermining the validity of Adventist eschatology altogether.

What divided these two groups were the presuppositions through which they approached Scripture. Both groups recognized that there had to be principles to interpret Scripture, and the first week of the conference was devoted to discussions about what rules they could mutually agree upon. Despite the agreed-upon lists and the meticulous training in biblical studies of most participants, there were still disagreements.

In actuality both groups had much more in common than they realized. Both groups believed in genuine predictive prophecy, the historicity of the Bible, and in their polemic against Modernist Christians; both groups maintained that Scripture was “verbally inspired.” However, although progressives maintained the infallibility of Scripture as a whole, they would not hold that Scripture was inerrant in every chronological, numerical, historical, or linguistic detail. This made them less dogmatic about those details and more open to question established dates in Adventist eschatology. The traditionalists presupposed that Scripture was inerrant in every detail. They maintained a very literal reading of Scripture—taken at face value and not questioned—and therefore vigorously defended these established historical dates.

The planning committee allowed representatives from both camps to present their viewpoints during the 1919 Bible Conference. There was a common conviction espoused by church leaders that Adventist theology would not lose anything by a careful investigation of the reasons why Adventists held the beliefs they did. After all, Adventists were a people of the Book, the Bible, and a careful investigation would lead them only into a deeper understanding of truth. Despite this, disagreements occurred. Strong personalities such as Prescott could be formidable to contend with.

In the end it was clear that “a large number of difficult questions” were discussed. Even church president A. G. Daniells felt overwhelmed by the number of disputed points. At one point he surmised that he wished he could “send the king of the north and the two-horned beast together up in a balloon” and thus be rid of these controversial issues. They made his head “whirl” as he grew tired of interpretative disagreements.10

The Pivotal Discussion About Ellen White

In the midst of such heated disagreements over Adventist hermeneutics it is not surprising that both the progressives and the traditionalists would appeal to Ellen White’s writings to settle conflict. Although her writings were frequently referenced throughout the 1919 Bible Conference, they did come up specifically at four pivotal times during the overall meeting.

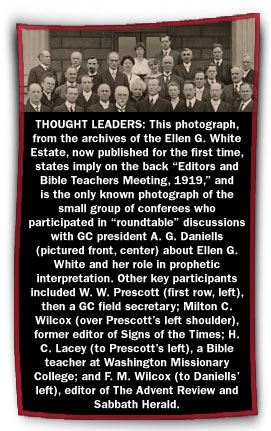

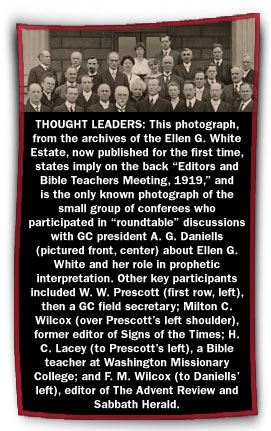

In the first discussion on July 16, 1919, Daniells realized that the issue of Ellen White’s writings needed to be addressed. The need had arisen because of historical difficulties and a major discussion about her writings that had occurred a few days earlier on July 10. From what little is extant of this discussion it seems that Daniells felt defensive because some had portrayed or perceived him as somehow undermining the gift of prophecy. He felt that those present needed to understand from his personal experience with Ellen White that this could not be true. As the Bible conference closed and as the educators continued to meet, Daniells was called back to share with those still gathered—about 28 by this time—his understanding of the nature and authority of Ellen White’s writings.

It was obvious that Adventist educators were concerned about the two contrasting hermeneutics expressed and the implications this had for the interpretation of Ellen White’s writings. Although both the progressives and the traditionalists believed her writings were inspired, progressives such as Prescott knew from personal experience that Ellen White was not infallible when it came to every historical detail. Some of the younger traditionalists—many of whom had not worked closely with Ellen White and were influenced by the rising Fundamentalist movement—maintained that her writings were infallible and therefore equal to Scripture. In recognizing these two approaches to the inspiration of Ellen White’s writings several teachers called upon Daniells and other church leaders to publish a pamphlet and clarify these issues. They were keenly aware that students in their classrooms would push them to clarify these issues. Daniells responded that the best way to resolve this was to set up a committee to look into the issue. There is no evidence that the General Conference Committee ever seriously considered the suggestion. The problem is that the issue of Adventist hermeneutics, particularly how it related to Ellen White, would not go away and would be at the basis of every debate within the denomination that persisted through the remainder of the twentieth century. In more nuanced forms the differences over hermeneutics continue to create theological tension within the denomination up to the present.

Significance of the Conference

The 1919 Bible Conference illustrates the danger of theological polarization. The real significance of the historic gathering is that it showcases an increasing polarization that had been growing within Adventism, and came out clearly in the debates that occurred. The self-styled progressives and traditionalists were both much closer to each other than either group realized, but as they debated, they pushed each other further apart.

One of my seminary teachers would sometimes tell his students that there should be an eleventh commandment in the Bible: “Thou shalt not do theology against thy neighbor.”11 Although church leaders saw the importance of ?having candid discussions as a key to attaining theological unity, unfortunately it appeared to have the opposite effect. There is no indication that the two camps continued to dialogue after the meeting. Instead, it would be 33 years (an entire generation) before church leaders would carefully try again to have another major Bible conference.

One of my seminary teachers would sometimes tell his students that there should be an eleventh commandment in the Bible: “Thou shalt not do theology against thy neighbor.”11 Although church leaders saw the importance of ?having candid discussions as a key to attaining theological unity, unfortunately it appeared to have the opposite effect. There is no indication that the two camps continued to dialogue after the meeting. Instead, it would be 33 years (an entire generation) before church leaders would carefully try again to have another major Bible conference.

The 1919 Bible Conference furthermore provides insight into a critical period in Seventh-day Adventist history—a time when the denomination was wrestling with the nature and authority of Ellen White’s writings soon after her death in 1915. Issues surrounding the nature and authority of her writings came up in reference to settling eschatological questions (church leaders had not intentionally planned before the meeting to formally discuss the nature and authority of her writings), yet the two hermeneutical camps would articulate two different ways to approach inspired writings, including Ellen White’s writings, and the relationship of her writings to the Bible. These issues were not settled in 1919, but became a topic of debate through the rest of the twentieth century. What did catch most Adventists ?by surprise, after the 1919 Bible Conference transcripts were discovered in 1974 in the newly organized General Conference Archives, was the candor and extent of such discussions. Although the transcripts were never published, there is no evidence to suggest that they were “hidden” or kept “secret” by church leaders. Some excerpts were published in Spectrum, which startled many Adventist academics in the 1970s who realized that they were not the first ones who were wrestling with the never-ending debate over Adventist hermeneutics and inspiration.12

Finally, the 1919 Bible Conference reveals the pervasive influence of the historical Fundamentalist movement within Adventism. Both the progressives and the traditionalists hailed the rising prophecy conference movement as a wonderful work that Adventists should be doing. Although Adventists wanted to have the same kind of success that Fundamentalists were having, neither group realized that in their mutual antipathy to change and facing the threat of Modernism, few recognized that the Fundamentalist stance on inspiration would be especially problematic for Adventist hermeneutics.

__________

1Clifton L. Taylor diary, photocopies in the possession of the author, the original in the possession of the grandson of C. L. Taylor.

2Report of Bible Conference, Held in Takoma Park, D.C., July 1-19, 1919 (hereafter referred to as RBC), July 1, 1919, pp. 9-16.

3Clifton L. Taylor diary.

4Pinpointing the exact dates of the 1919 Bible Conference is tricky when seeking to consolidate official agendas, votes, minutes, and final reports. It appears that the Bible conference ran from July 1 to 19, with a history and Bible teachers’ council that met at times for evening sessions during the Bible conference period and continued into August.

5For an overview of the 1919 Bible Conference, see Michael W. Campbell, “The 1919 Bible Conference and Its Significance for Seventh-day Adventist History and Theology” (Ph.D. diss., Andrews University, 2008).

6Campbell, “1919 Bible Conference,” pp. 22-59.

7F. M. Wilcox, “A Significant Religious Gathering: A Bible Conference on the Return of Our Lord,” The Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, June 13, 1918, pp. 2, 4, 5.

8RBC, July 1, 1919, pp. 9-16.

9For a more detailed analysis of these two hermeneutical camps, see Campbell, “1919 Bible Conference,” pp. 102-172.

10RBC, July 17, 1919, pp. 996-998.

11George R. Knight, GSEM534 Development of SDA Theology, 2001.

_______________

Michael W. Campbell is pastor of the Montrose and Gunnison Seventh-day Adventist Churches in Western Colorado. The 1919 Bible conference was the subject of his doctoral dissertation. This article was published January 28, 2010.

One of the groups, the self-styled “progressives,” emphasized the historical context of both the Bible and Ellen White’s statements. The meaning of an event was more important than the validation of a historical date. Thus persons such as W. W. Prescott were willing to revise traditional Adventist prophetic dates depending on historical accuracy (Prescott spent a great deal of time debating whether A.D. 538 was the most accurate date for the beginning of the 1260-day prophecy). Progressives believed that the Word of God was “verbally inspired” but not tied to inerrancy (that there are no mistakes when it comes to inspired writings). Thus the progressives developed a more flexible hermeneutic that utilized the latest historical research.

One of the groups, the self-styled “progressives,” emphasized the historical context of both the Bible and Ellen White’s statements. The meaning of an event was more important than the validation of a historical date. Thus persons such as W. W. Prescott were willing to revise traditional Adventist prophetic dates depending on historical accuracy (Prescott spent a great deal of time debating whether A.D. 538 was the most accurate date for the beginning of the 1260-day prophecy). Progressives believed that the Word of God was “verbally inspired” but not tied to inerrancy (that there are no mistakes when it comes to inspired writings). Thus the progressives developed a more flexible hermeneutic that utilized the latest historical research. One of my seminary teachers would sometimes tell his students that there should be an eleventh commandment in the Bible: “Thou shalt not do theology against thy neighbor.”11 Although church leaders saw the importance of ?having candid discussions as a key to attaining theological unity, unfortunately it appeared to have the opposite effect. There is no indication that the two camps continued to dialogue after the meeting. Instead, it would be 33 years (an entire generation) before church leaders would carefully try again to have another major Bible conference.

One of my seminary teachers would sometimes tell his students that there should be an eleventh commandment in the Bible: “Thou shalt not do theology against thy neighbor.”11 Although church leaders saw the importance of ?having candid discussions as a key to attaining theological unity, unfortunately it appeared to have the opposite effect. There is no indication that the two camps continued to dialogue after the meeting. Instead, it would be 33 years (an entire generation) before church leaders would carefully try again to have another major Bible conference.