hat voice! Most of those engaged in the Adventist culture of the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s instantly recognize the velvet contralto of Del Delker. She, along with H.M.S. Richards, Sr., H.M.S. Richards, Jr., and the King’s Heralds quartet, crisscrossed much of North America with the Voice of Prophecy’s message: “Lift up the trumpet and loud let it ring, Jesus is coming again!”

hat voice! Most of those engaged in the Adventist culture of the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s instantly recognize the velvet contralto of Del Delker. She, along with H.M.S. Richards, Sr., H.M.S. Richards, Jr., and the King’s Heralds quartet, crisscrossed much of North America with the Voice of Prophecy’s message: “Lift up the trumpet and loud let it ring, Jesus is coming again!”

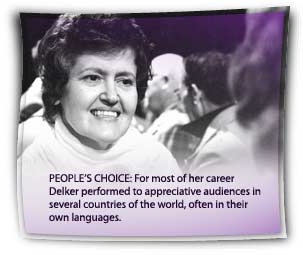

By radio broadcasts and personal appearances, Delker’s was one of the church’s most recognizable voices. And her signature song, “The Love of God,” was performed thousands of times in as many as 15 languages around the world.

Yet how Del Delker became a fixture in the Adventist music scene of the last half of the twentieth century is a tribute to God’s grace and patience, as much as it is to Delker’s musical talent.

The End of the Line

Del Delker was born in Java, South Dakota, and grew up in a single-parent home with her brother, Stanley. Her mother, Martha Hartman Delker, was one of the strong-willed Germans who carved out a living in the small towns of the Dakotas. Andrew and Martha Delker were divorced before Del was born.

Young Del demonstrated a talent for music early on. In her book, Del Delker, she tells how she went missing one day at the age of 3. As time went on her mother became more frantic and enlisted many of the neighbors to help find Del. “Then the phone rang. On the other end was the manager of the local bank. ‘Martha, are you missing something?’ the banker asked.

Young Del demonstrated a talent for music early on. In her book, Del Delker, she tells how she went missing one day at the age of 3. As time went on her mother became more frantic and enlisted many of the neighbors to help find Del. “Then the phone rang. On the other end was the manager of the local bank. ‘Martha, are you missing something?’ the banker asked.

“By this time Mother was in tears, but she managed an answer. ‘Yes!’ she said. ‘I can’t find my daughter. We’ve looked all over for her. She’s gone.’

“‘Well, she’s down here, standing in front of the bank, singing for a living, and people are putting money in her hot little fists!’”

In 1931, as the Great Depression deepened, Martha, her two children, her two sisters, and one brother-in-law set out for California with $59 in Martha’s purse.

Their money ran out in Yakima, Washington, where they got jobs in a fruit cannery until they could earn enough money to continue their trip to California. Martha, Stan, and Del Delker eventually settled in Oakland, where Martha worked as a caterer.

In Oakland Delker attended an Adventist school for grades 5 through 8. “The school I attended in eighth grade had pretty strict rules about dress and appearance,” she says. “One thing that wasn’t allowed was dark fingernail polish.”

And it was fingernail polish that led to a showdown between Delker and the school’s eighth-grade teacher. He warned her that the shade she was wearing was too colorful. “So, what did I do? I put on a darker shade, of course!”

When the teacher saw her, he took her to the chemistry lab and removed the polish himself. Looking back on the experience, Delker says, “I just didn’t like so many rules, so I persuaded Mom to let me go to public high school.”

Sidetracked by Grace

“I wanted to be a dance band singer,” says Delker. “My brother worked in a dance band for a while, but he didn’t want me to. When it came to secular singing he didn’t want me to live that life, because he knew what often went on behind the scenes.”

After graduating from high school, Delker worked at a bus station. With the help of a friend she met a young Marine named Bob Thompson. He told her about a place he’d discovered in Oakland called the Quiet Hour. He and Delker attended services there a few times with some of their friends. Even Delker was impressed by the genuine friendliness of J. L. Tucker and the others who operated the ministry, even after she found out it was an Adventist ministry; for even though her mother was a baptized Seventh-day Adventist, Delker was put off by the legalism she saw in some Adventists.

When Thompson was discharged from the service and returned home to Ohio, Delker found herself drawn to the friendships she had developed with those at the Quiet Hour. She recalls one evening when J. L. Tucker preached about heaven; he went into detail about the people who would be there, the friends and family members with whom they would be reunited, the beautiful plants and animals. He concluded by saying, “I want to be there, don’t you? I want to see Jesus. I want to live with Him for all eternity, don’t you?” Delker recalls that it seemed that he looked directly at her as he asked those questions.

The images created by those words captivated Delker for a couple of days—even as she applied her makeup in the morning before going to work and found herself asking, “Just how much do I have to give up in order to experience heaven?”

The images created by those words captivated Delker for a couple of days—even as she applied her makeup in the morning before going to work and found herself asking, “Just how much do I have to give up in order to experience heaven?”

Delker eventually found herself in Tucker’s office. “Pastor Tucker,” she said, “I really, really want to go to heaven.”

“You certainly can, Del,” he responded. “Just accept Jesus as your Savior and be baptized in His name.”

Then she came right to the point: “What I want to know is What do I have to give up?”

“I can still remember how he reacted,” she says. “He had a big swivel chair, and he leaned way back and kind of chuckled, then laughed right out loud.”

“‘I’ll tell you what, Del,’ he said. ‘I know there’s a lot of people in the church who have whole long lists of what you can and can’t do if you want to be a Christian—and what you can and can’t wear. But I prefer to keep it simple. Here’s what I’d say about how you look: If you can walk out of the house without drawing undue attention to yourself, you’ll be on the right track.’”

Delker looks back on that sermon about heaven as the time when she gave her heart to the Lord. In another few months she made her decision to be baptized and join the church.

Music Lessons

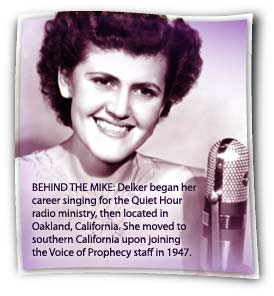

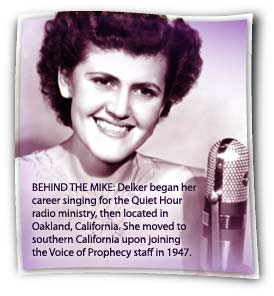

Del began using her musical talents to sing on the Quiet Hour broadcasts, which originated in Oakland, California. Within a few weeks of being baptized, she was asked to sing at a camp meeting held in Lodi, about 70 miles east of Oakland. An audience of several thousand heard her sing what would become her signature song, “The Love of God.”

The fear of singing live before a large crowd was replaced by a feeling that bordered on pride when people greeted her afterward and told her how her performance had touched their lives.

“Then it was almost like the Holy Spirit spoke right to me. It wasn’t that I heard a voice or anything, but I could just sense God speaking to me, reminding me that Jesus and my ego couldn’t sit on the throne together.”

One evening she found herself in one of the many vineyards that surrounded the campground back in 1947. As she walked down the rows of grapevines she fell to her knees and prayed,

“Lord, if my voice is going to keep me out of heaven, take it away from me.”

In response she felt a strong impression, as if God was telling her, “I’ll take care of your ego. You leave that to Me.”

Back in Oakland, Delker continued to sing without pay for the Quiet Hour broadcasts while she worked days for the Pacific Greyhound bus company and saved money to attend college in the fall.

Then one day the phone rang and someone from the Voice of Prophecy asked Del if she was interested in joining the staff of that ministry. “I was mainly interested in the Quiet Hour and was perfectly content to continue singing on Pastor Tucker’s broadcast until I could save up enough money to go to college,” she says. So she said no. But a few days later Del received another call from the Voice of Prophecy. Again Del replied that her plans didn’t include moving to Los Angeles. A third call from the Voice of Prophecy resulted in a similar response.

But a fourth call from the Voice of Prophecy led her to wonder whether God was leading her on a different path than she had planned for herself. After praying and seeking the counsel of friends, Del decided to walk through the door God had opened for her. J. L. Tucker, her spiritual mentor and counselor, put his seal of approval on her decision by loading up his own car with her few belongings and driving her and them to southern California.

A Slow Start

Delker joined the Voice of Prophecy when the musicians there were “supervised” by a committee at the General Conference. “I think all the members of the music department felt kind of insecure at the time,” she recalls. “It wasn’t until the middle of 1949—nearly two years after my arrival—that things finally settled down.

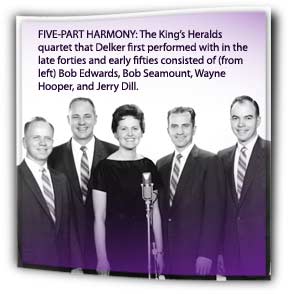

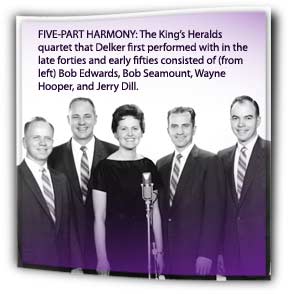

“When I showed up at the Voice of Prophecy, I was about as popular as a skunk at a picnic,” she says about her relationship with the King’s Heralds. “They didn’t know who I was; Wayne Hooper was fairly new then.”

“When I showed up at the Voice of Prophecy, I was about as popular as a skunk at a picnic,” she says about her relationship with the King’s Heralds. “They didn’t know who I was; Wayne Hooper was fairly new then.”

One of her first jobs was working with H.M.J. Richards, father of the ministry’s founder, H.M.S. Richards. Over the next several years Delker worked in several clerical positions at the Voice, while occasionally singing on the broadcasts and going out on weekend appointments with the Voice of Prophecy team. Overall, she felt underutilized and underappreciated. Several times she spoke to Elmer Walde, then associate speaker of the broadcast, about her frustration. Every time he encouraged her to stay until the uncertainties in the music department could be worked out.

“What I wanted to do after I was converted is go to college,” remembers Delker. “I wanted to go to college and meet a guy who wanted to be a minister, so I could be a minister’s wife.” Her future at the Voice seemed to be an obstacle to her own life goals.

Finally, about three years after joining the staff of the Voice, Wayne Hooper stopped by her desk and asked if they could talk. He began by saying, “I owe you an apology.” Then he went on to talk about how most of his time over the past couple of years had been consumed with organizing the music ministry of the King’s Heralds quartet, and how he viewed her presence as a complication to the goals he had for that group.

“But I was wrong,” Delker remembers him saying. “I’ve been watching you. . . . I really believe that the Lord called you here and that He has a place for you in the music ministry of the Voice of Prophecy. I want you to know that you can count on me. If there’s anything I can do to help you further your career as a singer, I’ll do it.”

Delker performed many of Hooper’s arrangements for the next 50 years. In fact, Delker’s last public performance was at Wayne Hooper’s memorial service after he lost his battle with cancer in 2007.

After five years working at the Voice full-time, Delker went to college—one year at Emmanuel Missionary College (now Andrews University), and four years at La Sierra College (now La Sierra University). While at La Sierra, she spent summers and weekends performing with the Voice of Prophecy team.

No Looking Back

For the next 35 years the list of musicians who performed with Delker reads like a Who’s Who of Adventist performers. They included the King’s Heralds (in all its iterations), the Heralds (when the Voice eliminated its music department for cost savings in 1982), Brad Braley, Gordon and Phyllis Henderson, Jim Teel, Calvin Taylor, Phil Draper, Janice Wright, and (pause for dramatic effect) the Wedgwood Trio.

Harold Richards, Jr., then associate director for the Voice, had a burden for reaching young people with the gospel. In the summer of 1967 he invited the trio—Jerry Hoyle, Bob Summerour, and Don Vollmer—to travel to camp meeting appointments with him and Delker. She remembers: “When I heard Wedgwood’s music, I was thrilled. Sure it was folk music. But it was music with a positive Christian message.”

Delker went on to do a recording with the Wedgwood that met a mixed reception. Some thought Delker had sold out and become worldly, since the trio sang to a banjo, guitar, and string bass accompaniment. “One musician I had worked with in the past even wrote to me and told me I ought to go out into the woods and study the life of Christ until I was reconverted,” she says.

Still, she defends her willingness to reach out to a younger generation in a style it appreciates—which now, she notes, seems positively tame compared to some of the musical offerings performed in some Christian settings.

In 1982, when the music department of the Voice of Prophecy was disbanded, Delker was asked to stay on. She wondered how that would be possible, since her accompanist, Jim Teel, had been released along with the King’s Heralds. Little did she know that God had set in motion a chain of events that would solve that problem in a delightfully providential way.

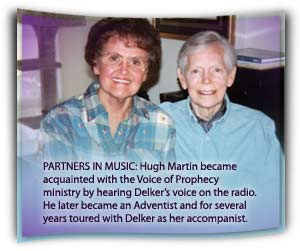

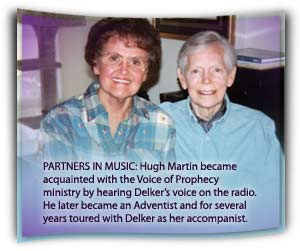

Hugh Martin is a composer and songwriter whose music and lyrics have been performed in Broadway musicals and Hollywood films. He composed the tune for “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas,” which appeared in the motion picture Meet Me in St. Louis.

In 1960, at the height of his career, he experienced an emotional breakdown. In a small hospital chapel in England he promised God that if he recovered, he would use his talents to honor Him. A few years later, back in the United States, Martin happened across a Voice of Prophecy broadcast. He later wrote to Delker: “I listened [to the Voice of Prophecy] for nine years. . . . I was not the least bit interested in sermons or messages or the Bible, I was still not there yet. But your voice captivated me, and I remember thinking, If only I could be her accompanist.”

In 1960, at the height of his career, he experienced an emotional breakdown. In a small hospital chapel in England he promised God that if he recovered, he would use his talents to honor Him. A few years later, back in the United States, Martin happened across a Voice of Prophecy broadcast. He later wrote to Delker: “I listened [to the Voice of Prophecy] for nine years. . . . I was not the least bit interested in sermons or messages or the Bible, I was still not there yet. But your voice captivated me, and I remember thinking, If only I could be her accompanist.”

In 1979 Martin was in the hospital for some tests, and he found himself sharing a room with a Seventh-day Adventist pastor, William Lester. As their conversations followed more spiritual topics, Martin and Lester began studying the Bible together and Martin was baptized.

Martin moved to Thousand Oaks, California, to be close to the Voice of Prophecy in case his services as an accompanist were needed. He met Delker on several occasions, but at the time the music program at the Voice was still intact. But in 1982 Delker approached him about being her accompanist. Over the next four summers they performed together in several places around the country. Martin went on to write new lyrics for his Christmas standard to make it say, “Have yourself a blessed little Christmas.”

Reprise

After living most of her life in southern California, Delker now lives in California’s central valley and enjoys a fairly active life. But she no longer performs in public. The years, the travel, and several surgeries over the years prevent her from traveling too far from home. Nevertheless, she has few regrets. Her many travels, the more than 40 albums she has recorded, and the many lives she’s touched for Christ make hers a life well-lived.

“The highlights of a career like mine are watching people come to Christ because He used you,” she says. “I can’t convert anyone; but the gospel does. And I’ve seen many people who have been influenced by gospel music.”

_________

Sources

Telephone interview with Del Delker, Jan. 30, 2009.

Interview with Don C. Schneider, Really Living, Aug. 24, 2006, www.biggytv.com/sda/rl/sda_rl.php.

Del Delker: Her Story as Told to Ken Wade (Pacific Press, 2002).______________

Stephen Chavez is managing editor of the Adventist Review.

![]() hat voice! Most of those engaged in the Adventist culture of the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s instantly recognize the velvet contralto of Del Delker. She, along with H.M.S. Richards, Sr., H.M.S. Richards, Jr., and the King’s Heralds quartet, crisscrossed much of North America with the Voice of Prophecy’s message: “Lift up the trumpet and loud let it ring, Jesus is coming again!”

hat voice! Most of those engaged in the Adventist culture of the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s instantly recognize the velvet contralto of Del Delker. She, along with H.M.S. Richards, Sr., H.M.S. Richards, Jr., and the King’s Heralds quartet, crisscrossed much of North America with the Voice of Prophecy’s message: “Lift up the trumpet and loud let it ring, Jesus is coming again!”  Young Del demonstrated a talent for music early on. In her book, Del Delker, she tells how she went missing one day at the age of 3. As time went on her mother became more frantic and enlisted many of the neighbors to help find Del. “Then the phone rang. On the other end was the manager of the local bank. ‘Martha, are you missing something?’ the banker asked.

Young Del demonstrated a talent for music early on. In her book, Del Delker, she tells how she went missing one day at the age of 3. As time went on her mother became more frantic and enlisted many of the neighbors to help find Del. “Then the phone rang. On the other end was the manager of the local bank. ‘Martha, are you missing something?’ the banker asked. The images created by those words captivated Delker for a couple of days—even as she applied her makeup in the morning before going to work and found herself asking, “Just how much do I have to give up in order to experience heaven?”

The images created by those words captivated Delker for a couple of days—even as she applied her makeup in the morning before going to work and found herself asking, “Just how much do I have to give up in order to experience heaven?” “When I showed up at the Voice of Prophecy, I was about as popular as a skunk at a picnic,” she says about her relationship with the King’s Heralds. “They didn’t know who I was; Wayne Hooper was fairly new then.”

“When I showed up at the Voice of Prophecy, I was about as popular as a skunk at a picnic,” she says about her relationship with the King’s Heralds. “They didn’t know who I was; Wayne Hooper was fairly new then.” In 1960, at the height of his career, he experienced an emotional breakdown. In a small hospital chapel in England he promised God that if he recovered, he would use his talents to honor Him. A few years later, back in the United States, Martin happened across a Voice of Prophecy broadcast. He later wrote to Delker: “I listened [to the Voice of Prophecy] for nine years. . . . I was not the least bit interested in sermons or messages or the Bible, I was still not there yet. But your voice captivated me, and I remember thinking, If only I could be her accompanist.”

In 1960, at the height of his career, he experienced an emotional breakdown. In a small hospital chapel in England he promised God that if he recovered, he would use his talents to honor Him. A few years later, back in the United States, Martin happened across a Voice of Prophecy broadcast. He later wrote to Delker: “I listened [to the Voice of Prophecy] for nine years. . . . I was not the least bit interested in sermons or messages or the Bible, I was still not there yet. But your voice captivated me, and I remember thinking, If only I could be her accompanist.”