We and Jesus weep for different reasons. Doubly true: for Jesus shares varied griefs with us; yet His motivation for tears can be totally alien to us.

The human pattern of tears—joyful weeping and sorrowful sobbing—threatens any schedule of sense. Weddings and the wind, spankings and surprises, make us tear up. Contradictorily enough, uninhibited childhood weeping grows up to be disdain for people who do it, or, at any rate, are seen to do it. Even if the person is six-foot-four-inch Edmund Sixtus Muskie, senator from Maine, at one point front-runner for the Democrats’ nomination as presidential candidate, with an intellectual presence compared to that of Abraham Lincoln. Woe the day he was seen to weep while decrying a publication that insulted his wife! Muskie described it as a “watershed incident.” Some think it cost him the chance to run for president in 1972.1 So strong are mores against public weeping that what reporters called tears Muskie’s campaign aides claimed was melted snow [it was New Hampshire in February].2 Muskie’s indignation seems justified. The letter he denounced proved to be a hoax planted by opponents. Matters not. Reporters had publicized him as a weeper, and a weeper cannot lead America. Or Russia. Or Antarctica.

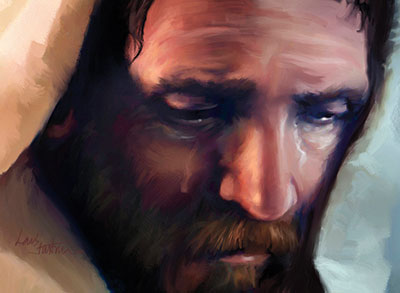

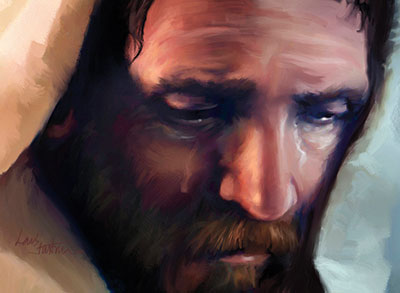

Jesus, Lord of the universe, and weeper extraordinaire, is an alien to our kingdoms. His sobs defy our formalized farces of dignity and decency, our sanitized spirituality and model maturity. When He lived here, He used to pray “with loud crying and tears” (Heb. 5:7, NASB).3 Praying with Him can teach us much about our deeply feeling God.

A mother 25 years young at the time she lost her twin babies, stillborn, thought that it might be her fault that God had chosen not to let her have her babies. After many years of our praying together, she knows His sympathizing heart much better. A colleague of mine here at the General Conference offices lost her stepbrother one Sunday in September. That Wednesday her nephew died; five weeks later her mother passed away. She says, “I still believe that God weeps every time His children mourn.” And she is right. The Bible’s God “weeps with those that weep, and rejoices with those that rejoice.”4

But we and He still do weep for different reasons. In the face of Jewish pride on Palm Sunday, contemplating Jerusalem’s vision of stunning beauty, we “see His eyes fill with tears, and His body rock to and fro like a tree before the tempest, while a wail of anguish bursts from His quivering lips, as if from the depths of a broken heart.”5 He sees our blindness, and it is His grief—blindness to our pride and its inevitable doom, remembered, more than all else, through the Bible’s briefest verse, John 11:35, “Jesus wept.” At Lazarus’ tomb He was about to give incontrovertible demonstration of His deity, silencing the Pharisees’ proof that John the Baptist’s beheading was “an unanswerable argument against Christ’s claim to be the Son of God.”6 And yet, “Jesus wept.” And “in His tears there was a sorrow as high above human sorrow as the heavens are higher than the earth.”7 For at Lazarus’ tomb God would be seen to be love and life, and Satan as His lying accuser. In a microcosm of the first rebellion, intelligent creation would see God as God, and vow that being thus, He must be destroyed. No wonder Jesus wept. We and Jesus weep for different reasons.