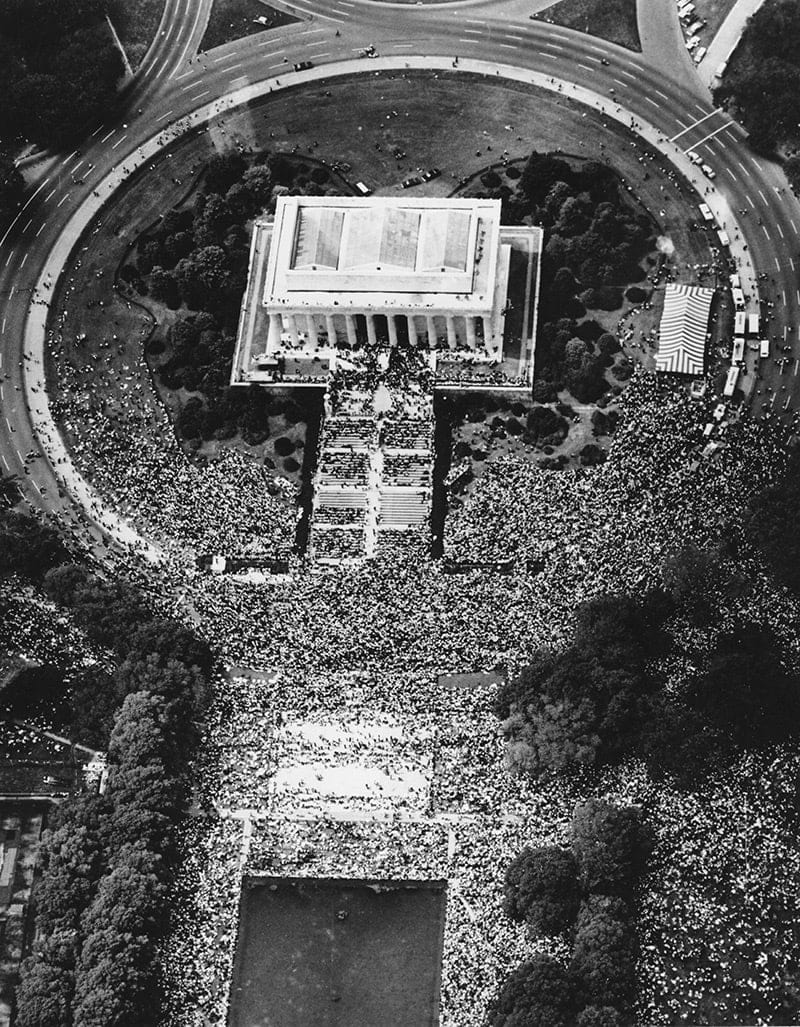

A Seventh-day Adventist woman can be spotted on stage beside Martin Luther King Jr. during arguably the most pivotal event of the civil rights movement — his “I Have a Dream” speech to a crowd of 200,000 to 300,000 people in Washington in 1963.

But who is she?

Yolanda Clarke, who will turn 90 in a few months, says her presence on the stage is a testament to the power of God to help African Americans and a reminder to Adventists that they must, like Jesus, actively engage in the world around us.

This is the message that Clarke wants to convey to fellow Seventh-day Adventists as the United States celebrates Black History Month in February.

“I would stress two things,” she said in an interview. “First, we as African Americans need to remember that the only thing that has helped us as a people to survive and prosper in America is God’s unchanging hand. It has been our relationship with God that has gotten us through.

“And No. 2, we as Adventists are too withdrawn from what’s happening around us. We must change that. Jesus was among the people — that’s where His ministry was. And so we also need to be a part of what’s going on. That’s the only way our light will shine.”

Clarke’s road to the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom provides a glimpse of God’s leading in her life.

Yolanda Clarke was born in Asheville, North Carolina, in 1925, several years before the Great Depression. Her father, A. Wellington Clarke, of Kingston, Jamaica, was an early black Adventist minister. Her mother, Jennie Josephine (nee Bowman) Clarke, of Lawrence, South Carolina, was a trained pianist and music teacher.

Yolanda’s early life was filled with music and happiness. Although the Clarkes were poor, Yolanda and her four siblings never knew it.

“Even though we were raised in the midst of the Depression, we had none of the apprehensions you may have if you were accustomed to having a whole lot,” Clarke recalled. “That we were poor never even entered our minds.”

But among the few furnishings the family did have was a piano, and Yolanda learned to play at a young age. After her family moved to Boston, she played on one of the city’s radio stations at just 14 years old.

Groomed for a career in music, Clarke studied at some of the most prestigious schools in the world: Boston Conservatory, New York University, Columbia, and the Royal School of Music in London. In 1948 she graduated from NYU. In fact, all five of the Clarke children graduated from college, a significant feat during an era when African Americans were often denied higher educational opportunities.

As a young musician in New York City, Clarke had a hard time finding work.

“I was eminently qualified but was often turned down because of the color of my skin,” she said.

However, Clarke possessed a determination that was greater than any setbacks. She took jobs playing the organ at churches across the city, and in no time her undeniable musical talents were in demand. Although her membership was at the Ephesus Seventh-day Adventist Church, she performed at renowned churches such as St. Patrick’s Cathedral and Abyssinian Baptist Church.

“There were members at Ephesus who thought that I shouldn’t play for Sunday churches,” she said with a smile. “But whatever I did I was going to shine for Jesus.”

Clarke did indeed shine. She became known in circles as a Seventh-day Adventist who held distinctive beliefs yet was totally friendly and down-to-earth.

“I am an SDA through and through,” she said. “Been one my whole life. Everybody learned sooner or later what I believed. At times they’d tease me about not eating meat or drinking alcohol, or going to church on Saturday, but they always respected me. I know it was a positive witness.”

It was during this time in Yolanda Clarke’s life that she became especially interested in civil rights. She was drawn by the example of Adam Clayton Powell, a Christian minister who was the first African American to win a seat on the New York City Council and the first black New Yorker to be elected to the U.S. House of Representatives.

“Abyssinian Baptist Church,” the church Powell pastored, “was in the middle of a black area, yet they didn’t hire blacks in the stores and businesses there,” Clarke said. “Powell did all he could to get blacks hired, protesting and boycotting. It worked. Soon blacks were being hired.”

Clarke recognized that civil rights was not just a black issue, but a human issue.

“Every human being should be afforded basic human dignity,” Clarke said. “You should never sit back while this is pushed aside.”

Several times during the 1950s Clarke recalls that one of her friends invited her to meals with a young Baptist preacher and his wife, active in the civil rights movement, Martin and Coretta King. But she never had time.

“My schedule was so full back then,” she said with a laugh. “It just never worked out.”

But as the 1960s dawned, the charismatic preacher from the South was becoming a household name, and was stirring the conscience of the nation with his prophetic calls for social justice.

“During those years I had been impressed to pray for Dr. King daily,” Clarke said. “I believe that every once in a while God raises up an individual to set the nation straight and King was that man.”

Clarke was the music director at Union United Methodist Church in Brooklyn, New York, when she first heard of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, to take place on Aug. 28, 1963. She pined for an opportunity to go, but nothing presented itself.

That is until a couple of weeks before the event. Eva Jessye, a larger-than-life musician in New York City who founded and directed the legendary Eva Jessye Choir, wanted Clarke to join them to perform at the March on Washington. It was to be the official chorus for the event.

“I jumped at the opportunity,” Clarke said.

And so at 4 a.m., Wednesday, Aug. 28, while it was still dark outside, Yolanda Clarke and the other choir members loaded into a Local 802 bus in downtown Manhattan. The trip took much longer than usual, as traffic was bumper to bumper from New York to Washington. But the bus was filled with an electricity.

“It was the most thrilling thing you’d ever want to be involved in,” Clarke said of that morning. “It’s impossible to describe. Over 50 years ago, and it’s still like yesterday.”

All along the way supporters stood beside the road, often entire families, with kids holding up signs that read, “Go to Washington and tell ’em for us!”

When the Eva Jessye Choir arrived on the grounds of the Lincoln Memorial and filed out of the bus, the air seemed charged with meaning and possibility. The choir members were given passes to be on the dais. When Clarke ascended the steps of the Lincoln Memorial and looked out over the tens of thousands assembled on the lawn and on either side of the Reflecting Pool all the way to the Washington Monument, she was in total awe.

“Being on the dais was one of the most marvelous experiences of my life,” Clarke said simply, words failing her.

Interestingly, Clarke ran into another Adventist on the dais shortly after she arrived. Dickie Mitchell, an Oakwood University graduate, was there to play the organ for Mahalia Jackson, who was scheduled to sing shortly before King spoke.

“We chatted about what we were both a part of,” Clarke said, “then expressed disappointment that an Adventist minister wasn’t there among the ministers of other Christian denominations to represent our church.”

But an Adventist minister who later served at both Washington Adventist University and Newbold College, Gordon Barnes, was on the dais, only about 10 feet (two meters) from King. Other Adventist ministers, though not on the dais, were present in the crowd.

When the program began the National Mall had filled up with people from every corner of the nation — young and old, men and women, of every race. As the members of the Eva Jessye Choir were preparing to perform, Jessye pulled Clarke aside and told her that she needed her on the organ, and not singing with the choir.

“I was disappointed at this, because I wanted to sing in front of all those thousands of people,” Clarke said.

But little did she know that her reassignment would put her at the center stage of history.

Clarke expertly played the organ for the songs "We Shall Overcome" and "Freedom Is The Thing We're Talking About." The large audience joined in with the Eva Jessye Choir, the swell reverberating across the Mall.

See a copy of the program for the 1963 event

When the songs were finished Clarke rose from the organ, which was a dozen or so feet (about two meters) behind the podium. The choir members had been assigned seating in the front row of the audience, and Clarke tried to negotiate the considerable throng on the platform between her and her seat. On the way Clarke intermittently paused for prayer, circled groups, and listened with admiration to Mahalia Jackson sing “How I Got Over.” By the time King was introduced and had risen to the podium, Clarke had broken through the crowd — and found herself standing just feet away from King.

“I did not realize how close I was to Dr. King until everyone told me later that they had seen me next to him on TV,” Clarke explained. “The only person between us was the park ranger,” Gordon Gundrum.

And of King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, which has become one of the most legendary in American history?

“I was enthralled by Dr. King’s speech. Everyone was spellbound,” she said.

Intriguingly, the part of the speech that is most well-known was not in the script that King held that day. Clarke was a first person witness as to how King came to utter those memorable words.

“When Dr. King appeared to be nearing the end of the speech, I heard Mahalia Jackson say, ‘Tell ‘em about the dream, Martin.’ And then Dr. King told us about that dream,” Clarke said.

In fact, King had employed variations of “I Have a Dream” before, including at Oakwood University about a year and a half earlier. But the dream King conveyed that day before the gigantic statute of Abraham Lincoln to the hundreds of thousands on the National Mall, and the still many millions more watching on television, was to be immortalized in history. The footage of the speech shows Yolanda Clarke wiping tears from her eyes at King’s powerful words.

“I teared up because it was so beautiful,” she said. “To look out over the cause of freedom. This was a culmination of the marches in Selma and other cities, the jailings, the bombings, the hoses, the dogs, the sit-ins. … It was breathtaking.”

When King concluded the speech with “Free at last, free at last, Thank God Almighty we are free at last” to deafening applause, he was escorted away, leaving Yolanda Clarke to ponder what had just taken place.

“After the speech was over I just stood there and watched,” she said. “I felt that God was using everybody that was at that March to speak for all of those people who couldn’t speak for themselves—the Africans who died on the Middle Passage, the blacks who were enslaved, the poor who had no voice. It takes everybody — from the lowest to the highest — to bring to focus the things that are vital to humanity.”

“Tell ’Em About the Dream,” a 2013 editorial by Bill Knott

"A Journey and a March," a 2003 cover story by Bill Knott