One of the best examples of revival in Seventh-day Adventist history is perhaps the least known. The late 1860s and early 1870s was both a formative yet tumultuous time for the denomination, officially organized in 1863. The fledgling church, forged in the heat of early-nineteenth-century revivalism, was racked by centrifugal forces that threatened to tear it apart.

Early Seventh-day Adventists had deep revivalist roots. William Miller, for example, was famous for his ability as a revivalist to lead others to Jesus. The rich evangelical heritage prioritized the Bible, the cross, and, most important, conversion. Preaching about the soon return of Jesus Christ only heightened a sense of urgency for people to change their lives.

After the Great Disappointment some Adventists, like many of their evangelical contemporaries, became skeptical—even critical—of previous revivals.1 The famous “businessman’s revival” of 1857-1858 was just one of many examples of emotionalism that early pioneers predicted would fail.2 Adventists believed that these revivals were based upon appeals to emotionalism and therefore lacked substance. In contrast, early Adventists developed a unique theology of revival that they believed led to reformation and lasting change.

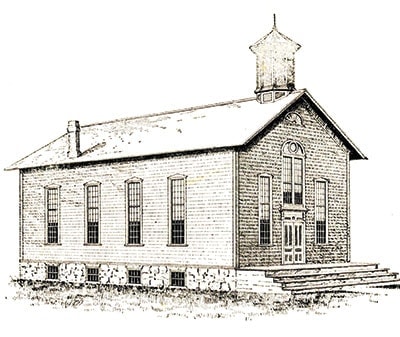

“The Battle Creek church,” admonished James White in 1872, “though large, is an unfortunate church.” Church members were poor, too busy, and, worst of all, suffered from a general spiritual apathy. Even the idea of starting a school at this particular juncture seemed like a bad idea to James and Ellen White. James wrote: “With its present feeble strength, it is simply preposterous to think of establishing a permanent school, which might call hundreds of our dear young people to the place to be exposed to unsanctified influences.”3 THIRD MEETINGHOUSE: This church was erected in 1866 in Battle Creek, Michigan, and was probably the location of the meeting attended by Ellen and James White in 1873." class="img-right" style="float: right;">

THIRD MEETINGHOUSE: This church was erected in 1866 in Battle Creek, Michigan, and was probably the location of the meeting attended by Ellen and James White in 1873." class="img-right" style="float: right;">

Ellen White issued a strongly worded protest in Testimony 23, published in September 1873, warning church leaders about their spiritual peril.4 If changes were not made immediately, the toxic spiritual environment threatened to jeopardize the entire church. Ellen White urged for immediate and sweeping changes. In short, the church desperately needed revival and reformation. Ellen White also shared concerns about false revivals. These “sensational” revivals so common of this period were “deceptions . . . calculated to lead away from the truth” through “fluctuating religious excitement.” True revival, she believed, was more modest and leads to a more “determined, persevering energy and a fixed purpose.”5

On a personal level, the events leading up to 1873 were particularly challenging for James and Ellen White. Both suffered health setbacks. Ellen suffered from a painful infection she believed was breast cancer.6 A visit to James C. Jackson’s water cure in western New York helped them realize that they urgently needed to change their lifestyle. They hoped that moving out of Battle Creek to a farm about 70 miles (113 kilometers) to the township of Greenville might help. Dr. Jackson prescribed rest, but Ellen was shown that her husband instead needed exercise.

The combination of rest and exercise outside of Battle Creek improved their health. Occasional trips to church headquarters caused stress as bills were left unpaid, along with subscription lists that were not updated. At one point the Whites found that the person left in charge of operations for the publishing house left on vacation without leaving anyone else in charge. It was no wonder that James White, after one of these visits, became extremely “discouraged and desponding.”7

On a deeper level Ellen White attributed the spiritual darkness to a rejection of the “testimonies,” or the prophetic counsels the Lord had given the church. The message of reproof was “slighted” and “repaid with hatred instead of sympathy.” By late 1873 it was apparent that both the prophet and her husband were each depressed.8

James White implemented a plan for a group of “select men” or “picked men”—spiritual leaders with business skills not under this spiritual blight—whom he called to relocate at Battle Creek. He reckoned that if 20 such families moved to church headquarters, this would bring new spiritual vitality and lessen the leadership burden.9 Although these families helped for a time, in the end it appears to have only made matters worse.

A power struggle developed in late 1872 and early 1873 over how to conduct the Review and Herald. Some of the “picked men” viewed the editor, Uriah Smith, as an obstacle to reform. Ultimately Smith quit, which prompted General Conference president G. I. Butler to mention to Ellen White: “I am sure there are whisperings all through the State [of Michigan] over Uriah’s case.”10 Rumors and gossip only accentuated this leadership crisis.

During the summer of 1872 the Whites left for the mountains of Colorado to “winter” in California. This was a time of much-needed physical and spiritual renewal. A significant breakthrough occurred for James White in December 1872 when he spent a week in personal prayer, Bible study, and reflection. He described his spiritual struggle as one characterized by “deep mourning” and “repentance” because he had not heeded the warnings directed toward him through the “testimonies” or visions from his wife.

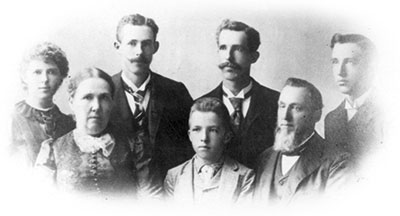

Now he recognized his own spiritual peril and circulated a tract about his new spiritual resolve. In the wake of this spiritual awakening James sought to reconcile with those whom he had wronged.11 This particular event was a turning point, after which his theology became decidedly more Christ-centered. ALL IN THE FAMILY: Uriah Smith poses with his family in the 1880s. Left to right: daughter, Annie; wife, Harriet; sons Leon, Charles, Uriah; Uriah Smith; and son Samuel." class="img-left" style="float: left;">

ALL IN THE FAMILY: Uriah Smith poses with his family in the 1880s. Left to right: daughter, Annie; wife, Harriet; sons Leon, Charles, Uriah; Uriah Smith; and son Samuel." class="img-left" style="float: left;">

At first the Whites had indicated to church leaders that they would not return to Battle Creek for the upcoming General Conference session. They now felt it was their duty to be present. They arrived on March 4, 1873, but the strain was too much. James fell back into old habits of overwork and suffered another “shock of paralysis.”

After treatments at the Health Reform Institute, the Whites resumed their original plan of spending the summer in the mountains of Colorado. While they were there the initial revival that flickered in James and Ellen White’s hearts burned into resolve and reformation. “In the Rocky Mountains,” James later reflected of their experience in the third person, “they gave themselves, their children, and their property to the Lord in a solemn covenant, praying that the Lord would . . . use them . . . in His cause.”12

The Whites considered this a personal turning point in their lives.13 They now planned to return to California for the winter. On their way they felt “solemnly impressed” to return once again to Battle Creek. After “quietly praying,” they “felt a power turning our mind around, against our determined purpose, toward the General Conference [session] to be [held] in a few days at Battle Creek.”14 They arrived on November 10, 1873,15 and remained until December 18, 1873.16

As the Whites returned to Battle Creek there was a significant church struggle over lifestyle standards. Regardless of the issues, feelings were hurt, and a general sense of suspicion pervaded the congregation. Ellen White likewise admonished church leaders such as J. N. Andrews and Uriah Smith for their lack of good judgment and failure to curb this criticism.17

The revival began in earnest as James and Ellen held daily meetings at the Battle Creek church. They held simple Bible studies in which they recounted what God had done for them in their own spiritual experience.

While the talks by the Whites are no longer extant, it seems likely that James, who had been striving to make things right with other church leaders, shared his own recent spiritual struggle. Based upon later testimonies, they also re-counted about what God had done for them as they rededicated their lives to the Lord’s work earlier that summer while in Colorado. “We bore testimony before the crowded congregation,” James noted, “that our solemn convictions were that the time to favor Zion, so far as these words could apply to our time and our wants were concerned, had come.”18 The solemn biblical messages and testimony about God’s providential leading were combined into an urgent appeal to encourage others to seek God’s blessing too.

The revival meetings were reinforced by Ellen’s personal testimonies that emphasized the need for personal conversion.19 She believed that revival and reformation occurred when individual hearts soften through the subduing influence of the Holy Spirit. As the meetings continued, confessions were made. The hearts of these early believers were “melted” as they pledged mutual love and support for one another. J. N. Andrews observed that about 200 people, many of them young people, participated in this “significant revival.” The spirit was one of sacrifice and consecration, along with a desire to save souls.20

Perhaps the most poignant aspect of the revival occurred when reconciliation took place between Uriah and Harriet Smith and James and Ellen White. In particular, Harriet publicly confessed to her role in contributing to the crisis in the Battle Creek church over lifestyle standards.21

“The strongest union now exists,” observed James White, “between those who have not been able to see eye to eye. With this improved state of things has come a spirit of prayer, and of faith, and a large degree of the Spirit of God. Not a few who have been found in uncertainty, and held by the chains of unbelief in darkness, have been set free, and have been able to triumph in the pardoning love of Christ.”22 The message of revival had indeed culminated in genuine reformation as a newfound love for Jesus anchored the hearts of Adventist believers in Battle Creek.

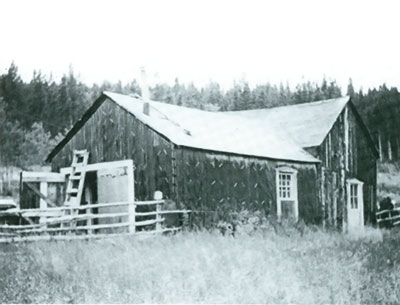

During the meetings Uriah Smith drafted a “solemn covenant,” in which members of the Battle Creek church pledged themselves to “hold up the hands of those whom God has called [the Whites] to lead out in the work, . . . and that they would faithfully regard reproof, and be true helpers in the work of God.” Although the Whites soon afterward left for California, the Battle Creek church for the first time requested James to be their pastor. After some “impressive remarks” by Uriah Smith, he proposed “that the pen, the inkstand, and the paper to which they had attached their names should be laid up together as a memorial before God.”23 James, when he later preached at the Battle Creek church, remembered the solemn memorial that was housed in a box in front of the pulpit.24 ROCKY MOUNTAIN HIGH: “White’s Ranch,” a cabin much enjoyed by James and Ellen White, near Rollinsville, Colorado." class="img-right" style="float: right;">

ROCKY MOUNTAIN HIGH: “White’s Ranch,” a cabin much enjoyed by James and Ellen White, near Rollinsville, Colorado." class="img-right" style="float: right;">

The 1873 revival helps to illustrate that early Seventh-day Adventists developed a distinctive understanding of revival and reformation. A. C. Bourdeau, in an article titled “The Revivals of the Day,” juxtaposed a Seventh-day Adventist view of revivals with popular revivals from the same period. “These revivals cannot effect any permanent good while they are based upon feeling and excitement, instead of being founded upon principle.”

Bourdeau noted overhearing a conversation on a train in which various opinions were given about recent revivals. Many who started on the path of revival afterward “quit religion” because “religion [was] driven into them merely through excitement, enthusiasm, or fanaticism, and who moved only from feeling and not from principle.”25 Bourdeau’s perspective was reinforced by numerous other early Adventists during the 1870s who struck fiercely antirevivalist cords.26

One of the most important lessons that James White discovered was that revival and reformation can never be dictated or coerced from church members. The simple act of replacing or adding new church members only made matters worse. Instead, the nucleus of revival strengthened with gradual conviction as James White recognized his own personal spiritual need and hunger. As he wrestled with God, first in California and later in Colorado, he was then in turn able to lead others through personal confession and sharing about God’s leading led in his own life.

It is significant that early Adventists who warned against popular revivals were not thereby rejecting their evangelical heritage. Instead, they were critiquing the same revivalist heritage they were very much part of, characterized by individual confession, repentance, and a general wrestling with God that led to deeper consecration. Yet they realized that any revival that would last must be anchored in conviction gained from Scripture, not emotional manipulation. True revival begins by dropping to our knees to wrestle with God.

While no revival can be fairly evaluated by statistics alone, as a historian I cannot help noticing some dramatic historical shifts. In the period leading up to 1873, church membership decreased by 15 percent; but in the three years after the 1873 revival, church growth swelled to between 15 to 25 percent, the highest denominational growth ever!27

Of course, I think the most tangible indicator that something significant had occurred was comments about a particularly meaningful celebration of the Lord’s Supper as the Whites prepared to leave. As believers washed each other’s feet and consecrated themselves anew, they remembered their individual need to partake of the sacred emblems of the body and blood of Jesus Christ.28 Clearly things had changed. Now the Whites supported starting a school in Battle Creek.29 Similar roadblocks about sending a missionary to Europe were also removed. Adventist education and mission were thus birthed out of a distinctive Adventist understanding of revival and reformation.