I was probably 7 or 8 years old the night Dad called home from a meeting and said he didn’t think he would make it in time to milk Elma, our cow. It turned out to be a life-defining night for the rest of my childhood and youth.

My brother and I had helped Dad for a year or two with the milking, but it was never for long. We would milk a few squirts, then go play in the hay or chase the cats or stick our hands way down deep in the grain bin and inhale the wonderful smell of grain. But this night Mom took my brother and me out to the barn, and we sat down and started: squirt, squirt, squirt, squirt.

For a few minutes things went fine, and we felt pretty good. Mom had tried first and failed. We were doing something Mommy couldn’t. But then our hands started to hurt, and we wanted to quit: just try making a fist and opening your hand; then repeat the action, maybe 500 times, and you will know how we felt.

I can still remember that long evening: taking turns milking, then sitting in the door of the barn crying and holding our aching hands. Dad came in after we were through and said he was proud of us. So proud that from then on, milking, morning and night, was part of our daily chores till we moved from that farm.

Going off to college ensured I’d never be milking again. Or so I thought, until the business manager called me into his office to give me my work assignment: “Homer, I am going to send you to the farm to be one of the morning milkers.”

Every morning I was up at 3:30, over to the barn at 4:00, begrudging the hard, dirty, dairy work, milking the 50 to 100 cows that we milked each day. Sure, there were milking machines; but it was still a lot of smelly work with ungrateful cows. Sometimes one of them would slap my face with her wet, soggy tail or kick me into the gutter. By graduation I was [something of] a cow authority.

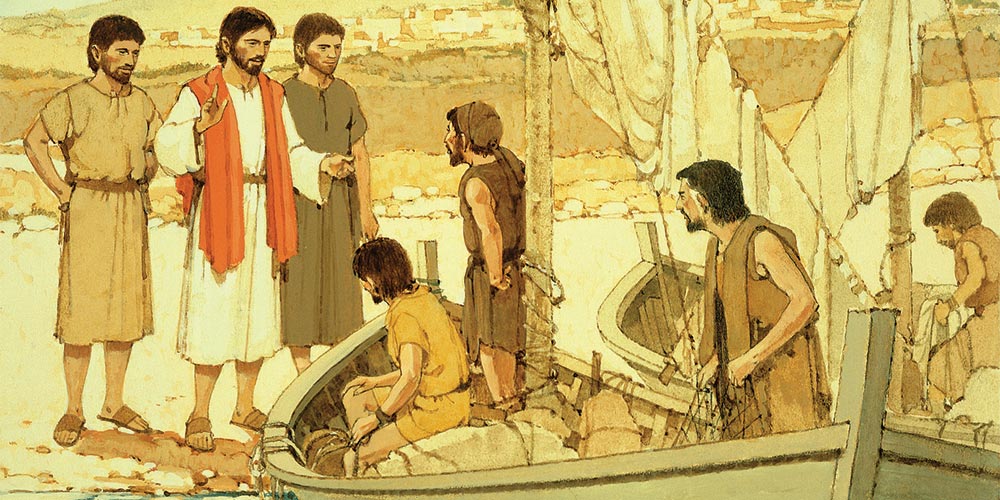

I knew about milking cows, and Peter knew about catching fish. Which is why it must have been awkward for him that morning by Lake Gennesaret, when Jesus instructed him, and whoever else was involved, to “put out into deep water, and let down the nets for a catch” (Luke 5:4).

Peter and his colleagues were already exhausted. They had fished all night and caught nothing; they had pulled their nets out onto the shore and were cleaning them; the long night of work had them feeling down that morning.

Besides, Jesus’ recent behavior had puzzled, perplexed, and maybe even frustrated them. Luke 4:38-44 shows that the work was just getting started in Capernaum: lots of new interests; many people right there to work with. Why would Jesus leave now? It didn’t make sense.

Sometimes launching out can look quite pointless, certainly very unpromising. In the Middle East, Adventist members are located mostly in a few communities—one little strip of Cairo; two or three little groups in Istanbul; Sabtieh in Lebanon; a few groups in the Gulf countries, etc. And even in those localities Adventism is such a tiny minority with so much work to do that we struggle at the thought of branching out into new areas.

I knew about milking cows, and Peter knew about catching fish.

In Jamaica, where there is one Adventist for every nine people, 89 percent of the people have still not accepted God’s final message. There is so much to do right where we live. Why leave and go to some place new?

Jesus, and later Paul, focused much attention on unentered areas and people groups. I certainly am not saying to ignore where we are already working, or to start something, drop it, and move on to something else. That kind of work can do its own share of harm.

But it does help to remember that while we keep going with what has already been started, we must keep looking for places and ways to launch out again. Current success or previous failure need not be proof against branching out into new areas.

Grudgingly, perhaps, the disciples have followed Jesus out of Capernaum. Still having their boats allows that they may have sailed to their new location. Jesus, in character, probably spent the night praying. The disciples, in keeping with their trade, spent their night fishing.

The next morning people started to gather, and Jesus began to preach while the disciples sat nearby working on their nets. Disgruntlement notwithstanding, their hearts still burned within them as they heard Jesus’ words. More and more people kept arriving, until it became almost impossible for Jesus to be seen or heard by all. So He stepped into Peter’s boat and asked him to push out from shore a little bit. From that pulpit He preached the rest of His sermon.

Whatever He said was powerful. Peter may have absorbed it all while standing in the water holding the boat so it wouldn’t drift away; or while sitting in the boat holding a pole wedged between some rocks on the shallow bottom. Whatever he was doing, his mind was on Jesus and His powerful words.

Then he realized that Jesus was done preaching and was talking to him. “Peter,” the Master said softly, “let’s push out to where it is deep and do some fishing.”

It was the kind of remark that unknowing farmers or shopkeepers could make—tourists down by the seaside for a holiday; intrigued by Peter and his companions, so quaint out in their little boats; capturing all the memories in their cameras, and wanting to feel the nets and see the fish; even wanting a ride and asking Peter to “just push out a little ways and show our boys how you fish.”

Ignorant tourists. It was like trying to tell me how to milk cows. If you wanted to catch fish on Galilee, you didn’t sleep in, then saunter down to your boat after a late and leisurely breakfast. You had to be there at evening; you’d fish through the night. Then you could sleep a little during the day.

But then, what do tourists know about fishing? Even carpenter tourists who were good at preaching?

Now the tourists who heard the preacher’s words want to see what Peter does next. And Peter himself doesn’t know. Does he embarrass this wonderful Leader with an informed explanation? The nontourists knew people don’t fish during the day. If Peter does push out, he could become the laughingstock of the whole local community.

Peter tries hard to be tactful, very un-Peter. He doesn’t tell Jesus He is ignorant. He just says that he and his friends have already tried all night; they’re tired now; it’s time to quit and . . . . The look in Jesus’ eyes stops him.

“OK, Lord. Because You have asked me to, I will do it.”

The miracle most celebrated in this story is the netful of fish. But there is another: the one that took place just before Peter obediently pushed out his boat; the miracle that made Peter say, in effect, “Lord, what You suggest makes no sense at all to me. You are a carpenter-preacher from Nazareth. I am the Galilean fisherman. But because You say to, I will launch out into the deep.”

This was the miracle of a heart so affected by Jesus that Peter was willing to let go of everything that made sense to him—all the built-up traditions of ancestors, all the established practices of his own ample experience—and do what might make him the laughingstock of his Galilean world.

Peter’s “deep” will not be everyone’s deep. But his miracle is replicated a thousand times as men and women agree to serve because they choose to follow God’s voice (see Rom. 8:14): maybe in an overseas assignment; or perhaps, in apartments downtown. Or else, making a financial sacrifice as you have done before; or attempting a share-your-faith venture yet again where you feel you have failed before.

Letting down your net may mean investing your next six years in a needy community, taking years to get to know its people so you might find appropriate ways to reach their hearts. Launching out may get you lockups, stonings, cat-o’-nine-tails, shipwrecks, and journeys in a basket flung over a wall (2 Cor. 11:23-33). For Waldensian youth, launching out meant infiltrating the heart of the enemy’s territory with the Word of God, knowing full well that many of them would never return home.

Early Adventist missionaries traveled by donkey cart for months into areas where there was no possibility of medical care. They were pushing out into the deep, whether the deep of the South American jungle or the perilous shallows and rapids of the Amazon. And many of those who launched out at God’s command have fallen and been buried in the lands of their sacrifice.

In the 1800s Lilias Trotter, a wealthy young woman and gifted artist, fell in love with Jesus, dedicated her life to Him, and launched out into the deep. Leading art critics were hailing her as probably destined to become the best British artist of the nineteenth century. But leaving wealth, power, and prestige behind, Trotter moved to North Africa to spend the next 40 years sharing the gospel with the people of Algeria. She learned Arabic, started schools, wrote books and tracts, helped with Bible translation, and took long journeys into the desert by camel train to visit scattered communities. She served until her death, and they buried her in Algiers.

On the shores of Galilee, Peter surrendered his expertise and launched out into the deep because Jesus said so. In England, Trotter set aside a brilliant-looking future and went to North Africa because Jesus said, “Go.”

The miracle God means to do in and through us needs neither our judgment nor our competence. It just needs the prior miracle of obedient conformity to Him that mirrors Peter saying, “Lord, I’ll go because You say so.”

Homer Trecartin is director of Global Mission Centers and Total Employment at the General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists, Silver Spring, Maryland, United States.