as told by PAUL CONRAD

The U.S. Army officer was clear. Either Albin concedes and compromises his beliefs, or suffers the consequences—

which Albin knew would be severe.

How can I dishonor God, who has given so much for me, even the life of His Son? he thought. How can I go against His Word?

Fully decided, Albin responded, “I’m sorry, but I cannot do as you ask. I must obey God rather than man.”

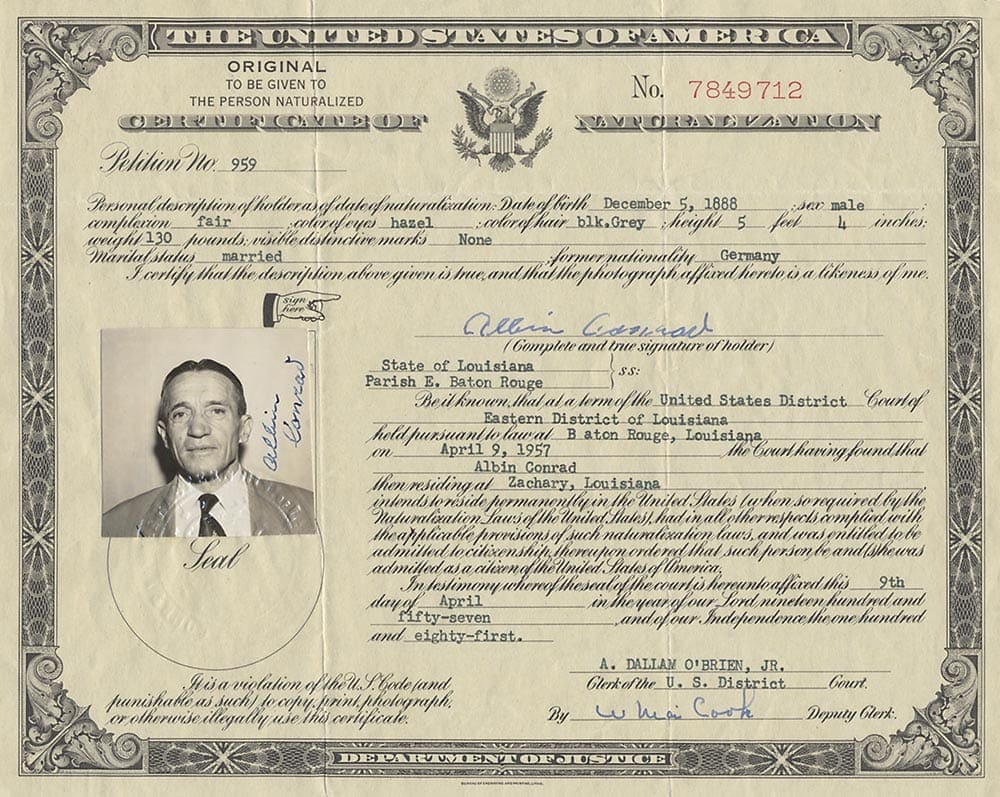

Albin Conrad, born in Obernessa, Germany, December 5, 1888, to parents Fredrick and Wilkelmia (Bubrikhauf) Conrad, immigrated to the United States in 1911 at the age of 22 on the S.S.

Kronprinz Wilhelm. His older brother, Richard, had immigrated to the U.S. some years before, and Albin was joining him. When he finally arrived in New York, however, he was met with a surprise—Richard had become a Seventh-day Adventist Christian!

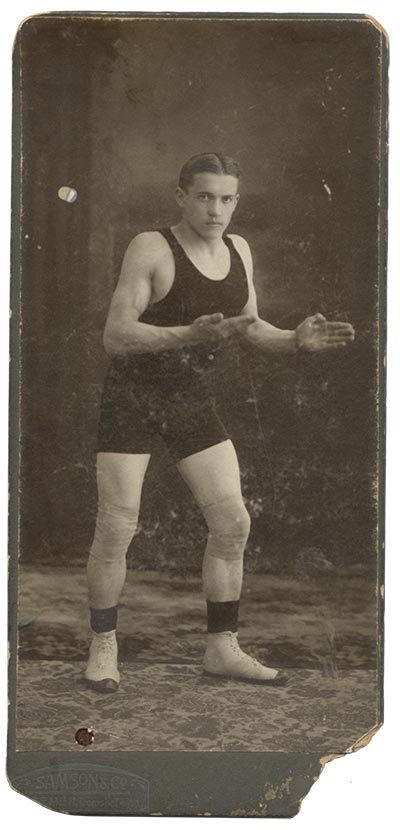

Not sure what to make of his brother’s religious “transformation,” Albin decided that it was fine for Richard, but he wanted nothing to do with it. He had little interest in God and the Bible, and instead became heavily involved in his own passion: wrestling.

“My father worked out in gymnasiums in New York City as a wrestler,” his son, Paul Conrad, says, “but his brother didn’t give up trying to share Jesus with him.”

Richard frequently discussed his beliefs with Albin and coaxed him to read various articles and tracts about God and the Bible. Finally Albin relented.

“My dad eventually agreed to read some of the papers,” Paul says, “but he felt so ashamed about reading anything religious that he hid in the bushes in New York City’s Central Park and put a blanket over his head so no one would see him reading.”

In time Albin became convinced that the Bible was true and that Saturday, the seventh-day Sabbath, is the day that the Lord asks us to keep holy—but he wasn’t yet fully committed to his newfound faith.

Albin worked as a baker, a trade he had learned as a youth in Germany. One night about midnight while taking his break, he encountered Jesus.

“My dad said he was just standing there, leaning against his workbench, when all of a sudden Jesus stood before him, with outstretched arms,” Paul says. “It was like the stories you read in the Bible. My father said he looked and looked, and then Christ just vanished. He said he was a changed man from that moment on.”

After this experience Albin enrolled in Clinton German Seminary, a Seventh-day Adventist educational institution in Clinton, Missouri. After World War I broke out in 1914, he was drafted into the U.S. Army. This was a problem for Albin, because he was a conscientious objector and refused to carry a gun. He also believed in keeping holy the biblical seventh-day Sabbath and would not work on Saturday. Military officials were not sympathetic.

“My dad first tried to get into the Medical Corps, but he was refused,” Paul explains. “The Army was bound and determined that they were going to make him carry a gun and work on Sabbath—and they took very strong measures in their attempts to do that.”

Paul says his father was beaten numerous times, sometimes until he was unconscious. He would then be revived by buckets of water being poured over him, and beaten again.

“They chained him to iron bars while standing up, 10 hours at a time. He was unable to sit down,” Paul says. “My dad said that during those times he would sing, ‘Face to face with Christ my Savior.’ This was his favorite song to his dying day.”

When Army officials realized they couldn’t break Albin’s spirit and resolve, they court-martialed him and sentenced him to 99 years of hard labor in Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, used as a military prison since the 1870s, and still in use today.

“The original part of the prison—the east side, which faces the Missouri River—is where my father was incarcerated,” Paul says. “Military prisoners serve time there today as well.”

The 1918 and 1919 annual reports of the United States Disciplinary Barracks at Fort Leavenworth tell of 92 conscientious objectors being housed there, some for political reasons, but most because of religious convictions. The reports for both years include Seventh-day Adventist among the prisoners’ affiliated denominations, and note that the main objection to bearing arms given by the prisoners is that the Ten Commandments say, “Thou shalt not kill.”

An article titled “A Sabbath School in Prison” in the Adventist Church’s

Sabbath School Worker, dated July 1919, also mentions the Fort Leavenworth Adventist inmates. It tells of a Leavenworth Sabbath school the Adventists had organized and lists the Adventists by name. Albin (his name is incorrectly spelled “Alvin” in the article) Conrad, prisoner number 14208, was among them. Article author Charles. S. Longacre, secretary of the church’s Religious Liberty Association, wrote, “It is no doubt the first Sabbath school ever organized by Seventh-day Adventists in prison,” and included a quote from Adventist prisoner Thomas J. Connors that read, “We are all cheerful in the hope of the soon coming of the Saviour, and also of a speedy deliverance from our confinement, that we may have a part in the harvest of the world, which we all feel is now ripening.”

“We have been assured by the War Department that our young men have an excellent record, and will soon be released from prison.”

The article also mentions a letter from Connors’ wife, who noted a prison riot in which the “Adventist boys, without one exception, remained faithful and loyal to the officers, and stood for law and order during the recent mutiny of more than three thousand prisoners at Leavenworth.” She added, “We have been assured by the War Department that our young men have an excellent record, and will soon be released from prison.”

Because the Adventists didn’t become involved in the mutiny, Paul says they were granted privileges, such as holding the Sabbath school class and giving Bible studies to some of the other prisoners.

After the riot, all the prisoners who were inducted into military service from west of the Mississippi River—including Albin—were transferred to Alcatraz Federal Penitentiary on Alcatraz Island in San Francisco Bay. Life there for Albin wasn’t easy. Sometimes he was placed in solitary confinement and given only bread and water to eat. At one point he was no longer given any bread. He prayed to God and was impressed to pull up some of the wooden floorboards, where he found some bread.

“Either God put the bread there, or one of the former prisoners did,” Paul says. “My father was able to survive on that bread.”

When not in solitary confinement, Albin ate in the dining hall, “one of the most dangerous places of all because the inmates had access to knives, spoons, and forks, and with these they could cause a lot of trouble,” Paul says. “The room was rigged with tear gas, so if there were problems the guards could teargas the whole room.”

He adds, “There was a window in the dining room with a beautiful view, and it must have been tough looking out from behind those bars when you knew you may be in there the rest of your life.”

Much to Albin’s surprise, when the war was over the Army gave him a dishonorable discharge. His discharge document is dated May 16, 1919. Because of the dishonorable discharge, however, he couldn’t obtain American citizenship—a dream he longed to achieve.

“During World War II, when I was a boy from ages 10 to 14, my father had to register as an alien resident,” Paul explains. “One of his alien registration books contains a list of things that my dad and his family weren’t allowed to have. We weren’t allowed to have a camera; we weren’t allowed to have a radio. They didn’t want us listening to the news or able to take pictures of anything. They considered us a threat to the U.S. government. Because we couldn’t have a radio, I remember on Sunday evenings we would go to a friend’s house to listen to the

Voice of Prophecy with H.M.S. Richards. . . .

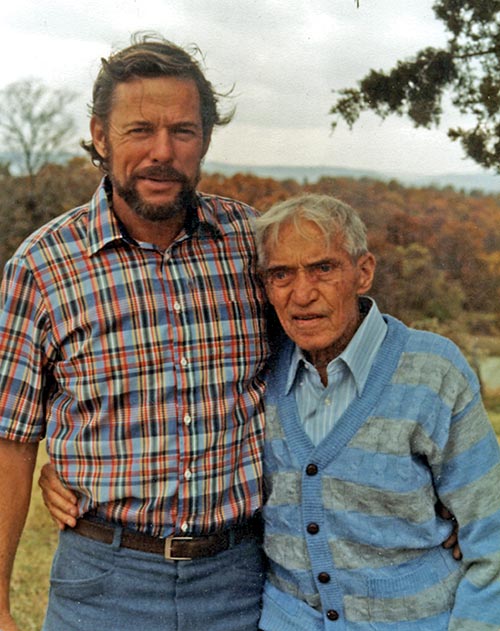

“To his dying day, at the age of 95, my father never returned to Germany, not even for a vacation,” Paul adds. “He considered the United States his home country and was loyal to it. I never once heard him say anything negative about the United States or the Army for the way they had treated him. He never ever considered going to court to fight for his rights. Instead, he counted it a privilege to be persecuted for Christ’s sake. The apostle Paul was his model.”

In 1957, after decades of rejection, and with the help of several U.S. government officials such as John E. Rankin of the U.S. House of Representatives and U.S. Army colonel E. C. Gault, as well as Adventist Church leaders, Albin’s military record was “corrected,” and he was granted American citizenship.

Church leaders via Western Union telegrams congratulated Albin on obtaining his citizenship. Longacre thanked him for his contribution to the Adventist Church heritage of liberty and human rights through his loyalty to “religious convictions while in Leavenworth prison in solitary confinement.” He added, “Your experience helped us to secure the freedom of all Leavenworth prisoners.” Harry K. Christman, circulation manager at Pacific Press Publishing Association, congratulated him on his “superb sacrificial integrity and loyalty to principle demonstrated in time of war”; and George W. Chambers, director of the General Conference Adventist Chaplaincy Ministries from 1954 to 1958, wrote, “You merit the highest commendation for the faithfulness and courage which you demonstrated when you faced the test of your religious convictions. . . . Your faithfulness under severe trial was a mighty factor in setting in motion events which led to the large measure of religious liberty enjoyed by our men in uniform today.”

A more recent letter, dated May 16, 1984, written to Albin’s son, Paul, from retired North American Division president Don C. Schneider, read, in part: “Your father’s life was a testimony to all of us who knew him. I have told the story of his time in the armed services to many young people and have used it as a challenge to them to be faithful to their God.”

Albin proved to be faithful to God not only during a time of war but also in a time of peace. His son remembers him devotedly studying his Bible every day, morning and evening.

“The Bible was his guide,” Paul says.

Albin eventually became a book salesman. He sold Bibles and other Adventist books throughout Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Florida.

“I can remember my dad being gone all week selling books,” Paul says. “He traveled in a 1929 Buick, which he fixed up with a bed. Each day as he sold books, he tried to make contact with somebody that he could go back to visit with that evening and give a Bible study to. Then after the Bible study he would ask permission to stay in his car on their property and spend the night. These types of Bible book salesmen are pretty rare in this day and age.”

While a young pastor in the mid-1960s serving in Harrison, Arkansas, Schneider remembers Albin living in a small apartment behind the church, and “every time the church was open, he would hobble across a section of lawn, come through the back door of the church, and attend every meeting we held,” Schneider said. “He would often have the prayer, and when he prayed, you knew that God was with us in that room,” he told

Adventist Review. “He would frequently walk up to me and say, ‘Brother Schneider, I pray for you every day.’ He was a really special Christian.”

Albin met his future wife, Marie Christensen, after his release from prison, and the couple married in 1926. Paul says that both his parents “sacrificed all their lives for God’s work.” When they died, they left behind little in the way of material possessions. Instead, Paul says, “they stored everything they managed to acquire in heaven. God honored them for this. They enjoyed good health and actually had need of nothing.”

Albin died on April 13, 1984, at the age of 95. His wife preceded him in death by two years. The couple is now buried in a small country cemetery in Harrison, Arkansas.

“If we’re going to reach our goal—heaven—we have to be faithful, just like my father was,” Paul says. “We must study the Bible for ourselves, be sure of what we believe, and then stand firm for God and His Word.

“May God help us to sort out the important things from the unimportant, and at last reach heaven and see our Savior face to face.”

Sandra Blackmer is an assistant editor of Adventist Review. Paul Conrad, who lives in Nucla, Colorado, is the son of Albin Conrad. Albin also had a younger son, David, who lives in Virginia.