April 30, 1975. With the army of North Vietnam hours away from a complete takeover of Saigon, helicopters landed on the roof and in the parking lot of the American embassy to evacuate all remaining American personnel and Vietnamese nationals associated with the U.S. The helicopters would ferry passengers out the United States Navy Seventh Fleet waiting in the South China Sea. The dramatic images of that evacuation still illicit powerful memories to this day.

But what many Seventh-day Adventists today may have not been aware of was that these were dire days for the church as well during those last moments of the war in Vietnam.

Close to Tan Son Nhut airport was a hospital—Saigon Adventist Hospital, formerly known as the 3rd Field Hospital. Given to the Adventist church to run by the U.S. Army, it continued on with help from Loma Linda University. Many government officials were well acquainted with it, especially after the crash of a C-5 Galaxy Transport on April 4, 1975, loaded with orphans and their caretakers as part of Operation Babylift. Saigon Adventist Hospital provided care to all victims of that tragic accident. As the war wound down, anyone connected with the hospital and the church, which meant association with the United States, was in imminent danger once the communists rolled into Saigon.

Former ADRA president Ralph S. Watts, was the Southeast Asia union president for the church’s Far Eastern Division based in Singapore. In the week leading up to April 30, he was tasked with going to Saigon to close the hospital and facilitate the evacuation of missionaries, medical personnel, and Vietnamese church leaders. It was a nearly impossible job.

Watts documented the dramatic story of God’s leading in this event in his book, Escape From Saigon. The following is an excerpt. –Editors

The Vietnamese government had imposed a curfew on Saigon. This meant that from 8:00 p.m. until 7:00 a.m. nobody, but nobody, was allowed out on the street without proper authorization. And so, after 8:00 p.m., the streets were deserted. You would see military vehicles going by, or perhaps some ambulances, but that was it. This was the best time for us to get a lot of work done.

We drove around in a hospital ambulance, because security never stopped them. The American embassy was open at night. Several key people were at work; we would jump into a hospital ambulance and go down to the embassy. We went out to the airport. We contacted the defense attaché’s office. We carried on a lot business between 8:00 p.m. and 1:00 a.m.

Wednesday evening at the embassy I tried to find the chief political officer. He was the intelligence agent who could give us the best information. I finally located him. Just as I was beginning to talk to him, he was whisked away for a high-level meeting upstairs with the “big boys,” so his assistant came out, and we chatted for a few minutes.

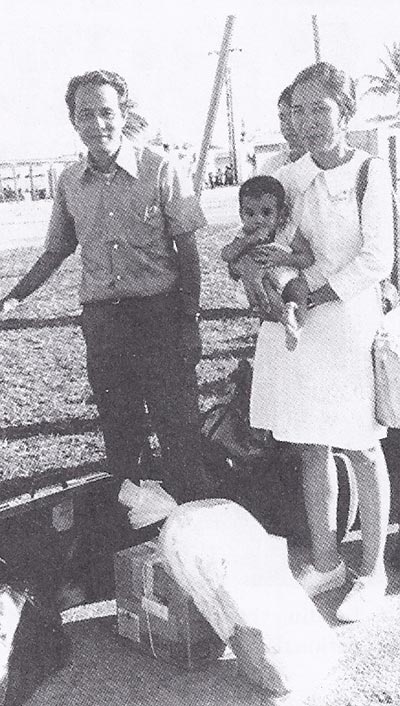

Pastor Giao: Pastor Le Cong Giao and his wife prior to leaving Vietnam. Pastor Giao was president of the Vietnam mission at the time and in imminent danger if he remained behind. Credit: Ralph S. Watts" style="font-size: 16px; float: right;" class="img-right"> I said to him, “I have got to know now exactly what the situation is. We’re done playing games.” I’m going to confess that I was a little angry. I was upset because thousands were not leaving every day. Americans were leaving. There was no problem in getting Americans out, and I knew that. Dependents of Americans, third-country nationals, and many Vietnamese were leaving the country, yet nothing was being done for our employees. The government had promised us weeks before that in the event of an evacuation, our people would be given high priority. Yet nothing was happening.

Pastor Giao: Pastor Le Cong Giao and his wife prior to leaving Vietnam. Pastor Giao was president of the Vietnam mission at the time and in imminent danger if he remained behind. Credit: Ralph S. Watts" style="font-size: 16px; float: right;" class="img-right"> I said to him, “I have got to know now exactly what the situation is. We’re done playing games.” I’m going to confess that I was a little angry. I was upset because thousands were not leaving every day. Americans were leaving. There was no problem in getting Americans out, and I knew that. Dependents of Americans, third-country nationals, and many Vietnamese were leaving the country, yet nothing was being done for our employees. The government had promised us weeks before that in the event of an evacuation, our people would be given high priority. Yet nothing was happening.

I said, “I want you to give me the straight story as to what your judgment is. I’m not concerned about what others think. I just want you to tell me how long you think the South Vietnamese government can stand.”

He said, “Mr. Watts, four to five days at the most.”

“Now, let’s quit playing games,” I said. “I want you to tell me the facts. Where do we stand on the priority list for the evacuation of our people?”

And do you know what he told me? “I can tell you one thing; you’re not on the top of the list.”

“Well,” I continued, “that confirms what I have believed. Now, what about the commitment that the ambassador and his deputy and the State Department gave to our people? We were assured by Deputy Ambassador Lehman that a plan would be devised. We were told that the hospital would be a staging area and that our people would be given high priority because of their close connection with the United States government and the church.”

He said, “I cannot answer that question. That’s not for me to decide. I can tell you that others on the list are far ahead of your people.”

“Then tell me, how are we going to get these people out?” I asked.

He said, “Mr. Watts, I’ll make one suggestion. If I were you at this point, I would not depend on the embassy to work it out for you. You’d better find a way. You’d better find another way.”

We had received word earlier that day that one of the men involved in this whole process had been assigned by President Ford to serve as a liaison in the evacuation. His name was Johnson. Little did I realize at that time that this man was personally acquainted with Pastor Giao. He knew Adventists, and he knew the hospital. He knew much about us. Here again you can see how the Lord leads in all of these things. I was told that I had to find him if we were going to arrange for our people to leave. He was the one to contact.

I left the embassy about ten o’clock that Wednesday night, returned to the hospital, and met with our leaders for a few moments. Then I went back to the airbase where so much was taking place.

During the course of the day, from seven in the morning until eight in the evening, it was difficult even to drive to the airbase. People were flocking out of Saigon by the thousands, standing at the entrance to the airbase, hoping that by some sheer miracle they might make their way through the gates and onto a flight. We were told that at times there were five to seven thousand people standing outside the one entrance into the airport! The airport was heavily guarded with military and government officers, and it had big, barbed-wire barricades. The only way to negotiate your way in was to make a very slow, careful S-turn. Everyone who went through there during the day was very closely scrutinized, and unless they had the proper papers or permits, there was no way to get in. And on the inside, hundreds and thousands were lined up, waiting to get on those flights.

The airbase was a huge military complex. Sometimes it was referred to as Pentagon East! You cannot believe how enormous the complex was inside the staging area. It was also heavily guarded by the U.S. Marines. As we drove in we could see thousands of Vietnamese waiting for the flights to be called so they could board a plane and be on their way.

But not very many of our key leaders were getting on those flights, and time was getting short. We were faced with an enormous obstacle. I never felt so inadequate in all my life as I did at that time. Oh, how we prayed as we worked during the day. Each of us, in our own way, lifted up our prayers to God. “Please, Lord, show us the way! Open the doors. Help us to know what you want us to do. Give us the wisdom and discernment that we need at this critical time. And above all, help us to keep calm, to be patient, to be understanding.”

Some of the missionaries were getting jittery nerves by now, but the morale among our Vietnamese members and workers had reached a terribly low point. They were very discouraged. I’ll never forget a meeting I had with some of the young men of the hospital staff whom I had met just the evening before. We had a rather difficult session. One of the young men stood up, pointed his finger at me, and said, “Pastor Watts, we have lost all our faith in you and in the church. You’re an American. You can go out to that airbase and leave here any time you wish. But what about us? Our lives have been wrapped up with the church leadership, including yourself, that every step would be taken to make it possible for those of us who have laid our lives on the line to leave. You have failed us.”

That was pretty bitter medicine. I was doing the very best I could under those circumstances, and it was hard to listen to those kinds of accusations. But I could understand their frustration. Had I been in their place I probably would have reacted the same way. That’s how tense the situation was. Our people were demoralized. Our leaders were worried sick. They didn’t know what the future held for them.

Our people were demoralized. Our leaders were worried sick. They didn’t know what the future held for them.

It was a Wednesday evening when the chief political officer’s assistant at the embassy told me that we would have to find our own way out of the country. As I left the embassy, I knew that the man to help us find that way was Mr. Johnson, and I had been told that he would be at the defense attaché’s office at the airbase at about ten-thirty. So I quickly made my way over to the airport, and I tried to find Mr. Johnson among the hundreds and thousands of people milling around. The gymnasium had been taken over as a processing center. The bowling alley was now a nursery. Vietnamese mothers with little children packed the twelve-lane bowling alley that had been used as a recreation center until just a few days before. The place was packed with people, and here I was, trying to locate Mr. Johnson.

A short time later, I saw a black automobile pull up. Out of the back seat came a man in his early fifties. I looked at him in the dark, and I thought,

Well, this can’t be Johnson, looking like this. He was wearing a short-sleeved, sweat-stained rumpled shirt. He had two days’ growth of beard, his hair was disheveled, and his pants were all wrinkled. I said to myself, This can’t be the man that President Ford has assigned to do this job. But I went up to him and said, “Are you Mr. Johnson?”

He turned around and said, “Yes.”

I said, “My name is Watts, and I must talk to you.”

“What is it?”

I said, “Are you acquainted with Saigon Adventist Hospital?”

“Oh yes. I know the hospital well.”

“The United States government promised us that it would make provisions for the evacuation of our key Vietnamese people when the time came,” I said. “And Mr. Johnson, we’re convinced that the time has come.” I recounted my visit with the political officer just thirty or forty minutes previously, and then I said, “Mr. Johnson, we are absolutely at our wit’s end. We don’t know where to turn. I have been told that you have been given a special assignment to help out with the evacuation process. Can you help us?”

I had talked with our Vietnamese leaders earlier about a basic number that we could agree on in case authorization came, so when he asked how many I felt would be involved in this evacuation, I said, “Probably not more than 175.”

“Oh,” he said, “We haven’t had a group that large go through yet. There’s nothing I can do tonight. Why don’t you come back to my office in the defense attaché wing at eleven tomorrow morning, and I’ll see what I can do. I just can’t promise anything at this time.”

I said, “Mr. Johnson, all we’re asking is that you do what you can for us.”

He said, “I’ll do what I can.”

He left, and we left.

It was now about eleven o'clock Wednesday night. I went back to the hospital and asked Pastor Giao to call a number of our Vietnamese leaders together. Seven or eight came, and we met in Mr. Rudisaile’s office. I turned to Pastor Giao and said, "Pastor Gaio. I want to tell you exactly where we are.” “After I gave him an up-to-date report, I said, "Now I’m going to give you the most difficult assignment you have ever had."

He said, "What is it?"

"By eight tomorrow morning I want a list of 175 people who should leave the country."

Pastor Giao just shook his head. I'll never forget it. He said, “Pastor Watts, you’re asking us to be like God. You’re asking us to decide who's going to live and who's going to die."

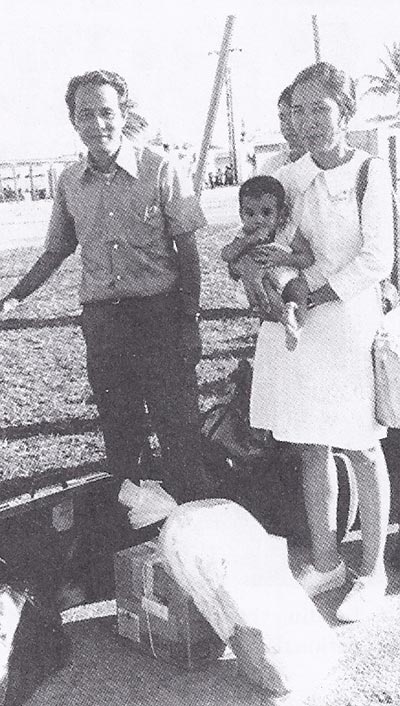

Saigon Adventist Hospital: Given to the Seventh-day Adventist Church by the U.S. Army, the hospital was known among the military community especially in the final days of the war. Credit: LLU/Ralph S. Watts" class="img-left"> I said, "that’s right. None of us as expatriates should make this decision. We can’t do it. lt is not our responsibility. That’s why I have called you men together. You’re the ones who must decide. I want you to weigh it very carefully. ln your judgment, decide whose lives would be endangered the most if they were to remain behind. Who should have first priority to leave? I want those names on a Iist. And furthermore, Pastor Giao, I want you to include in that list the employees of our hospital who are not Adventists. We have just as much of a moral obligation to those not of our faith who are working with us in our institutions as we do our own people. They stood by us faithfully. You need to keep them under consideration as well. Pastor Giao, I need that list by eight in the morning."

Saigon Adventist Hospital: Given to the Seventh-day Adventist Church by the U.S. Army, the hospital was known among the military community especially in the final days of the war. Credit: LLU/Ralph S. Watts" class="img-left"> I said, "that’s right. None of us as expatriates should make this decision. We can’t do it. lt is not our responsibility. That’s why I have called you men together. You’re the ones who must decide. I want you to weigh it very carefully. ln your judgment, decide whose lives would be endangered the most if they were to remain behind. Who should have first priority to leave? I want those names on a Iist. And furthermore, Pastor Giao, I want you to include in that list the employees of our hospital who are not Adventists. We have just as much of a moral obligation to those not of our faith who are working with us in our institutions as we do our own people. They stood by us faithfully. You need to keep them under consideration as well. Pastor Giao, I need that list by eight in the morning."

Pastor Giao and his group gathered around the table while I tried to get a few hours of rest. I’m sure there were a lot of tears shed. There was a lot of soul searching, a lot of agony. What family stays? 'What family goes? They knew that those who were asked to stay might very well lose their lives. How would you like to have to be faced with that kind of a decision? I’m telling you, my heart went out to Pastor Giao and to my Vietnamese brothers who had to make those decisions as they wrestled in prayer that night, asking God to give them wisdom. Throughout the hours of that morning they labored with that decision.

About five o'clock in the morning, when I had been asleep maybe three hours, there was a knock at my door. In a stupor I tried to awaken. I tried to pull on my clothes, and you know the safari suit is all I had. I pulled on my trousers. I don't even think I had my shirt on when l went to the door, and there was a little Vietnamese lady I recognized. She was our child evangelism director at the mission office. She burst into tears and grabbed my hand. With tears streaming down her cheeks she looked into my face and said, "Pastor Watts, my children, my children. Won’t you please, please help me get my children out so they'll be safe?"

At five o’clock in the morning I had no assurance to give her. We had not received any confirmation yet that we could get any of these people out. But she held on, clutching my arm, weeping. And all I could do was say, "Bach, we will do our best. We will do our best. l'm sure that God will find a way." She left and went back to her family, but I couldn't go back to sleep. My heart was heavy. My mind was racing.

At eight o'clock I went to the office, and there were Pastor Giao and several others. Their eyes were bloodshot, and they looked very haggard.

I said, "Pastor Giao, do you have the list for me ?"

He handed me a manila file folder. I took the folder, opened it and began turning the pages. One page, two pages, filled with Vietnamese names. I recognized some of them. Four pages, five, ten, twelve pages. I began to get a little suspicious. Closing the folder, I turned to Pastor Giao and said, "I need to know something. How many names are on this list?" He didn’t want to answer. He said, "Pastor Watts, we did what you asked us to do. You asked us to give you a list of names." I said, "Pastor Giao, that's not what I’m asking you now. I want to know how many names are on this list." I was beginning to get a little upset.

Pastor Giao dropped his head, and then he looked at me. Tears welled up in his eyes and he said, "Pastor Watts, you'll never know what we experienced during the night. Over and over and over we went as we considered these names."

"Pastor Giao, how many names?"

He said, "Pastor Watts, we did the best we could. We tried to reduce it down to the figure you gave us."

"Pastor Giao, how many names?"

"Pastor Watts, there are 225 names on that list."

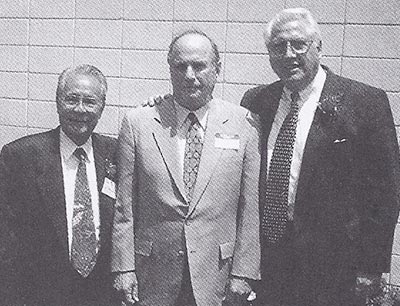

God's Man: Mr. Johnny Johnson (center) was God's man in the right place at the right time. Pastor Giao and Pastor Watts join him on the left and right, respectively." style="font-size: 16px; float: right;" class="img-right">I said, "What do you expect of us? We’ve gone to Johnson. I have asked that possibly 175 be considered. He said that's the largest group that's ever been considered up to this point outside of embassy people. How can we in good faith go back now and tell him that we've changed that from 175 to 225? I don't know what you expect of us. We’re doing everything we can."

God's Man: Mr. Johnny Johnson (center) was God's man in the right place at the right time. Pastor Giao and Pastor Watts join him on the left and right, respectively." style="font-size: 16px; float: right;" class="img-right">I said, "What do you expect of us? We’ve gone to Johnson. I have asked that possibly 175 be considered. He said that's the largest group that's ever been considered up to this point outside of embassy people. How can we in good faith go back now and tell him that we've changed that from 175 to 225? I don't know what you expect of us. We’re doing everything we can."

And then Pastor Giao, bless his heart, gave me a little sermon.

He said, "Pastor Watts, let me ask you one question. Do you remember the worship that you had yesterday morning? Do you remember that passage of scripture that you read to us? ‘Behold I am the Lord, the God of all flesh. Is there anything too hard for me?’ Pastor Watts, all we’re asking is please, please try.”

Now how would you answer that kind of appeal? I took the file folder, put it my case, and left.

Several of us were at Mr. Johnson’s office at eleven o’clock that morning. l'll never forget the experience of going clown those corridors. Have you ever walked through a large office when it was completely deserted? That’s the experience. We walked down the long, narrow corridors, and we went to the left, and we went to the right. The corridors were filled with crates. The shredding machines had done their work. The files were empty. And there was shredded paper all over the place. Most of the office was empty. The building was virtually deserted, except for the few who were working to the last.

When we arrive at Mr. Johnson’s office, we found a note pinned to the door. It said, “Am out of the office. Will not be back until 1:00 p.m.” So we left. At one o’clock we came back. About one-thirty Johnson appeared, and he hadn’t changed clothes from the time I’d seen him the night before. He looked just as bad. Here was a man who was working around the clock, trying to save lives. I admired and respected him for it. He was putting aside personal comfort and east for the sake of the people.

He came down the corridor, walked past us, and asked us to

follow him. We walked into his office, and he sat down behind his desk. I can picture him now, sitting there. His desk was placed at a catty-corner angle to the rest of the room. He sat down at his desk, leaned back, put his hands behind his head, and tried to stretch and sigh and rest a little bit. Then he said, “All right, do you have your list?”

I handed him the file folder. He took the folder and laid it down on his desk. Then he opened it and began turning the pages. My heart seemed to beat loudly. He turned the pages. He didn’t say anything; he just looked at the list, mulling it over. Finally, he closed the folder, looked up, and said, “How many names do you have here?”

I said, “Mr. Johnson, I’m embarrassed, but I have to tell you; early this morning I gave explicit instructions to our Vietnamese leaders that they were not to have any more than 175 names on that list. But when I talked to them several hours later, they shared with me the predicament that they were faced with.”

“How many names are on the list?”

I swallowed hard and said, "Sir, there are 225 names on this list.

l'll never forget it. He shook his head, placed the palm of his

hand on his forehead, and said, “Gentlemen, I don’t know if we can do this. I can tell you one thing. I don’t have the authority to authorize this large a group to leave.”

I said, "What do you have to do?"

He said, “I’ve got to go upstairs and talk to the general and his staff. I’ll probably have to contact the embassy, and possibly even the State Department and the Pentagon.”

I said, “Mr. Johnson, whatever you have to do, please, please do your best for our Vietnamese people.”

He stood up.

“What time do you think we ought to be back?” I asked. “How long will it take?”

He said, “I have no way of knowing. Why don’t you come back about three o’clock. I’ll go right up and see if I can get an interview and make this case for you.” Then he left.

Some of our group went back to the hospital; some of us stayed. We would all have left and come back, we were worried about what would happen if Mr. Johnson needed further information and no one was there to talk to him. So some of us decided that, much as we didn’t want to stay, we ought to. For those of us who stayed behind, that two-hour interval was the longest period of time that we can ever recall, because the lives of so many people were in the hand of so few. We paced those quarters. As close as we were friends and colleagues, each of us was so immersed in his own thoughts that we hardly even talked to one another. We prayed, pleading with God. We paced back and forth through those empty corridors. You could hear the echo of our footsteps as we walked back and forth, wondering what would be the outcome of our cry for help in this great hour of need for our people.

Today: Ralph Watts will never forget Vietnam and its people and will travel there in a few weeks to continue ministering to Adventist believers there." style="font-size: 16px; float: left;" class="img-left"> Three o’ clock came. Johnson was nowhere to be seen. Three-fifteen, still Johnson didn’t show up. Our anxiety was growing. Finally, at about three-thirty—I’ll never forget it, because I looked at my watch—I heard footsteps coming down from the upper floor. And down the steps came Mr. Johnson. I looked into his eye to see if I could get an answer, but his face was totally expressionless. He walked right by us. And we followed him. He went up to his office, took out a key, opened the door, went inside, and sat down. We followed right behind him and stood right there at his desk. We didn’t even sit down.

Today: Ralph Watts will never forget Vietnam and its people and will travel there in a few weeks to continue ministering to Adventist believers there." style="font-size: 16px; float: left;" class="img-left"> Three o’ clock came. Johnson was nowhere to be seen. Three-fifteen, still Johnson didn’t show up. Our anxiety was growing. Finally, at about three-thirty—I’ll never forget it, because I looked at my watch—I heard footsteps coming down from the upper floor. And down the steps came Mr. Johnson. I looked into his eye to see if I could get an answer, but his face was totally expressionless. He walked right by us. And we followed him. He went up to his office, took out a key, opened the door, went inside, and sat down. We followed right behind him and stood right there at his desk. We didn’t even sit down.

He took that file folder and handed it back to me, and I just knew that it hadn’t worked out. I asked, “Mr. Johnson, what was the decision?”

He handed me a piece of paper. “I have a letter for you. Read it.”

And here is that letter:

Embassy of the United States of America

Defense Attaché Office

24 April 1975

To whom it may concern:

The attached manifests are dependents of individuals who have closely associated with the United States government. Because of this close association with us, their lives may be in danger.

H.D. Smith, Jr.

Major General, United States Army

Major General Smith. That was the same general who less than three weeks earlier had sent us a letter of appreciation!

I put the letter in the folder. “Does this say what I think it says?”

“Yes, it does, Mr. Watts. Your request has been approved.”

I could have leaned right down and hugged him! You will never in your imagination understand the load that was lifted from my shoulders at that time. We looked at one another and smiled, and we left that office praising God for what had been done.

We found out later that when Mr. Johnson went into see General Smith, he said, “General, I have a very important request to make of you.”

“What is your request?”

“Do you know about Saigon Adventist Hospital?”

The general said, “Why, of course I know about that hospital.”

“General, I believe that we owe those people something for what they have done for us over the years.”

And the general said, “I agree. What’s your request?”

Johnson explained our need. They contacted the embassy and the United States government. Word came back giving clearance for everyone on that list to leave.

But in the end, 225 people didn’t leave Vietnam—410 did. They left their country on eight flights before the airport was totally shut down, making helicopter and boat evacuations the only viable way out. Loma Linda University then guaranteed all 410 evacuees, and following their arrival from Saigon and Guam to Camp Pendleton in California, they were housed and cared for on the campus until further arrangements for their new life in America could be made. Watts was there when they arrived—seeing through an unbelievable exodus that has now resulted in a strong base of Vietnamese Seventh-day Adventists in North America.