Seventh-day Adventists have long looked to our pioneers for inspiration. As we prepare for the 60th General Conference session in San Antonio, there are lessons to learn and points of inspiration to take from the first, founding session 152 years ago, when Seventh-day Adventist leaders met in Battle Creek, Michigan, in May 1863.

That expression, “Seventh-day Adventist leaders met,” sounds so simple. But just 32 months earlier it could not have been said. For it was only as recently as October 1, 1860, at an earlier meeting in Battle Creek, that believers had agreed “that we call ourselves Seventh-day Adventists.”

1 Before then, the term Seventh-day Adventist had been used as often by enemies, as a term of abuse, as by the few members of the yet-unorganized movement that had emerged after the Great Disappointment of 1844.

At that 1860 meeting it took four days of debate to reach a consensus that if God’s remnant people formally organized their local churches and adopted a common name for themselves, they would not be retreating into Babylon. But those few steps were as far as Adventists would go. The prospect of any organization above the local congregation was unacceptable.

Yet, remarkably, within two and a half years Seventh-day Adventists in Michigan, Iowa, Vermont, Wisconsin, Illinois, Minnesota, and New York had organized seven separate associations of churches into what they called conferences (two in Iowa, one covering Illinois and Wisconsin, and the others each covering one state; the two in Iowa later merged into one). But what was recognized by many Seventh-day Adventists was that, in effect, this meant there were six Seventh-day Adventist denominations—not one. So in March 1863 James White, the unofficial (but undisputed) leader of Seventh-day Adventists, published, in the

Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, the journal that bound the widely scattered believers together (usually known then simply as the Review and Herald and today as the Adventist Review), a call for a “General Conference.”

The term

general conference had been used by the Millerites in the early 1840s; indeed, Joseph Bates had been chair of one such conference. In the 1850s the seventh-day Sabbathkeeping Adventists used the term for meetings that were open to all adherents of the Sabbatarians’ distinctive doctrines—that is, a conference, or meeting, that was general rather than local. However, by 1860 several Protestant denominations in the United States were using the term conference for a permanent association of congregations, and it was this use that the state conferences had borrowed.

Still, James White’s announcement in the March 10, 1863, issue of the

Review probably seemed to some Sabbatarians to be calling just another general meeting, though it did hint that important matters of common interest might be discussed. He wrote:

“We recommend that the General Conference be held in connection with the Michigan State Conference at Battle Creek, as early as such a gathering can be convened. . . . We suppose that it would be the pleasure of the brethren in other States, and the Canadas, to send to the General Conference either delegates or letters setting forth their opinion of the best course of action, and their requests of the Conference.”

2

So it was, on Wednesday, May 20, 1863, that 20 leaders of the embryonic Seventh-day Adventist movement gathered in Battle Creek.

There were 18 delegates from five of the six existing state conferences: Michigan, New York, Illinois and Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Iowa. The Vermont Conference (which included churches from across the Canadian border in Quebec) dispatched no delegates to Battle Creek, but two delegates were sent from the Seventh-day Adventist churches in Ohio, which had yet to organize into a conference. Also present were a number of members of the Battle Creek church, who were not official delegates of the Michigan Conference but interested observers of the proceedings. All the official delegates were men, though at least one woman, Ellen White, was among the locals who attended as onlookers. Two official delegates were laypersons, holding no ministerial credentials—and constituted two-thirds of the General Conference’s very first Nominating Committee!

The 20 delegates’ first action was to elect a temporary chair and secretary. The chair was Jotham M. Aldrich; the secretary, Uriah Smith. Aldrich was 35 and had only become a Sabbatarian Adventist in 1860; Smith was just 31 and, remarkably, was not a delegate, but one of the observers from Battle Creek. These two facts tell us something about the founders of our church. Many of them were young, and they were pragmatic. Where they saw talent, they would use it to spread the third angel’s message.

Having elected a chair and secretary, delegates and onlookers then joined in singing hymn number 233, “Long Upon the Mountains,” by Annie R. Smith, from the hymnbook James White had published in 1861. Then John N. Loughborough, of Michigan; Charles O. Taylor, of New York; and Isaac Sanborn, of Wisconsin, were chosen as a committee to inspect and verify the credentials of the delegates. This tells us something else about the men who founded the General Conference: they liked to sing hymns, and they valued proper procedure and committees. Some characteristics of our church go back to our very origins!

The next day, Thursday, May 21, 1863, was the big day. The first step was the selection of eight men to draft a constitution: Sanborn, of Wisconsin; Loughborough and Joseph H. Waggoner, of Michigan; John N. Andrews and Nathan Fuller, of New York; B. F. Snook, of Iowa; Washington Morse, of Minnesota; and H. F. Baker, of Ohio. They reported back so promptly that some preliminary work must have been done before the session and the constitution was then approved unanimously. The General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists was thus formally founded. More than a periodic meeting, it was a permanent association that would have annual sessions, with a constitution, three officers (president, secretary, and treasurer), and an executive committee.

Elections were then held. John Byington was eventually elected president (and took the chair from Aldrich); Eli Walker (another Battle Creek local who was

not a Michigan Conference delegate) was voted in as treasurer; and Uriah Smith was chosen as secretary. George Amadon, a Michigander, and John Andrews were elected to make up the executive committee with Byington. A committee was then formed (J. N. Loughborough, I. Sanborn, W. H. Brinkerhoff, J. M. Aldrich, and W. Morse) to draft a model constitution for all state conferences and the session then adjourned until Saturday night, May 23. Meeting after sunset, delegates approved the model constitution (which all conferences that wished to join the General Conference would have to adopt), and set up another committee (White, Andrews, and Smith) to report back to the 1864 session on rules for local churches to follow when organizing.

The fact that so much was achieved in such short time is striking, for our pioneers were capable of blunt, plainspoken debate when they disagreed. But our forefathers’ tendency to express themselves frankly shouldn’t be misunderstood.

On the first day of the 1860 conference James White began his first speech by addressing the chair, which was proper parliamentary procedure; but he did so in a unique way. For the chair was Joseph Bates, whom White had known for 20 years. These were his opening words: “Brother Chairman (you will permit me to call you brother chairman as Mr. is so exceedingly cold).”

3 White’s use of “Brother Chairman” instead of the orthodox “Mr. Chairman” reflects that our founders had invested everything in the Great Second Advent movement. They were bound together by deep affection.

Reporting in the next issue of the

Review, Uriah Smith wrote with satisfaction: “Perhaps no previous meeting that we have ever enjoyed was characterized by such unity of feeling and harmony of sentiment. In all the important steps taken at this Conference . . . there was not a dissenting voice, and we . . . doubt if there was even a dissenting thought.”4

This was one reason so much was accomplished in just over a day. Surely, too, as suggested earlier, some of the eight members of the constitution committee had done some drafting in advance. That was entirely proper, for all those who met at Battle Creek in 1863 knew that they needed to be more united and more organized, if, in words they voted on May 23, 1863, “the great work of disseminating light upon the commandments of God, the faith of Jesus, and the truths connected with the third angel’s message” was to be accomplished. As the preamble to the General Conference constitution stated, it was founded: “For the purpose of securing unity and efficiency in labor, and promoting the general interests of the cause of present truth.”

5

From this we learn something else about our founders: Whatever the debates of the 1850s, by 1863 they were clear: they needed to be united if they were to fulfill their divinely assigned mission. This mission was truly uppermost in their minds, rather than personal factors. We can be confident of this because, Uriah Smith’s comments notwithstanding, there

was one 1863 moment of disagreement.

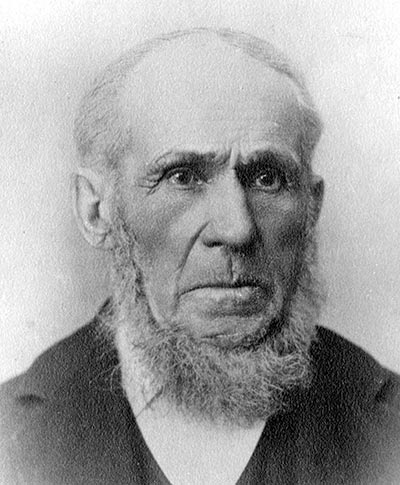

James White was unanimously chosen president, but he declined to serve. After a considerable time spent in discussion, the believers urging reasons why he should accept the position, and he why he should not, his resignation was finally accepted, and John Byington elected as president in his stead.

6

No reason was given why James White refused, but we can guess, I think. He had championed organization for several years and surely wanted it to be clear that he had done so because it was what the movement needed, not so that he could become president. White’s personal qualities were never better displayed than in this moment, arguing at length with his brethren so that they would

not make him their leader. He put the unity and mission of the new denomination above all personal factors.

Between the session’s adjournment on Thursday evening and its resumption on Saturday night, Adventist leaders turned to their favorite activity: evangelism. On Friday, May 22, the Michigan Conference’s evangelistic tent (what later generations of Adventists would call a “big tent”) “was erected on the green” near the Review and Herald office, as Uriah Smith reported. Eight evangelistic meetings were held, with delegates participating, broken by a church service on Sabbath, May 23, also held in the Second Meeting House. The session’s proceedings finally concluded with a baptism of eight new believers on the morning of Sunday, May 24.

7

Here is a last point about our founders. They valued committees, parliamentary procedure, and organization, but only as means to an end. The end they had in sight was the second coming of Christ, and a reaping of the harvest.

The spirit of ’63 is still relevant for Seventh-day Adventists. We need the same commitment to unity and to mission; we need to continue to follow proper, well-established procedures; and we need the same willingness to utilize all church members, finding ways to affirm all their talents and commitment.

We need, too, the same willingness to speak plainly to each other; but we also need the same love for each other, as brothers and sisters in Christ; and the same willingness to put the prophetic mission of this church above any considerations of self.