pace is an important coordinate of our lives.

pace is an important coordinate of our lives.

Personal space (sometimes with bigger, other times with smaller bubbles), public space, digital space, virtual space, and, yes, also sacred space play important roles in our communities.

Space is often the domain of countries (and in the past many a seemingly minor border dispute turned into a major war). Human life and activities are measured in time and have coordinates that can provide a GPS location—space.

During the past 20 years as I lived and worked in different cultures, I’ve noticed that space is not perceived equally for different people and societies. I’ve also realized that space is an important element in Scripture. Accompany me on a quick fly-by view of the importance of sacred space in Scripture. Let’s explore the connection between space and architecture and see what this tells us about God and our perception of God. Closer to home, let’s also scan Adventist places of worship and think about how they communicate our theology to the world in which we live. Join me for this “space trip”—and make sure that your seat belts are securely tightened.

Sacred Space

Space is a great teaching tool. It helps to focus attention, and often the interplay between sound and space (and movement) helps to etch something into our brain that needs more permanent memorization. The Greek philosopher Aristotle is said to have taught his disciples while walking from one place to the other. Jesus did the same several centuries later (Luke 6:1-5). Many years ago when studying theology at Bogenhofen Seminary in Austria I remember extensive walks with vocabulary flash cards in hand that made Hebrew and Greek so much easier.

Space is a great teaching tool. It helps to focus attention, and often the interplay between sound and space (and movement) helps to etch something into our brain that needs more permanent memorization. The Greek philosopher Aristotle is said to have taught his disciples while walking from one place to the other. Jesus did the same several centuries later (Luke 6:1-5). Many years ago when studying theology at Bogenhofen Seminary in Austria I remember extensive walks with vocabulary flash cards in hand that made Hebrew and Greek so much easier.

Space is often used in biblical texts to communicate theology. This actually piqued my interest when I read the story of the tower builders of Babel in Genesis 11 some years ago.1 The theological motivation of the anonymous builders to make a name for themselves (Gen. 11:4) drives them up to heaven—higher and higher—while God, who sees their misguided motivation, comes down and confuses their language.

Eden Space

Most religions have marked sacred space—space where god and humankind can meet. According to the biblical Creation account, God created not only the conditions necessary for life on this planet and its inhabitants—He actually created a special location where the new inhabitants of earth would grow and interact with their Creator. Eden was a real place, full of natural beauty, where God would meet His creatures in the coolness of the evening (Gen. 3:8).

I imagine clusters of trees, panoramic views overlooking slow-flowing rivers, sloping horizons full of colors, and somewhere in the midst of it all a tree. “Don’t eat from it,” was the clear message from God, and somehow the tree of the knowledge of good and evil must have become a central focal point for the first human inhabitants of Eden.

I don’t need to retell the sad story of the Fall and the subsequent expulsion of our first parents from the ideal garden. Borders and frontiers were the result of the entrance of sin, and space became fragmented—echoing the increasing division between people and God and His creatures. Let’s fast-forward to the moment when Israel actually became a people during the wilderness wanderings, as this will help us understand further the importance of space—especially sacred space.

Tabernacle/Temple Space

Mount Sinai marked a crucial time for Israel as a people. It was the moment when they could breathe in deeply—the Egyptians were not chasing them anymore. It was also the moment when they became reacquainted with Yahweh, the God of the patriarchs. It was the moment when the covenant between God and Abraham and his descendents was officially ratified and they received, as part of a great audio-visual production (Ex. 19:16, 18, 19), the expression of God’s character, His law.

Following this highly significant moment God told Moses to build a tent, known as the tabernacle or tent of meeting (Ex. 25:8, 9), that would follow the basic pattern of a heavenly reality and had two key objectives: First, it provided a tangible place where God could meet His newly liberated people.2 Second, it functioned as a “LEGO-type” model of the plan of salvation and taught how salvation works.

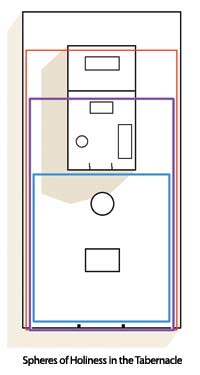

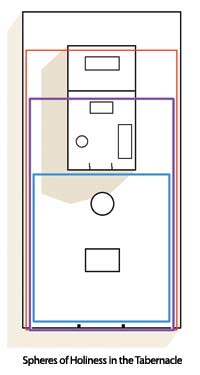

The tabernacle space was clearly divided into three geographical spaces as can easily be seen in the schematic illustration: the inner court was dominated by the altar of burnt offering and the water basin used for washing and cleaning the sacrificial animals as well as the officiating priests. This section was open to any Israelite (both male and female) and foreigner (Lev. 17:8; 22:18) who desired to enter the Lord’s presence and wanted to offer a sacrifice.

The next level of sacred space involved the first apartment of the sanctuary, where the smaller altar of incense, the showbread table, as well as the seven-branched lampstand stood. Only priests could enter the holy place as they presented the bread once a week (Ex. 40:23) and made sure that the lamps were burning continually. This was also the place where the blood taken from the altar of burnt offerings was sprinkled on the curtain dividing the holy place from the Holy of Holies. This last section of Old Testament sacred geography contained the ark of the covenant, and only once a year the high priest could enter this apartment during the Day of Atonement ritual that symbolically purged the sins (transmitted by proxy of the blood) from the sanctuary.

Have you noticed how closely space and function are linked in the tabernacle (as well as the later Temple) architecture? Geography was clearly divided into different spheres, and the mediating presence of a priest was required to approach God. This was no self-service, buffet-style restaurant, but rather a very practical illustration of the plan of salvation. Sin affected individuals and the community. Sin required the shedding of (innocent) blood. Sin soiled the tabernacle as a whole and required cleansing—a more complete solution. Sin was not just a misdemeanor or a nuisance. Sin was trouble and required a comprehensive answer. God’s definite answer to the sin problem would come in the future, and His name was Jesus.

New Testament Sacred Space

The destruction of the Temple by the Babylonians in 586 B.C. marked a major change in the thinking and practice of God’s people. The city in ruins, the Temple burning—the last view the exiles had of Jerusalem was devastating. Scholars believe that the Babylonian exile was the seedling for synagogue worship, even though very few pre-Christian synagogue buildings have been discovered.3

The destruction of the Temple by the Babylonians in 586 B.C. marked a major change in the thinking and practice of God’s people. The city in ruins, the Temple burning—the last view the exiles had of Jerusalem was devastating. Scholars believe that the Babylonian exile was the seedling for synagogue worship, even though very few pre-Christian synagogue buildings have been discovered.3

By the time of Jesus the synagogue had become an established place of studying the Torah, the Word of God, and a house of prayer. Even though a new Temple had been rebuilt in Jerusalem following the return from the exile (Ezra 6:13-18) and the daily sacrifices were offered there, people outside of Jerusalem met on Sabbath in synagogues. Jesus seems to have visited a synagogue weekly and was often asked to read the Scriptures—at times to the dismay of the established theological elite (Nazareth) who did not like His interpretation of the Word. Jesus often spoke about fulfillment, and much of this fulfillment went beyond prophetic texts to the core essentials of Temple ritual. His death and resurrection became the pivotal point of the fledgling Christian movement. He was the true “Lamb of God” who was taking away the sin of the world (John 1:29, 36). He was the innocent dying for the guilty. He was the God-man substituting for the sinner. Suddenly the LEGO-style model made sense, or, to say it more theologically, the type had met the antitype.

The Early Christian Church’s Search for Sacred Space

Similar to the tabernacle, space—once again—became relative. The focus was no longer on a building rising on a hill in Jerusalem. The focal point became the place where the children of God, from all nations, cultures, and ways of life, came together to worship and proclaim the risen Savior, now seated at the right of the Majesty of heaven (Acts 7:55, 56). These places were generally house churches or innocent public places somewhere in nature.4 Remember, the early church was not much appreciated by their Jewish brethren or their Gentile neighbors. Persecution kept them on the move, and they had to become creative in their search for safe meeting places.5

When Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire during the reign of Constantine in the fourth century A.D., all of this changed. Buildings began to emerge. Sometimes pagan temples that had become available were renovated to become Christian churches. Sometimes Christians built new churches. During the next 1,000 years Christianity produced an amazing number of architectural gems. Most of them had huge and lofty roofs, and the distance from the entrance to the sanctum was long and daunting. Often the preaching platform was so elevated that the standing or sitting worshipper was reminded of the worship experience by a stiff neck for a day or two.

What did these new buildings tell about the theology of their builder?6 For one, God was a distant God. He was powerful and majestic, was not approachable, could not be understood when one did not speak (or at least read) Latin, and often manifested Himself in repetitive liturgy. It was a God of awed beauty: consider the beautiful frescos, mosaics, and paintings that graced many of these Christian churches. During the Reformation of the sixteenth century many of the artistic trappings (including paintings and statues) disappeared from the Protestant churches, but the general layout remained the same. Long halls, high domes, little light. Preaching, however, became more important, and in many churches the pulpit was brought a little lower.

In later centuries (especially during Pietism’s emergence in the eighteenth century), the Word became even more important. Small groups split from the larger body of Protestantism and became Baptists, Methodists, Disciples of Christ, and others.

What Do Our Churches Say?

Toward the end of the nineteenth century a new denomination grew out of the Advent movement that had swept North America and many parts of Europe and South America. Even though its members did not plan to found yet another church, they began to build churches and sent an increasing number of missionaries to other places. Their first churches in North America did not look much different from the buildings of other established Protestant denominations. They emphasized the Word and highlighted austerity over artistry.

However, when Adventists began to fulfill the gospel commission of going to all the nations, they found that a church building also involved cultural dimensions. Undoubtedly the blueprint for most missionaries was ?the church buildings, familiar from their predominantly Western homelands, where people sat in pews, men wore suits, the aisle was in the middle, and an organ (or piano) played wonderful hymns.

However, when Adventists began to fulfill the gospel commission of going to all the nations, they found that a church building also involved cultural dimensions. Undoubtedly the blueprint for most missionaries was ?the church buildings, familiar from their predominantly Western homelands, where people sat in pews, men wore suits, the aisle was in the middle, and an organ (or piano) played wonderful hymns.

Studying biblical contextualization, they learned that in some cultures it was better to sit on the ground, take off one’s shoes, use local instruments, and sing different melodies to new rhythms, taking care not to violate the biblical principles of respect, worship, holiness, and adoration.

As I had to take off my shoes in the main church of Yangon, Myanmar, before I could enter the platform to teach the pastors of that conference, I was reminded of the interplay between space and theology, building designs and concepts about God.

What About Your Church?

What kind of God is your church building and your worship order communicating to the people around you? Is this a God who is distant and far away (placing the preaching pulpit rather high and making sure that there is a significant distance between the congregation and the speaker) or is it a church where God’s immanence is communicated by a broad, low platform and is accessible from many directions, thus creating the impression of closeness?

I liked the new campus church of the Adventist seminary at Bogenhofen in Austria. I liked the light and the many windows that can be opened in this church. It is refreshing to smell the outside air on a crisp Sabbath morning, even though this may not work if your church is in the center of a huge city full of traffic, congestion, and pollution. Yes, like so many others, I am culturally biased.

The Living House

Did you know that one of the metaphors that Paul used to refer to the church is a building? The Epistle to the Ephesians contains a number of these references. We (i.e., the church) are God’s house (2:20, 22), built upon the foundation of the apostles and prophets (2:20). Jesus Christ is the living door (or gate, John 10:9), the cornerstone of this living building (Eph. 2:20) that is God’s holy temple (2:21). This is truly mind-boggling: the metaphor transcends actual buildings and reminds us that sacred space involves us individually. God wants to use you and me to build up the church as a living temple, a place of refuge, a living organism that, yes, meets in buildings but goes beyond a place of worship. Can you imagine what kind of building God could have built with perfect building blocks? But He chose not to. He chose you and me, imperfect to the core, but willing to be molded to become part of “God’s house.”

This takes us beyond buildings, architecture, and set-apart sacred spaces back to the ideal, back to the Eden worship place where God freely met with our first parents. God has patiently led us the full circle back to Eden worship. Through the tabernacle (and Temple) space God has shown us the reality of a heavenly sanctuary. The tabernacle layout and function is meant to help us today, as it did the ancient Israelites, to understand the plan of salvation. God is as majestic as the grandest cathedral and yet as warm, close, and personal as a small house church. God, the master Architect, wants to move beyond buildings. He wants to use us, mold us, and transform us in this process of constructing the living temple. Even more significant: space will continue to be important in the earth to come. Jesus Himself promised to build another special place for you and me (John 14:1-3) beyond our wildest dreams where we will meet Him face to face. Now, that’s truly sacred space.

_______________

1See Gerald A. Klingbeil and Martin G. Klingbeil, “La lectura de la Biblia desde una perspectiva hermenéutica multidisciplinaria (II)—Construyendo torres y hablando lenguas en Gen. 11:1-9,” in Entender la Palabra. Hermenéutica Adventista para el nuevo siglo, ed. Merling Alomía et al. (Cochabamba, Bolivia: Universidad Adventista de Bolivia, 2000), pp. 175-198.

2An increasing number of scholars have noted the close link between Eden and the tabernacle/Temple, particularly the focal point of human-divine encounters. Compare G. K. Beale, The Temple and the Church’s Mission: A Biblical Theology of the Dwelling Place of God, New Studies in Biblical Theology, vol. 17 (Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity Press, 2004), pp. 66-80, and the many further references included there.

3Gates in ancient Israel contained side chambers that were most likely also used for the reading of the Torah. One of the earliest material evidence for synagogue buildings comes from Gamla and is dated to the first century B.C. See the standard work by Lee I. Levine, The Ancient Synagogue: The First Thousand Years, second ed. (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2005), pp. 28-42.

4See the work of Roger Gehring, House Church and Mission: The Importance of Household Structures in Early Christianity (Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson, 2004).

5A good example for a creative place of worship is the catacombs in Rome that were used by the early Christian community in Rome to worship in (relative) peace.

6Sigurd Bergmann has provided a very helpful and insightful review article about the interaction between theology and space. See Sigurd Bergmann, “Theology in Its Spatial Turn: Space, Place, and Built Environments Challenging and Changing the Images of God,” Religion Compass, vol. 1, no. 3 (2007), pp. 353-379. Online: www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/117982903/abstract. A helpful and comprehensive review of religious architecture throughout history can be found in G. J. Wightman, Sacred Spaces: Religious Architecture in the Ancient World, Ancient Near Eastern Studies Supplement, vol. 22 (Leuven-Paris: Peeters, 2007).

____________________

Gerald A. Klingbeil is an associate editor of the Adventist Review, who enjoys spacious views, warm fellowship, and the diversity of the many members of the living temple. This article was printed December 10, 2009.

Space is a great teaching tool. It helps to focus attention, and often the interplay between sound and space (and movement) helps to etch something into our brain that needs more permanent memorization. The Greek philosopher Aristotle is said to have taught his disciples while walking from one place to the other. Jesus did the same several centuries later (Luke 6:1-5). Many years ago when studying theology at Bogenhofen Seminary in Austria I remember extensive walks with vocabulary flash cards in hand that made Hebrew and Greek so much easier.

Space is a great teaching tool. It helps to focus attention, and often the interplay between sound and space (and movement) helps to etch something into our brain that needs more permanent memorization. The Greek philosopher Aristotle is said to have taught his disciples while walking from one place to the other. Jesus did the same several centuries later (Luke 6:1-5). Many years ago when studying theology at Bogenhofen Seminary in Austria I remember extensive walks with vocabulary flash cards in hand that made Hebrew and Greek so much easier. The destruction of the Temple by the Babylonians in 586 B.C. marked a major change in the thinking and practice of God’s people. The city in ruins, the Temple burning—the last view the exiles had of Jerusalem was devastating. Scholars believe that the Babylonian exile was the seedling for synagogue worship, even though very few pre-Christian synagogue buildings have been discovered.3

The destruction of the Temple by the Babylonians in 586 B.C. marked a major change in the thinking and practice of God’s people. The city in ruins, the Temple burning—the last view the exiles had of Jerusalem was devastating. Scholars believe that the Babylonian exile was the seedling for synagogue worship, even though very few pre-Christian synagogue buildings have been discovered.3 However, when Adventists began to fulfill the gospel commission of going to all the nations, they found that a church building also involved cultural dimensions. Undoubtedly the blueprint for most missionaries was ?the church buildings, familiar from their predominantly Western homelands, where people sat in pews, men wore suits, the aisle was in the middle, and an organ (or piano) played wonderful hymns.

However, when Adventists began to fulfill the gospel commission of going to all the nations, they found that a church building also involved cultural dimensions. Undoubtedly the blueprint for most missionaries was ?the church buildings, familiar from their predominantly Western homelands, where people sat in pews, men wore suits, the aisle was in the middle, and an organ (or piano) played wonderful hymns.