Takoma Park, the Azalea City, has been the host and hub of key Seventh-day Adventist institutions for more than a century. These include the church’s world headquarters and several academic and health institutions. Relationships between city andinstitutions have not been static.

First incorporated in 1890, Takoma Park, Maryland, was a region of the District of Columbia and the state of Maryland until 1949, when some of it became a Maryland municipality while the rest continued as a neighborhood in the national capital.1 Entrepreneur Benjamin Franklin Gilbert developed the community by creating housing for the growing federal bureaucracy. At the turn of the century the community’s rural air appealed to people employed in the city who loved the gentle hills, gurgling streams, and woodlands of less-urban places.2 For attractions such as these, Takoma Park was selected as the location for the headquarters of the Seventh-day Adventist Church.3

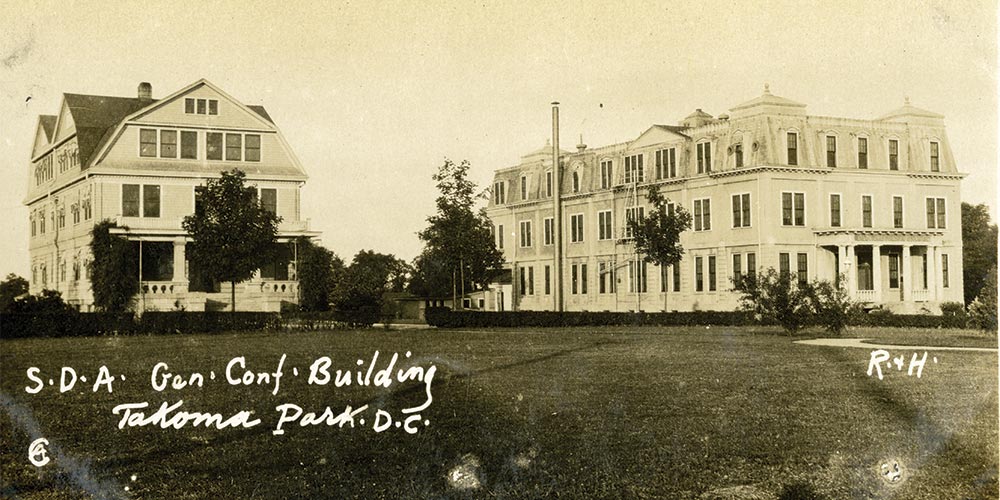

In the main it has worked out well.The initial four Adventist institutions established in Takoma Park beginning in 1904 included the General Conference, the Washington Training Institute (now Washington Adventist University), the Washington Sanitarium and Hospital (now Washington Adventist Hospital), and a secondary school included as part of the Washington Training Institute (now Takoma Academy), as well as a church.4 Throughout much of the twentieth century, relationships of these institutions to the rising Takoma Park community have been pleasant, as community values were generally in accord with Seventh-day Adventist values on healthful living.5

Adventists choose to remain in the community as a matter of loyalty.

Beginning in the late 1950s and early 1960s, five significant changes in the community particularly impacted its Seventh-day Adventist institutions.First, in the late 1950s, the diversity of the District of Columbia and Maryland Takoma Park community increased, largely as the result of school desegregation driven by the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision of 1954. Community diversity was also significantly impacted by the displacement of a massive number of African Americans to make way for the Southwest Freeway in another quarter of Washington. The community’s existing White residents and newly arrived Black residents on both sides of the boundary came together in Neighbors, Inc., a community-based organization determined to create and sustain racially integrated neighborhoods.6

Second, beginning in the 1960s, a complex of social reform movements made Takoma Park attractive to counterculture “hippies” and the communes they inhabited. Groups of predominantly young White social reformers secured large houses in Takoma Park at favorable prices, as they sought alternative and often controversial ways of living together that varied decidedly from traditional Adventist values. Third, in the 1970s, the increase in gasoline prices brought “yuppies”—young urban professionals—to Takoma Park, who ordinarily would have lived further out in the Washington, D.C., suburbs. This further changed community composition away from Seventh-day Adventist norms.

Fourth, also beginning in this period, many came to find refuge in Takoma Park from non-European war zones. Fifth, in addition to these demographic changes in race, ethnicity, culture, and values, the community became an Eastern focal point for progressive, even radical, politics. Initiated by the successful objection to a freeway that would have eviscerated the community in connecting the Washington Beltway with downtown Washington, the Takoma Park community became radical in a way not resonant with Adventist norms.7

Washington Adventist Hospital now serves a great many more people of color, and of the medically indigent, than before. Once Caucasian, Washington Adventist University is now more than 80 percent populated by people of color.8 Takoma Academy is now home to 79 percent students of color.9 As Adventists moved their world headquarters in 1989, Takoma Park was a changing urbanized landscape. Once a calm, socially conservative community, predominantly European American, Takoma Park has become a vigorous, radical community, a nuclear free zone, a sanctuary city for undocumented residents, and a place where 16-year-olds and undocumented residents may vote in local elections.

Healthy tensions sometimes appear in the give-and-take between the community and its Adventist institutions as Adventists continue to love and live in a changing community that is still very much their own.

Adventist movement continues, with Washington Adventist Hospital scheduled to open its new site in nearby Silver Spring in 2019. But university, academy, elementary schools, and churches remain in the community to bear their incarnational witness of the gospel to a new set of neighbors through life-affirming values that will never be out of date.

William Ellis, a senior social scientist and public policy analyst, teaches history at Washington Adventist University.