An article in the early nineteenth century decried the invention of the stovepipe. The author predicted that this new contraption would almost certainly bring about the dissolution of the family. Simply put, the fact that families huddled together around the family hearth (or candles) in the evening was being eroded simply because tight-knit families could now spread out through any number of heated rooms in the home. Such new, modern technology was initially considered a threat, although this first major domestic appliance was quickly adopted throughout America. After all, it saved time and energy. Doomsayers had to look elsewhere to find reasons for the breakup of American families.1

In today’s world it’s easy to pine after an earlier, simpler time. One must, at times, wonder if some of today’s problems could simply be alleviated, or even eliminated, by simply going back to a more pristine time. Such notions are evident within mainstream culture with television shows that feature a return to the wilderness, the many books by Laura Ingalls Wilder, or the promises of politicians. So what would it be like to go back in time? Let’s imagine living in the days of the early Adventist pioneers.2

Dirt was the most obvious feature of daily life in antebellum America.3 The potent mix of constant fires, trash, and refuse could rankle the nose. Americans tended to put up white picket fences around their houses—not to keep pets inside their yard, but rather to keep street animals out! It was just difficult to stay clean. Since local modes of transportation required mostly the use of horses, this meant that roads were very dirty places. Any significant rain could mix mud with manure to create soggy filth, resulting, at times, in roads that were downright impassable.

America was largely composed of rural farms. A step back in time would undoubtedly reveal that most daily conversations revolved around the rhythms of agriculture. Since books were expensive, most people owned only (in addition to the Bible) a copy of the Farmer’s Almanac—the best-selling book in pre-Civil War America.4

Agriculture dominated daily life in many other profound ways. Even the planning of weddings was timed to coincide with agricultural rhythms (most often conducted in the farmhouse of the bride’s family—it was not until the later Victorian period that people adopted the fashion of wearing a white wedding dress with a minister officiating at a church). People tied the knot in the early spring or late fall, because of planting or harvesting. The preferred nuptial time was around Thanksgiving.

Historians have noted a significant spike in the birth of children in late winter or early spring that corresponds with the early stages of planting—the time when most adults had the least amount of work on the farm.5 Children typically received an education during the coldest weeks of winter in “reading, writing, and arithmetic.”6 Most children had only a few years of education before their labor on the farm outweighed their “school learning.”

If farm life was difficult, American health care was positively dangerous. In perhaps the most striking divide between past and present, illness “was a matter of virtually certain occurrence but uncertain outcome.”7 Virulent diseases swept across America with very few cures available. Malaria, yellow fever, and the dreaded consumption (tuberculosis) ravaged homes. Most parents expected that at least one or more children would not survive to adulthood (the child mortality rate was 10 times what it is today).8 Adults fared not much better, with the danger of accidents, and, for women, the high mortality rate associated with giving birth.

“Most people did not survive much past the beginning of today’s retirement age.”9 Many marriages were torn asunder, not by divorce, but by premature death. In a time of heroic medicine, as people looked to restore balance to the body, most treatments were downright dangerous. It is no wonder that the life span of people during this time would remain constant until the adoption of public health and antiseptic measures still decades in the future. Adventist historian George Knight remarked that no person in their right mind would choose to be born in the nineteenth century!10

Despite such travails, what if one could belong to an earlier and somehow purer version of Seventh-day Adventism—a time during which the early pioneers thrived and held the leadership of the movement?

Unfortunately, most people today would scarcely recognize the world of the early pioneers. Ellen White was rather hesitant when she first heard about Joseph Bates and the seventh-day Sabbath. She thought he “erred in dwelling upon the fourth commandment more than upon the other nine.”11 After intense Bible study she adopted the same position.

Similarly, the diet of most early pioneers consisted of lots of grease, spice, and meat. Even the position on clean versus unclean meats did not really develop until the 1890s. Not until this latter period did Ellen White finally adopt a completely vegetarian diet. Many people today might feel rather uncomfortable if they could go back in time to share a meal with these early believers.12

Conversely, many early pioneers would similarly be uncomfortable with today’s current Statement of Fundamental Beliefs. Some, such as Uriah Smith, had trouble with belief 5, about the personhood of the Holy Spirit. In the first portion of his long career, Smith not only denied the Trinity and the eternity of the Son (like many of his fellow believers), but he pictured the Holy Spirit as “that divine, mysterious emanation through which they [the Father and the Son] carry forward their great and infinite work.” On another occasion Smith pictured the Holy Spirit as a “divine influence” and not a “person like the Father and the Son.”13

This wasn’t the only position with which pioneers would sense discomfort. Early on, the pioneers struggled with the “shut door” theory that probation closed after October 1844. Ellen White initially shared this perspective, but later repudiated it. Even the time for when to begin the Sabbath was open to debate. Some (like the seafaring Joseph Bates) advocated for a set time (6:00 p.m.), but it was only after a detailed Bible exposition by J. N. Andrews that the church eventually adopted the position of sunset to sunset as the only biblically defensible position.14

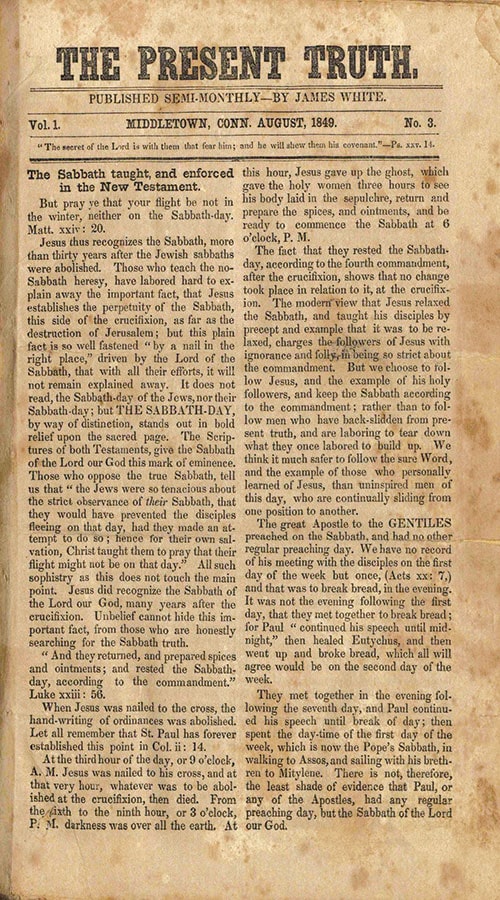

From the very beginning, the pioneers who eventually formed the Seventh-day Adventist Church adhered to the conviction that truth is progressive. The very name of the Sabbatarian Adventist periodical, the precursor to the Adventist Review, was titled The Present Truth. Adventists upheld a dynamic concept and commitment to biblical truth as expressed in the Bible. It was such a spirit that caused J. N. Andrews, after his discovery of the Sabbath truth, to exclaim that he would gladly “exchange a thousand errors for one truth.”15 This does not mean that pillar doctrines established through Bible study would erode away, but instead it was through careful Bible study that the denomination would continue to grow in its understanding of truth. In fact, God’s truth as manifested in the person of Jesus Christ and revealed in His Word will be a topic that God’s people will study throughout all eternity!

A favorite book of mine is titled simply The Good Old Days: They Were Terrible! Life was tough in nineteenth-century America. The early Sabbathkeeping Adventists who eventually formed the Seventh-day Adventist Church faced incredible challenges, both in terms of the development of their theology as well as lifestyle. No person aware of all of these challenges would willingly go back!16

George Knight points out that all societies suffer from, what he calls, “historical myopia.”17 People romanticize the past, whether it is certain people, events, or places from “long ago” and “far away.” They dream about the “good old days” when life was simple and unspoiled. Unfortunately, such a time never existed. In fact, such a mythology distorts truth.

So why do people suffer from “historical myopia”? The answer is simple. The human mind plays “tricks” on us “through the psychological process of repression. Repression allows our minds to forget the unhappy events of the past while remembering much of the good.”18 Such a view of the past is particularly destructive because it does not deal with the stark realities of the past and present, or the challenges of today or tomorrow. It has a tendency to create a view of the world, the church, or even lives that everything is “going to pot” despite our best efforts.19

What is the greatest danger that Adventism faces today? Ellen White admonished, in the wake of the Minneapolis saga of 1888, that it is “if we are not constantly guarded, of considering our ideas, because long cherished, to be Bible doctrines and on every point infallible, and measuring everyone by the rule of our interpretation of Bible truth. This is our danger, and this would be the greatest evil that could ever come to us as a people.”20

A careful study of the past reveals the need for a candid appraisal of both the challenges as well as an admiration for the Adventist commitment to “present truth.”

Michael W. Campbell, Ph.D., serves as an associate professor of Adventist Studies at the Adventist International Institute of Advanced Studies in Silang, Cavite, Philippines.