, chair, church history department, Andrews University

A

s a doctoral studies student in the early 1960s, Herbert E. Douglass was assigned coursework in which he and fellow students at Pacific School of Theology in Berkeley, California, were supposed to read and discuss modern theologians.

Several times the class pondered the seemingly intractable contradictions between leading theologians and Douglass offered an insight that the whole class recognized as clarifying the difficulty.

At first classmates thought Douglass was just theologically gifted. But as the pattern recurred, several came to him and said, “You must be getting these insights somewhere. What are you reading besides the class assignments?”

In response, Douglass pointed them to the writings of Seventh-day Adventist Church co-founder Ellen G. White. One of his classmates, after reading White’s Desire of Ages, said, “I see what you mean. This author has a self-authenticating quality.”

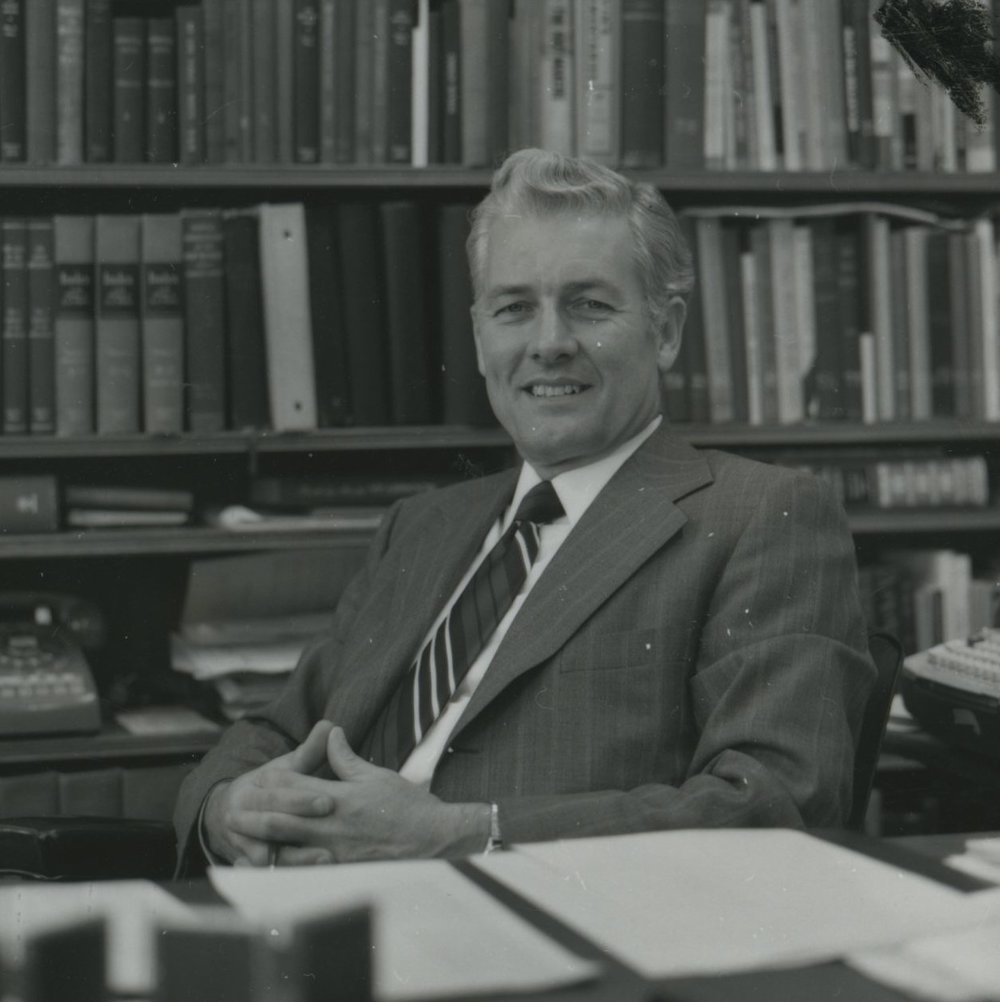

Douglass, who shared this incident with me in personal conversations and e-mails, put White at the center of a theological system that he built over his lifetime. He reasoned that if Adventism is true, and if White was used by God to aid in the development of a genuinely biblical theology, then White’s writings should contain the necessary insights to solve any problem. To understand her writings at a deep level became a pursuit that only ended with his death after a long illness on Dec. 15 at age 87.

Appreciating the passion that Douglass, a 20th-century leading theologian of the Adventist Church, had for White requires an understanding of the turbulent world of Adventism that he entered as a young pastor in the 1950s.

Let me explain.

A core value that Adventists inherited from the Protestant Reformation was the idea that because of human complacency and backsliding, the only way for a church to stay reformed was to be always reforming. The flaw in every religious movement was to consider itself “reformed” and to cease the ongoing process of “reforming.” White repeatedly asserted, “We are reformers,” and early Adventists saw their mission as completing the Protestant Reformation in preparation for the coming of Jesus.

A major objection to church organization in the 1850s was that it would bring an end to ongoing reformation. Adventist pioneer and White’s husband, James, countered that the gift of prophecy was the divinely provided agent for the continual reformation of the church.

Indeed, Adventist history could be considered as the story of the conflict between sinful human nature and God’s call to a completed Reformation, culminating in the latter rain of the Holy Spirit that would finish the gospel to the world.

Unfortunately, in the 1860s and 1870s, several leading evangelists relied on doctrinal debate to the neglect of a personal relationship with Christ, producing church members who, like themselves, were convinced of correct doctrine, but not converted to an intimate daily relationship with Jesus.

By the 1880s Adventism had a desperate need to rediscover the living experience of righteousness by faith in Jesus Christ alone. The 1888 conference was a needed corrective, but personal animosity and theological rivalry hindered the work God designed to accomplish. In 1892 Ellen White wrote that “the loud cry of the third angel has already begun in the revelation of the righteousness of Christ,” but by 1896 she concluded that Satan had largely “succeeded” in preventing that message from accomplishing the work God had designed it to do.

Thus Adventists entered the 20th century deficient in understanding the righteousness of Christ, but mostly unaware of the deficiency. They were regarded by most other Protestants as a legalistic sect if not an outright cult.

The 1950 General Conference session attempted to remedy this by a call to revival and reformation, but based on a merely legal view of justification, not the entirely “new creation” envisioned by Paul in 2 Cor. 5:15-17 and endorsed by White.

Two young Adventist missionaries to Africa protested this deviation, and church leadership felt under attack. An external pressure point for Adventist leadership emerged in 1955 when some evangelicals confronted Adventists as being less than orthodox Christians. This led to the publication of a new book, Seventh-day Adventists Answer Questions on Doctrine, in 1957 by Review and Herald.

Questions on Doctrine states upfront that its goal is “not to be a new statement of faith,” but to explain Adventist “beliefs in terminology currently used in theological circles.”

But the issues raised by the book soon polarized the denomination. L.E. Froom, a major contributor to the book, wrote later in a 1971 book, Movement of Destiny, that he saw Questions on Doctrine as a “providential” opportunity to correct “the distorted caricature of our faith” and mend “the impaired image of Adventism.”

On the other hand, M. L. Andreasen, a theology professor recently retired from the Adventist Seminary at the time of the publication of Questions on Doctrine, denounced the book as "apostasy" in a series of open letters to the whole denomination.

Before 1957, self-supporting ministries within Adventism were privately funded local organizations focused on health or educational outreach. But the Questions on Doctrine controversy gave rise to a new breed of independent ministries that were not primarily focused on outreach but on theological controversy.

Into this volatile situation came the young Adventist minister Herbert E. Douglass. His ministry would span more than 60 of the most turbulent and controversial years in Adventist history.

In 1953, Douglass was 26 with six years’ pastoral experience when Pacific Union College called him to teach and then sponsored him to the Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary.

In those days, the seminary, the General Conference headquarters, and the Review and Herald publishing house stood side by side in Takoma Park, Washington, D.C. As Douglass became recognized as an unusually gifted scholar, the Review and Herald invited him to join the editorial staff preparing volumes 6 and 7 of the Seventh-day Adventist Bible Commentary. Thus he had a ringside seat for observing the developing controversy.

In 1957, the year Questions on Doctrine was published, Douglass graduated from the seminary and returned to teaching theology at Pacific Union College.

One of the doctrines at the center of the book debate concerned the relation of Christ’s work on the cross to His work in the heavenly sanctuary. Questions on Doctrine defined the atonement of Christ as “finished at the cross” and the high priestly ministry of Christ as merely “applying the benefits” of the atonement completed at the cross. The practical effect of this teaching was to emphasize present salvation and assurance, but to de-emphasize the sanctuary truth that the ultimate completion of the atonement includes eradicating every trace of sin from the universe.

On the other hand, some opponents of Questions on Doctrine tended to give the impression that because the high priestly ministry of Jesus is not yet ended, believers cannot expect to have present assurance of salvation. (This would be, of course, directly contrary to Hebrews 7:25, which bases the certainty of salvation precisely on the fact of Christ’s continuing intercession.)

The truth is that both Christ’s sacrifice on the cross and His subsequent high priestly ministry are absolutely essential to the plan of salvation; emphasizing either to the exclusion of the other is heresy.

Another doctrinal debate opened by Questions on Doctrine concerned what kind of humanity Jesus possessed during the incarnation. In Jesus, the Benchmark of Humanity (1977), Douglass and co-author Leo Van Dolson argued that Jesus was not only God but also man—fully man, though never sinning.

Douglass early recognized that merely arguing over the atonement or the nature of Christ was too narrow a focus to address the real problem. The greater problem was the fundamental clash between the presuppositions of evangelical Calvinism and the Adventist form of Arminianism. Douglass likened this clash to the tectonic plates of the earth’s crust, which, when they collide, produce an earthquake. But this insight alone could not resolve the issue either, for the Calvinist-Arminian debate is 400 years old and perceived by many as a hopeless stalemate.

Douglass turned to Ellen White for solutions to the deepening divisions in Adventism. He continued his search of White’s writings after he became chair of the theology department at Atlantic Union College in 1960; as a doctorate student at Pacific School of Theology, where he graduated in 1964; and when he returned to AUC as its academic dean and later president.

He was at the college in 1970 when Kenneth Wood, editor of the Review and Herald (now the Adventist Review) invited him to become an associate editor of the general church paper. This gave Douglass the time and opportunity to publish articles and books on the concepts he had developed during his years of teaching. Besides hundreds of articles, he eventually produced some 30 books on eschatology, the sanctuary, faith, assurance of salvation, perfection, the nature of Christ, the life and ministry of Ellen White, and the Adventist health message. His textbook, Messenger of the Lord (1998) was the most comprehensive volume on White prior to the Ellen G. White Encyclopedia (2013), for which he was also a major contributor.

Douglass found the starting point for his theology in the biblical narratives of the conflict between good and evil, and in White’s comments on those narratives. The inception of sin, Satan’s charges against the character of God, and the unfolding of God’s plan of salvation as the comprehensive answer to all Satan’s charges, exposed the weaknesses in most modern theologies.

White’s focus on the character of God as the fundamental issue in the great controversy became the foundation of Douglass’ theological system. He was not the only Adventist theologian contributing to this development, nor was he the only one to use White’s great controversy theme in this way, but for 40 years he issued an almost constant stream of publications, building and elaborating his theological system.

The great controversy theme clearly exposed and resolved the false dilemma between Christ’s work on the cross and His work in the heavenly sanctuary. As the purpose of the atonement was to heal the estrangement that sin had created within the universe of God, it was clear that the cross was the center, but not the end of the atonement. Christ’s sacrifice on the cross was perfect, complete, sufficient, and once for all. But on the morning of Christ’s resurrection, there was still unfinished business in the universe that only He could accomplish.

The most comprehensive presentations of Douglass’ theological system are found in two books published rather late in life: God at Risk: The Cost of Freedom in the Great Controversy (2004) and The Heartbeat of Adventism: The Great Controversy Theme in the Writings of Ellen G. White (2011).

In short, Douglass was a giant, a legend in his own lifetime to thousands of Adventists who read his writings and applied his insights to their daily lives. Whether he was right will continue to be debated. But even those who disagree with him can scarcely dispute that through his writings he will remain one of the most influential Adventist theologians of the 20th century.

Adventist Review, Dec. 17, 2014: "Herbert E. Douglass, Leading Theologian and Author, Dead at 87"