On September 5, 2014—in the presence of ministries-of-health leaders, ambassadors, administrators, and health professionals—the World Health Organization (WHO) in Geneva issued its first-ever comprehensive report on suicide.1 Its goal was to reduce the rate of suicide by 10 percent by 2020. The presenters’ research and statistics showed that suicide occurs in all regions of the world, and throughout peoples’ life spans. Among young people ages 15-29, suicide is the second-leading cause of death. Yet suicides are preventable through a multisectorial strategy. Such strategy must involve policymakers, health workers, and communities, including our own Seventh-day Adventist churches, hospitals, and clinics.

Suicides take a high toll. More than 800,000 individuals die from suicide every year, one every 40 seconds. For each adult who dies from suicide there may be more than 20 others who have attempted to do so. Since it’s a sensitive issue and even illegal in some countries, it’s probably underreported.

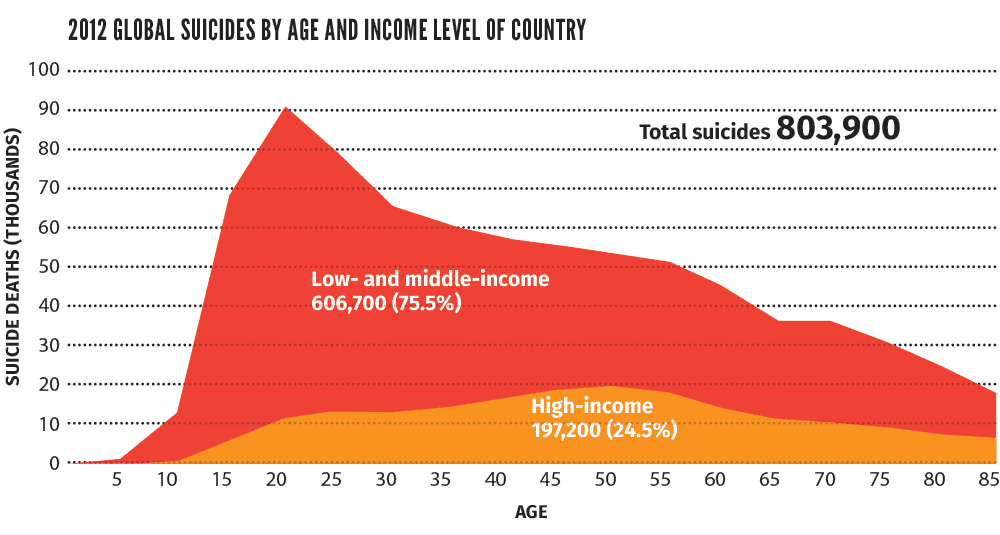

Seventy-five percent of suicide deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries, the highest number among young people between 15 and 29 years of age.

Proportionally, however, in most regions of the world, suicide rates are higher in those aged 70 years or older, for both men and women.

Three times as many men die by suicide as do women in the richest countries (3.5 male-to-female ratio). In the low- and middle-income countries, the male-to-female ratio is lower (1.6 male-to-female ratio).

The good news is that between 2000 and 2012 the number of suicides fell by 9 percent, from 883,000 to 804,000. One possible explanation is the dramatic improvement in global health in some countries throughout the past decade. This reduction confirms that improvement is possible. In some regions, however, the suicide rate has increased. In Africa, for example, it has grown by 38 percent.

Mental health declines

Risk factors:

Job and financial loss

Chronic pain

Harmful use of alcohol

Mental disorder

Previous suicide attempt

Relationship conflict

Isolation, lack of social support

Trauma or abuse

Access to means

Stigma and taboo

Inappropriate media reporting

Mental health improves

Protective factors:

Strong personal relationships

Resilience against stress and trauma

Sense of self-worth

Religious or spiritual beliefs

Supportive community

Self-identity

Effective problem-solving skills

Healthful lifestyle choices

Regular exercise

Adequate sleep and diet

Support for those seeking treatment

Being confronted with someone with suicidal ideas is frightening and uncomfortable. It’s generally thought that talking about suicide is a bad idea and can be interpreted as encouragement. Unfortunately, this myth isolates despondent ones in their suffering and quest for relief. In 25 countries suicide is a crime, and survivors might be sent not to a hospital, but to jail.

It is well recognized, however, that one of the best ways to prevent suicide is to offer an open space for communication. Mental health professionals often ask the question to distraught or desperate patients: Do you think about death or dying? If the answer is yes, they will continue by asking: Do you think about killing yourself? What has helped you to stay alive up to now? Could you make a commitment to call for help in case of pressing suicidal ideation?

Through presence and dialogue, individuals may be led to take some distance from pain and hurt and to weigh the consequences of such a radical choice. This approach has saved many lives.2

As outlined in the figure below, research indicates that there are many risk and protective factors for suicide. The presence of protective factors increases mental health and decreases the risk for suicide.

Restricting access to the means for suicide works. An effective strategy for preventing suicides and suicide attempts is to restrict access to the most common means, including pesticides, firearms, and certain medications.

Primary health-care services need to assess the risk during routine visits, incorporating suicide prevention as a core component of routine health care. Mental disorders and harmful use of alcohol contribute to many suicides worldwide. Early identification and effective management are key to ensuring that people receive the care they need.

Communities play a critical role in suicide prevention. They can provide social support to vulnerable individuals and engage in follow-up care, fight stigma, and support those bereaved by suicide. In India the monthly visits of nonprofessional community health workers to individuals who have attempted suicide have decreased the rates of completed suicide in significant numbers. Imagine if our churches were to do that!

The stigma of suicide could be reduced with more awareness in society and particularly in the church, which would allow people to seek help more readily. We need to talk about suicide, and people need to see the church as a safe haven. If people feel hopeless, they can come to us to find hope in Jesus Christ and renewed purpose. That’s what we as a church are all about.

Members and leaders can support the effort by participating in individual and corporate action. Adventist hospitals and clinics should embrace the call to early recognition of emotional distress in primary-care settings and offer a continuum of specialized care, including mental health services where faith matters are included as active components of the restoration. Adventist universities that train ministers, health workers, and mental health professionals should actively teach principles to recognize and treat those suffering from emotional pain, as well as their families, drawing from the teachings of Scripture, the Spirit of Prophecy, and sound science.

Individuals can contribute by recognizing depression risk factors and identifying individuals at risk. They can also set an example by living a balanced lifestyle and urging people to refrain from consuming recreational substances, including alcohol, in order to maintain mental health and emotional well-being.

Finally, a caring church community can see suicidal thoughts not as a lack of faith but as a time of spiritual distress (see text box) and a cry for support and compassion. A survivor from a suicidal crisis has said, “The compassionate presence of a friend has been as worthy as 10 years of psychiatric care.”

When we do that, we are extending the healing ministry of Jesus.

This ministry of love and compassion needs to be extended to those left behind in a lonely, deep, and dark pit of pain, grieving loved ones taken by suicide. Despite the best efforts of family members, friends, and health providers, suicide happens. An anonymous letter from someone who had been very close to committing suicide provides perspective: “I had a loving family, a very good and supportive doctor, but when you reach this tunnel, it seems that nothing matters.”

One of our seasoned clinicians experienced the loss of a patient through suicide. Although it happened more than 10 years ago, it’s remembered as if it happened yesterday.

It was a Thursday during the noon hour. The patient had been in treatment for more than three years with chronic suicidal ideas, multiple attempts, and several admissions to the psychiatric hospital. The immediate impact was extremely painful. Just a simple walk along a lake became difficult for the clinician, as the last shop on its shore was named The Last Stop. It seemed as if almost anything could bring back memories of this patient’s death. The family invited the clinician to the funeral service and asked him to be a pallbearer. With every step the clinician was thinking,

Here I take you to your final rest. The gratitude of the family for the clinical work he provided was his source of consolation. “You gave her—and us—three more years,” they said.

| Myths | Facts |

|---|---|

| Talking about suicide is a bad idea and can be interpreted as encouragement. | Talking openly can give an individual other options or the time to rethink their decision, thereby preventing suicide. |

| People who talk about suicide do not intend to do it. | A significant number of people contemplating suicide share their experience of anxiety, depression, and hopelessness and may feel that there is no other option. |

| Most suicides happen suddenly, without warning. | Most suicides are preceded by warning signs, whether verbal or behavioral. Some suicides occur without warning. |

| Someone who is suicidal is determined to die. | Suicidal people are often ambivalent about living or dying. Access to emotional support at the right time can prevent suicide. |

| Once someone is suicidal, that person will always remain suicidal. | Heightened suicide risk is often short-term and situation-specific. |

| Only people with mental disorders are suicidal. | Suicidal behavior indicates deep unhappiness but not necessarily mental disorder. |

But the pain felt by the treating clinician did not compare to the pain felt by the family. Within a year the patient’s elderly parents passed away deep in grief. The mother had declined treatment and accepted only palliative care. Both sisters were overpowered by grief and depression and were unable to work for years following the event. One of the sisters struggled with a wrenching sense of guilt, resulting in her feeling suicidal for several years. Everyone involved suffered. Their faith was one of the only elements that brought them solace. Years of treatment eventually restored the surviving sisters to their work and their families.

However difficult recovery may be, there is hope. The role of friends, pastors, counselors, and the survivor’s faith cannot be underestimated. The surviving mother of an adult child that committed suicide renewed her faith in the Lord’s grace to accept what came her way. She found refuge in the consistent love and care of her daughters and sought help from a psychotherapist to deal with elements of guilt and find the emotional capacity to forgive those she felt had contributed to her child’s desperate end. Wherever there is grace, there is hope.

As a church, we may not have been as consistent in responding to emotional pain as we have been in other areas of health and lifestyle. Perhaps we have not read the Bible as clearly as we should have. Consider the words of the prophet in Isaiah 61:1-3. The language used is suffused with an invitation to care for those in emotional distress:

“The Spirit of the Sovereign Lord is on me, because the Lord has anointed me to proclaim good news to the poor. He has sent me to bind up the brokenhearted, to proclaim freedom for the captives and release from darkness for the prisoners, to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor and the day of vengeance of our God, to comfort all who mourn, and provide for those who grieve in Zion—to bestow on them a crown of beauty instead of ashes, the oil of joy instead of mourning, and a garment of praise instead of a spirit of despair. They will be called oaks of righteousness, a planting of the Lord for the display of his splendor.”

Ellen White described how Jesus ministered. Again, notice the words that denote the Savior’s attentiveness to the emotional needs of those who came in contact with Him:

“It was [Jesus’] mission to bring to men complete restoration; He came to give them health and peace and perfection of character.”

3 “During His ministry, Jesus devoted more time to healing the sick than to preaching.”4 “The Savior made each work of healing an occasion for implanting divine principles in the mind and soul. This was the purpose of His work. He imparted earthly blessings, that He might incline the hearts of men to receive the gospel of His grace.”5 “Gracious, tenderhearted, pitiful, He went about lifting up the bowed-down and comforting the sorrowful. Wherever He went, He carried blessing.”6 “Christ recognized no distinction of nationality or rank or creed.”7 “He passed by no human being as worthless, but sought to apply the healing remedy to every soul.”8

May we as followers of God manifest the Spirit of Christ and “in humility value others above yourselves, not looking to your own interests but each of you to the interests of the others. In your relationships with one another, have the same mindset as Christ Jesus” (Phil. 2:3-5).

Bernard Davy, M.D., M.P.H.,is head physician for Psychiatry Service, Clinique La Ligniere, in Gland, Switzerland. Carlos Fayard, Ph.D., is associate professor of the Department of Psychiatry, Loma Linda University School of Medicine, and assistant director for Mental Health Affairs, Health Ministries Department. Peter Landless, M.D., is director of Adventist Health Ministries, General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists.