During the Siege of Boston in 1775 in the early days of the American Revolution a battle was fought at Bunker Hill, in the Charlestown section of Boston, Massachusetts. Colonialist militia were overrun by British forces as they attempted to hold fortified lines across the Charlestown Peninsula. While an initial victory for the Redcoats, it didn’t come without heavy losses for their side, exposing the grit and mettle of these new “Americans,” furiously intent on gaining their freedom.

We know how the story ends, for many of us live in its end result: The United States of America, “the land of the free, and home of the brave.”

However, on November 14, 1977, more than 200 years later, the site was again the scene of violence. It was not of the variety that would secure a place in history as a source of national pride, but asked the question of how far these United States had evolved in the quest for freedom and equality for all its people.

Charles Battles was a young, passionate history teacher at Pine Forge Academy (PFA), a historically Black boarding high school in Pennsylvania operated by the Allegheny East Conference of Seventh-day Adventists. In his second year of teaching at the school, he had just finished a unit on the American Revolution. His students—Vivian English, Jennifer Jimerson, Darlene Jones, John Jones, Glenda Lewis, David McDonald, Yvonne Nurse, Sam Perry, Shirley Sims, Andrea Sumpter, Fred Walters, and Mark Washington—realizing their Philadelphia-area campus was just one fun road trip away from the historically significant sites of Boston—asked if they could take a weekend field-study trip. He agreed, got permission from the school, contacted a local church to house them, and had all the students raise the money they needed to make the journey (about $35 in those days).

The next Sabbath morning, the group of 14—including Battles and his wife, Miriam as chaperones, arrived at Boston's Berea Seventh-day Adventist Church. After enjoying Sabbath services and a meal, the group did a little sightseeing in the afternoon and dove in deeper on Sunday. It was a fun trip to that point; so fun, the kids begged to stay one more day, as there was still much more to see. After calling then-principal Auldwin Humphrey for permission to extend their stay, the group looked forward to touring the Bunker Hill monument on Monday.

That morning the group walked the famed Freedom Trail. After lunch the plan was to visit the Bunker Hill monument before departing for Pine Forge. To access the site, you had to travel to Charlestown, where the monument was located, by city bus.

The group had no way of knowing what was to come and why.

In the early 1970s Boston was the scene of racial tension stemming from court-ordered mandatory school desegregation, or “busing." The decision was not well received. Black students living in Roxbury, for example, were now bused to South Boston, a predominantly White enclave of the city. On arrival at their new school, some students were met with jeers, threats, foul language, and rocks—thrown at them by kids and parents alike. Other families simply refused to comply and boycotted school altogether.* It was well known to most Bostonians what neighborhoods were off-limits to whom, as the racial tension continued into the late 1970s, even after the new school district zoning was well in place.

But for this group of knowledge-hungry teens from a Northern boarding school, this was not the Deep South of the 1950s and 1960s. Boston was a modern city with American history coursing through its veins. How could anything go wrong?

Battles remembers the bus driver repeatedly asking if they really wanted to go to Charlestown, but he did not say why they should be wary. Once on the bus, the group sensed a tension in the atmosphere they couldn’t quite figure out. Vivian English Washington was a student from Tucson, Arizona: “No one would speak to us on the bus, and we were the only people of color. They were just staring at us, as if to say, ‘Why are you here? What are you doing on this bus?’ ”

At the monument the group enjoyed touring the landmark with cordial park rangers and tour guides. When they were done, they simply headed back down the hill toward the stop at the corner of Lexington and Bunker Hill streets to catch their return bus trip.

However, while waiting for the bus in the afternoon sunlight of a very chilly day, a few of the students noticed something out of the ordinary.

“The kids were very, very observant of this maroon car that had been circling very, very, slowly,” remembers Battles. “They said, ‘Mr. Battles, this car keeps circling the block.’ I wasn’t paying attention, but they were.”

The bus finally arrived. “The same maroon car circled around real quick and double-parked next to the bus,” says Battles. “Some guys jumped out of the car swinging ax handles, golf clubs, baseball bats.” He recalls just standing there stunned for a moment, wondering what was going on. “Our first reaction, of course, was to get the kids on the bus. Other passengers who were not from our group tried to push our students out of the way so they could get on the bus. Our young men gathered the girls and pushed them on the bus. We were, of course, the ones getting hit while we got the girls on that bus. Two panicked and ran down the street, so I went after them.”

John Jones, who had found his way to PFA by way of Chicago and California, was one of the students assaulted. “I was trying to withstand the blows, and I couldn’t withstand them,” he remembers. “I tried to look to the left, to the right, to see what I could do to get out of the situation. The minute I moved my arms, one of them came right to me. I was helpless. I couldn’t get on the bus, and I couldn’t get away from them. I put my hands on my head, and to my surprise, I did not feel any of those licks. I did not feel any pain.”

Jones was sick with a fever that day, so to keep himself comfortable in the chilly weather he had heavily layered his clothes. He believes those extra layers may have actually saved him from worse harm.

The young women already on the bus watched what was happening in absolute horror.

“When I got on the bus, I turned around and looked to the side out of the window, and I saw those guys beating our guys. I saw Mr. Battles, I saw all our guys with their hands up trying not to be hit on their heads, and [the perpetrators], they’re swinging . . . there was a golf club, a hockey stick, an ax handle, a baseball bat, all of them had something. Two of our girls never got on the bus. And the people on the bus just stared at us. We were begging and crying for them to help us and call the police. They looked at us like we were zombies or something from outer space. Nobody, not even the bus driver, helped us,” remembers Washington.

When the blows finally came to an end, five had been brutally assaulted. The four young men—the late Fred Walters, Mark Washington, Samuel Perry, and John Jones, along with Battles, somehow managed to get on the bus. Battles didn’t even realize he’d been hit until his wife pointed out the blood gushing from a head wound. One passenger stepped forward to give him a T-shirt to wipe the blood off his face. The bus then went to where the two young women who had fled had taken shelter, and picked them up. From there the driver was persuaded to take the group to the District 15 police station in Charlestown.

En route to the station, the wounded students were lying in the aisles of the bus in shock and pain. “It was just so shocking because we had done nothing wrong,” says Shirley Sims, a student from Philadelphia. “We were well dressed and just standing on the corner waiting for the bus like any other tourists. There was some bleeding and tears. We were very frightened.”

But the students had already gained the upper hand from the fact that none of them retaliated. The story could have certainly gone another way if they had. Instead, once on the bus, their true integrity and dignity shone brightly when they gathered and prayed. “There was a whole change in atmosphere on the bus,” says Jones. “They weren’t expecting us to kneel down and pray right there on the bus, right there at that scene. And when that happened, it gave us courage, it gave us a little peace and calm, so it was a natural thing that we all came together to start praying.”

Once at the police station, it was apparent the five assaulted individuals needed medical care, so an ambulance transported them to the hospital. “They took us to Massachusetts General Hospital, and the nurses and attendants kept asking if we were ever knocked unconscious,” Battles recalls. “The severity of the blows—they felt we should have been knocked unconscious. Some had been hit on the head, some were hit on their arms, shoulders, and on the back. We said ‘No, no.’ But we just knew that it had been the Lord, that God had protected us from being really hurt.”

The rest of the students remained at the police station with Mrs. Battles to file a report. “When we got off the bus and went into the police station, we immediately drew the attention of everybody there when we started saying what happened,” says Washington. Finally, with all the statements taken, the officers prepared to take the students and Mrs. Battles to the hospital to reunite them with the others.

“When my friend Glenda and I walked outside to get into the police car, there was the [maroon] car parked outside the station!” Washington says. “So we went over and looked in the back of the car, because the windows were down, and there were three of the [weapons] they had used to beat our guys. They were on the bottom floor of the back seat.”

The girls quickly alerted the police, who discovered two of the assailants on the premises in the courthouse next door, taking care of other business. They were soon arrested.

Once they were at the hospital, the outlandish severity of the attacks got the attention of the media. Before long, the place was swarming with reporters and cameramen eager to find out what had happened to this group of 14 from Pine Forge Academy—a place no one there had ever heard of.

“When I came out, I was very calm,” says Battles. “The students were already out there, and they were talking to the news reporters and giving their stories of what had happened. So they interviewed me, and I gave them my story. By 6:00 p.m. we were all over the television.”

Because of the nationwide attention given to the racial tensions in Boston, the story was not just of local interest but made national headlines. Then-mayor Kevin White visited the group at the hospital to offer his personal apologies and conducted a formal press conference to denounce the attackers, calling the incident an “ugly scar on Boston.” That a group of tourists—students on an academic field trip—could be targeted and attacked simply for the color of their skin and being in a part of town where they were unaware they were unwelcome did not look good for the city.

Once released from medical care, the PFA 14 could not immediately return to campus. They needed to remain in Boston a little longer to positively identify their attackers, make further statements, and go before a grand jury to see if the case had enough evidence to go to trial.

At that point the city of Boston stepped in to try to make their stay a little more comfortable. They had spent the previous few nights camped out with members from the Berea church; but now they were given new accommodations in Parker House, one of the most exclusive hotels in Boston at the time. Their transportation was provided by limousines instead of city buses. And the group was treated to meals and entertainment. The kids were met with a standing ovation from state representatives when they toured the Massachusetts State House. “I remember the city really tried to roll out the red carpet for us, and really tried to make us comfortable. They placed us in a very nice hotel and made sure we ate well and were taken care of,” remembers Sims.

During the course of the following week, the group spent their days giving testimony. “We would go down to the district attorney’s office, we would go to the grand jury for preliminary hearings, and each of the students were taken in to give their account,” says Battles. “Of course, the account of each of the students was basically the same. Then the police came to the hotel on several occasions with pictures of guys who had been in trouble with the law to see whether or not [the students] could pick them out. Half of the students were able to positively identify three of those guys as ones who were in the car.” During that week the group was joined by Carol Cantu, a PFA faculty member and PR representative, and Principal Auldwin Humphrey, to guide and give support in the wake of thetraumatic incident. They visited historic Plymouth on Sabbath, and by Sunday flew back to Philadelphia to return to Pine Forge Academy, tickets courtesy of the city of Boston.

Back on campus, the group tried their best to get back into regular life. But after going through such a horrific event, it wasn’t easy. “I think you work hard to get back into your regular routine because it’s comfortable, and we all did that. As shaken as we were, we all did that,” says Sims. “I think we all became just a little closer to each other, certainly after the trip.”

“What surfaced out of all of this was how could high school students react in such a mature and Christ-like attitude under such adversity.”

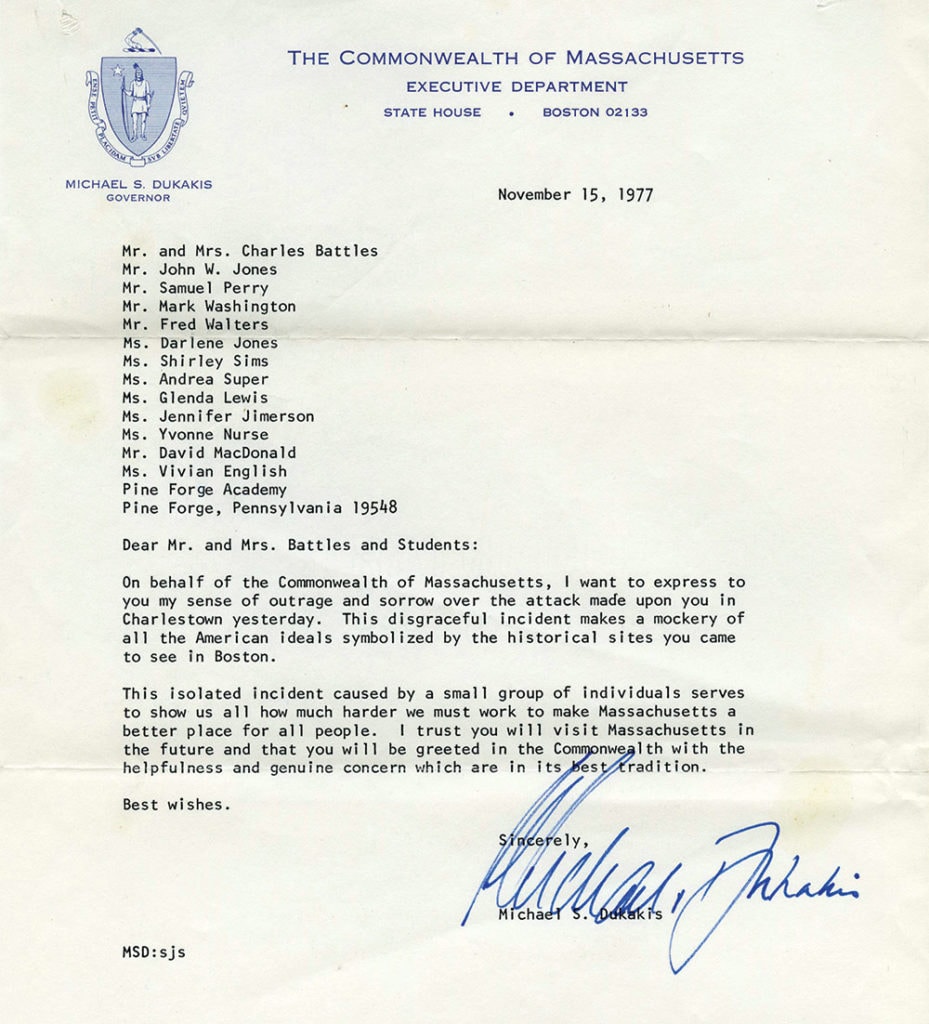

Phone calls and letters poured in to Battles and the students before the case went to trial. Then-governor and eventual presidential candidate Michael Dukakis wrote a letter. Well-wishes were also received from Massachusetts’ U.S. senators Edward Brooke and Edward (Ted) Kennedy. Everyday folk—all strangers—reached out as well, sending letters expressing their deep sorrow for the incident, their sincere apologies as Bostonians, and their admiration for the dignified manner in which the students and their chaperones handled themselves. Suddenly Pine Forge Academy and its Adventist Christian philosophy of educating and mentoring young people became known around the nation.

“What surfaced out of all of this was how high school students could react in such a mature and Christlike attitude under such adversity,” remembers Battles. “Throughout the grand jury testimony people said, ‘Tell us about Pine Forge Academy. Tell us about your church.’ And so the students were able to witness about what we believe as Adventists as well as what Pine Forge stands for. [They] definitely represented Adventism and Pine Forge Academy in a positive light.”

Three young men—Vincent Tamburello, Jr.; Daniel Krystyn; and Kenneth Laudenslager—all residents of Charlestown, went to trial in late 1978 after a year of investigation. They were charged with 42 counts of assault in connection with the attack on the Pine Forge Academy 14.

By then the seniors in the group had graduated and gone to college—several to Oakwood University in Alabama. The city of Boston once again picked up the tab to fly them all in and put them up in Parker House. But even with the positive identification of the suspects by several students, which included identifying the car and the weapons used in the attack, the three men were acquitted by an all-White jury.

“I cried,” recalls Vivian English Washington. “I cried because I saw the injustice. Nine of us, nine, positively identified those guys. And they were acquitted. I was just so disappointed and hurt. Where was the justice? We were beaten. We didn’t bother anybody. All we wanted was to view a piece of history.”

In November 2017 several members of the original Pine Forge Academy 14 group traveled to Boston on the fortieth anniversary of the attack. The reunion provided time to reflect on what happened then, as well as to reconnect over an event that impacted their lives forever. During the past 40 years some have written off Boston altogether, while others have let the experience fuel their passion for doing good in the world and advocating for justice for all people.

The incident has touched each person in different ways for sure, with the reality of the acquittal still painful after all these years. But the spirit and grace of those teenagers then, grown and productive adults now, hasn’t been extinguished. “They were acquitted. It was an all-White jury, and they were just acquitted,” says Jones. “It just sent a reality that evil and injustice may seem like it’s going to prevail, but ultimately, you can’t let the opinion and decision and the incident [itself] be a source of distraction and destruction of what you can be, and what you can do to help people and contribute.”

* “History Rolled In on a Yellow School Bus,” Boston Globe, Sept. 7, 2014.

Wilona Karimabadi is an assistant editor of Adventist Review.