The howls of wolves were unmistakable. The moon was full, and the pack was on the prowl. Inside a sparsely furnished cabin a small group of researchers huddled anxiously in a corner. Strangely, they weren’t at all concerned about the hunt outside. Instead, their attention was focused on a computer screen displaying results from years of painstaking research. The story told by the graphs and statistics was as riveting as the howls that pierced the night air.

These researchers were studying the Yellowstone National Park ecosystem in the United States, where wolves were reintroduced in 1995 after being killed off nearly 70 years prior. Remarkably, the findings suggested that the presence or absence of just one species—the wolf—could potentially affect an entire ecosystem.1

Shortly after the wolf was restored, the elk that the wolves hunted changed their behavior and moved away from their favorite grazing areas. The aspen forests and streamside vegetation began to grow again when the saplings were no longer consumed by the elk. Next, amphibians, reptiles, beavers, and songbirds staged impressive comebacks as vegetation increased. Tree roots stabilized the stream banks and reduced erosion. Beaver activities raised the water table. Thus, the wolf’s presence in Yellowstone appeared not only to improve the ecology and richness of the ecosystem dramatically, but indirectly changed its physical geography as well!

So what have we learned from Yellowstone’s wolves? Complex relationships exist among plants, animals, and their abiotic environment. By altering just one component, we often change that environment in unforeseen ways. The lesson is clear: we should reflect carefully on how we treat creation.

The wolf is a fitting icon of humankind’s relationship to nature. Our need to subjugate nature and tame it to our liking is typified by the expression “the only good wolf is a dead wolf.” Early Americans declared war on the wolf, and sought to exterminate it with bounties that resulted in the deaths of millions of wolves.

Today the tables have turned dramatically. As Americans have become more environmentally conscious, wolf preservation has become a rallying cry. Nevertheless, some continue to deplore the policies that maintain the wolf’s existence in Yellowstone. Through no fault of its own, the once-feared shaggy canine has found itself at the center of a controversy between those who support and those who oppose hands-on creation care.

We live on a rapidly deteriorating planet. The profound impact of humanity has been devastating and undeniable.2 Almost a quarter of the earth’s land area has been converted for human use. Nearly half of our tropical and temperate forests have been chopped down or bulldozed. Pollution of our air, land, and water has become pervasive. Because of our overexploitation and neglect, plants and animals are disappearing at unprecedented rates, with thousands of species becoming extinct each year. By transporting microbes, plants, and animals to new places, we have unwittingly spread diseases and greatly accelerated extinctions of native species.

Does the Creator who declared all life-forms “very good” (Gen. 1:31), who lovingly feeds and waters the creatures (Ps. 104:24-27; Isa. 43:20; Matt. 6:26), and who sees the sparrows that fall (Matt. 10:29), take notice of what has become of His creation? Does He see that “the whole creation groans” (Rom. 8:22, NKJV)?3 Of course He does.

Some Christians express more concern about the current state of God’s creation than others. Many read in Scripture a clear mandate for us to care for creation, yet others see implicit permission to plunder it. Curiously, numerous published surveys reveal that Christians and those of other faith groups are measurably less concerned about environmental issues than the public at large.4 Why should this be?

At least three reasons explain the indifference or even anti-environmental sentiments of some Christians.

First, some argue from dominion theology (Gen. 1:26, 28) that God permits humans to exploit natural resources without concern for consequences.

Second, our eschatological views lead some to insist we need not be concerned about our earthly home and its creatures because this world will be destroyed and re-created at the second coming of Jesus.

Third, the aforementioned studies show that environmental attitudes can be strongly influenced by political leanings and media exposure.5

Many Christians take offense at the secular view that the creation came about by natural processes over millions or billions of years. Yet some of these same Christians express anger toward those who believe we should care about that which remains of creation. They denounce government efforts to curb environmental damage. They believe that many environmental concerns are grossly distorted, and serve surreptitious purposes. They insist that pro-environmental scientists and politicians—and those Christians who agree with them—are crying wolf.

So how should Seventh-day Adventists and other Christians relate to the creation? Here are four reasons I believe we should embrace environmental stewardship.

Scripture makes a compelling case for environmental stewardship. Properly understood, the “dominion” given humans to “rule” over all living things and “subdue” the Earth (Gen. 1:26, 28) refers to His expectations for us to take care of the land (Ex. 23:10, 11; Lev. 25:2-7, 23, 24) and to treat animals humanely by providing them sufficient food and rest (Ex. 23:5, 12; Deut. 25:4), rescuing them from harm (Matt. 12:11), and never torturing them (Num. 22:23-33). The world and everything in it belongs to God, not us (Lev. 25:23; Ps. 24:1; 1 Cor. 6:15-20, 10:26). God even authorized the first “environmental protection act” (Gen. 2:15) and the first “endangered species act” (Gen. 6:19).

Clearly, God expects His appointed rulers of creation to exercise benevolent, selfless stewardship (Ps. 72:8-14; Eze. 34:2-4; Matt. 20:26, 27).

Christians who seek to preserve creation recognize the clear relationship between our understandings of nature and God: “But ask the animals, and they will teach you, or the birds in the sky, and they will tell you; or speak to the earth, and it will teach you, or let the fish in the sea inform you” (Job 12:7, 8).

Ellen White urged upon us the importance of studying and preserving God’s creation. “God has surrounded us with nature’s beautiful scenery to attract and interest the mind. It is His design that we should associate the glories of nature with His character. If we faithfully study the book of nature, we shall find it a fruitful source for contemplating the infinite love and power of God.”6

Indeed, let’s study nature, learn from it, and preserve it for future generations to do the same!

God has bequeathed to us extraordinary natural resources that make our lives comfortable and productive. But these resources are finite and subject to overexploitation.

We can characterize natural resources as ecosystem services, which we depend upon for our very existence. They include provision of food and water; pollination of native and agricultural plants; cycling of nutrients; moderation of extreme weather, including flood and drought mitigation; protection against erosion; regulation of plant pest and human disease organisms; decomposition and detoxification of wastes; purification of air and water; and maintenance of biodiversity. These services, provided to us for free, have been valued globally at $125 trillion per year.7 Obviously, they’re irreplaceable.

Without these services, which we are rapidly degrading, our quality of life—and that of future generations—would be fundamentally diminished.

Healthy humans need healthy environments that provide natural resources and processes that sustain human life. Unhealthy environments provide diminished ecosystem services and promote disease, tension, conflict, and inequality. Sadly, those who are poor and impoverished usually bear the brunt of problems that arise from unhealthy environments. Selfish individuals and corporations often conduct business in ways that exploit the environment and diminish its capacity to sustain local people. Wealthy nations often benefit at the expense of developing nations.

Lax environmental regulations or corrupt disregard of them threaten the health and livelihoods of millions. An estimated one in seven human deaths in 2012 resulted from exposure to soil, water, and/or air pollution, and 93 percent of these 9 million preventable deaths were in developing countries.8 As Christians, we should have the loudest voices in defending the victims of environmental injustice, which include not just humans but also other life forms.

As followers of Jesus, we have an obligation to care for creation and to alleviate human suffering whenever we can. Yet understanding how we should do so is made more difficult by the polarized opinions we hear. When it comes to environmental issues, we should seek to become informed by the most reliable sources. We should recognize the language of propaganda that we encounter daily in the media and blogosphere, often from pundits who understand little about complicated interactions of the natural world. We need to be open-minded to the possibility of holding wrong views, apply critical thinking to the best of our abilities, and treat with respect the views that others hold, even if we believe they are wrong.

As it turns out, further study has questioned the primary role of wolves in restoring Yellowstone’s ecosystem. Although the wolves certainly contribute by preying on the elk, the picture appears to be more complicated than originally believed, as it also involves interactions among bison, beavers, human hunting, rainfall patterns, and temperature changes.9 As a human enterprise, science has its imperfections, but when used correctly to test alternative hypotheses, it is eventually self-correcting. Science provides a way of gaining knowledge and insight about the creation; it is God’s gift to help us gain understanding.

The indifference of many Christians toward environmental issues prompted renowned Harvard biologist E. O. Wilson to publish in 2006 his insightful book The Creation: An Appeal to Save Life on Earth. Couched in the form of a series of letters to a fictitious Baptist minister, Wilson pleaded for Christians to join the largely secular effort to save what remains of the creation. In his words: “Science and religion are two of the most potent forces on Earth, and they should come together to save the Creation.”

It seems ironic, with the elevated view our church holds toward the original act of Creation, that any of us would be indifferent toward caring for it. Yet, for the most part, Adventists and other Christians have stood idle while nonbelievers have taken the lead in creation care. If we would work together, imagine our opportunities to witness, especially to those most in need of a knowledge of Christ!

Personally, I am proud to belong to a church that takes the study of God’s second book—nature—seriously. The Adventist Church has embraced environmental stewardship with several official statements.10 With these statements, the denomination acknowledges that “the ecological crisis is rooted in humankind’s greed and refusal to practice good and faithful stewardship within the divine boundaries of creation.” But in spite of these statements of support, the church’s institutions currently allocate negligible resources toward what could be a powerful witness via creation care.

Although sin has marred God’s original creation, we can still see His handiwork. We have been tasked to ensure that the signature of God’s handiwork remains for all to see and benefit from. It is a gift from God; we show our gratitude by appreciating it. We can also contrast the present creation with that of the original, which will one day be restored. We have been given a brief glimpse of how different things will be one day for the iconic predator of Yellowstone: “The wolf will live with the lamb, the leopard will lie down with the goat, the calf and the lion and the yearling together; and a little child will lead them” (Isa. 11:6).

Now, that’s an ecosystem we should all long to experience, and it’s one that I will want to study one day!

William K. Hayes, Ph.D., M.S., is a professor of biology and director of the Center for Biodiversity and Conservation Studies at Loma Linda University.

Considerable scientific evidence indicates that the earth’s temperature has fluctuated naturally over time, based on geological features, ice cores, sediment cores, tree rings, historical accounts, photographs, and thermometers. For example, a period of relatively balmy temperatures, known as the Medieval Warm Period, occurred from about A.D. 800 to 1300, followed by a relatively cool period, dubbed the Little Ice Age, from about A.D. 1300 to 1850. During the past century the planet has been gradually warming, a trend often referred to as “global warming.”

The concept of global warming is often misunderstood and misconstrued. Although some dismiss it as a hoax,

global warming is a scientific observation based on analyses of data from approximately 6,000 thermometer stations forming the Global Historical Climatology Network. The data unequivocally reveals a warming trend during the past century, resulting in melting glaciers, melting of the Arctic ice cap (but not the Antarctic ice cap), and rising sea levels. The trend has been inconsistent: warming waxed strongly during the early and latter decades of the 1900s and waned somewhat during the mid-1900s and early 2000s.

Although virtually all scientists agree that the earth is warmer today than it was a century ago, there is less agreement about the causes of global warming.

Anthropogenic global warming is a scientific hypothesis postulating that global warming is caused primarily by human activities. The evidence is simple. Scientists have known for more than a century that greenhouse gases occurring naturally in the atmosphere trap heat, and that burning fossil fuels, deforestation, and certain agricultural practices release massive amounts of greenhouse gases (especially carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrogen oxides) into the atmosphere. Because atmospheric greenhouse gases and temperatures have both increased since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, it is logical for scientists to hypothesize that there is a cause-and-effect relationship.

Today there is a strong consensus among climate scientists that human activities are the major culprit for rising temperatures, but they recognize that climate is also affected by natural factors, such as variation in solar radiation and volcanic activity. Regardless of the causes of global warming, many scientists predict catastrophic impacts on natural ecosystems and human societies if global warming continues. If indeed human activities are the major cause of global warming, some believe that only a concerted effort led by governments can mitigate the adverse effects of a hotter and more crowded planet. This is a major point of contention among the skeptics, including some prominent scientists who object to government intervention. Some skeptics deny that the planet is warming; others accept the reality of global warming but believe it has ceased. Although some skeptics concede that human activities affect climate, they all believe natural factors have a much stronger effect.

Floyd Hayes, Ph.D., is a professor of biology at Pacific Union College in Angwin, California. Hayes’s research focuses on the ecology, behavior, and biogeography of birds and symbiotic relationships of coral reef organisms.

According to the Genesis account, the original diet for humans was different from that of animals. After the Fall, the foods for human consumption also included those originally reserved for animals. Subsequently, animals became part of the human diet. Thus, the trophic competition started on our planet. Not only humankind was now eating the food assigned to animals, but also the animals themselves. This has brought about profound consequences.

Today the market offers a variety of foods to nourish our bodies. Just as different types of foods at the market have different prices, the production of each type of food has a different environmental cost. In other words, the environmental footprint and the production efficiency vary from food to food. Raising animals for human food is an intrinsically inefficient process.1

As we move up in the trophic chain, there is a progressive loss of energy and an increasing use of resources. Growing grain to feed animals for human consumption is obviously less efficient than using the same grain to feed humans directly. The amount of grain needed to produce the same amount of meat varies from a ratio of 2.3 for chicken to 13 for beef. Using agricultural data from California, we have shown that the production of protein from beef requires 18 times more land, 10 times more water, 9 times more fuel, 12 times more fertilizer, and 10 times more pesticide than the production of the same amount of protein from beans.2

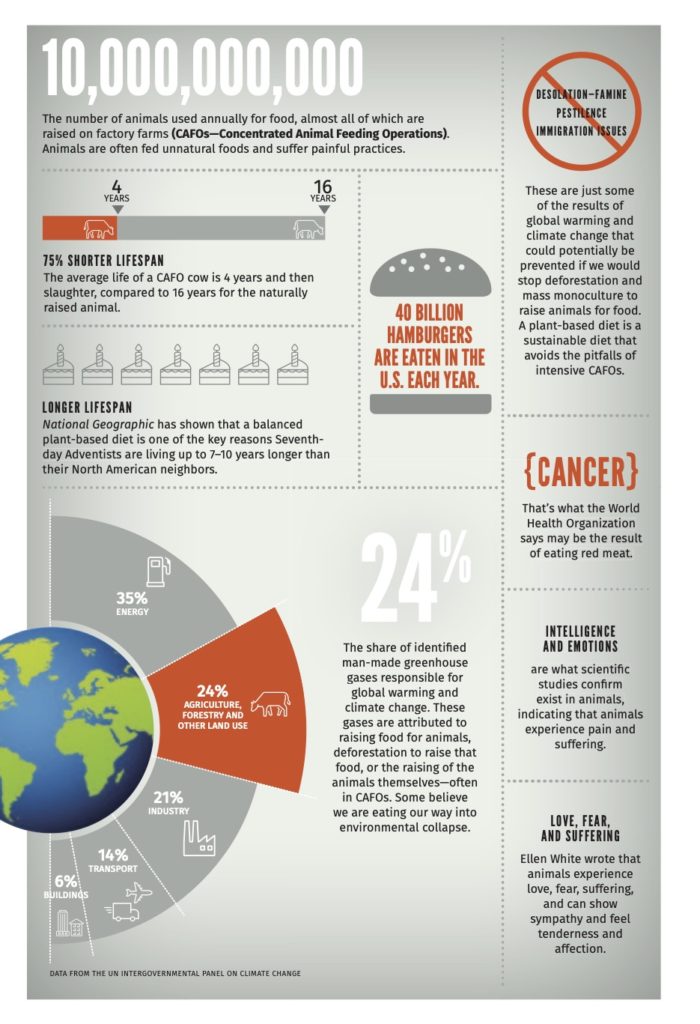

Meat and dairy products are also responsible for a hefty share of the environmental burden of food production. Modern animal farms damage the environment by the concentration of animal waste and by chemical runoff to water and land, causing many problems such as surface and groundwater contamination, oceanic “dead zones,” soil degradation, habitat change, and biodiversity loss. Meat production also pollutes the air, contributing disproportionately to greenhouse gas emissions (carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide) to the atmosphere. We have found that the emissions of acidifying substances, pesticides, and toxic metals are, respectively, seven, six, and 100 times greater for meat protein compared with soy.3 Thus, the intensive production of meat is considerably more taxing to the environment than nutritionally equivalent plant protein foods.

As meat production has multiple detrimental effects on the environment, the consumption of meat has deleterious effects on human health. Recent findings from the Adventist Health Study reveal that those who consume meatless diets enjoy better health and longevity, while at the same time reducing their carbon footprint by 30 percent, compared to those who eat meat regularly.4 Following meatless diets promotes simultaneously human and planetary health. With this dietary choice, we honor God, not only by taking care of our body, the temple of the Holy Spirit, but also of the “cosmic temple,” God’s nonhuman creation.

1J. Sabaté and S. Soret, “Sustainability of Plant-based Diets: Back to the Future,” American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 100 (2014): 476S-482S.

2J. Sabaté, K. Sranacharoenpong, H. Harwatt, M. Wien, and S. Soret, “The Environmental Cost of Protein Food Choices,” Public Health Nutrition 18, no. 11 (August 2015): 2067-2073.

3L. Reijnders and S. Soret, “Quantification of the Environmental Impact of Different Dietary Protein Choices,” American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 78 (2003): 664S-668S.

4S. Soret, A. Mejia, M. Batech, K. Jaceldo-Siegl, H. Harwatt, and J. Sabaté, “Climate Change Mitigation and Health Effects of Varied Dietary Patterns in Real-life Settings Throughout North America,” American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 100 (2014): 490S-495S.

Joan Sabaté, M.D., Dr.P.H., and Samuel Soret, Ph.D., M.P.H., are professors of nutrition and environmental health, respectively, and codirect the Environmental Nutrition Research Group at Loma Linda University’s School of Public Health, California.

Seventh-day Adventists value living simply, modestly, and without excess.1 We live out our values through our diet, our practice of Sabbath rest, and our choices as consumers. At its core, Creation care is based on these same principles.

A balanced, plant-based vegetarian lifestyle, long adhered to because of health benefits, is also gentler on the planet. Switching to a plant-based diet reduces global hunger, improves water quality, and reduces the amount of forest destroyed each year in the expansion of the cattle industry.

We Seventh-day Adventists observe the Sabbath, a day in which God rested from work and commanded His children, their employees, and the animals in their care to rest as well. In this practice of resting from our work and our shopping, we rebel against a consumer culture that pushes us to do more, accumulate more, and covet more.2

Our practice of Sabbath rest must change the way we live our lives the rest of the week so we are mindful of the forests that were cut down to build larger homes, the minerals mined so we can juggle three electronic devices while watching TV, and the pesticides, fertilizers, and herbicides sprayed so we can add a few more items to our closets. On the Sabbath we remember the God who provides for all our needs so that we may consider the needs of others.

With more than 7.3 billion people in the world, there are limited amounts of food, medical supplies, and other commodities for every person on the planet. Every choice in the direction of excess takes away from the basic needs of others. We wield a tremendous amount of power with our credit cards.

How can we use that power? Learn where our products come from, and where our waste goes. Buy used or recycled products. Take care of what you have. Purchase only what you need. Avoid plastic products and packaging. Drive less. Bike or walk more. Buy seasonally appropriate foods grown locally. Plant a garden. Make your own food. Compost green waste. Value the living things God created. Ask your representatives to vote for policies that protect the water we drink, the air we breathe, and the natural spaces that form God’s second book. Choose to live simply so that others can simply live. (See more tips at www.50waystohelp.com.)

God has provided for our needs. Let’s carry our Sabbath rest with us throughout the week, guided by the principles of simplicity, modesty, and limited consumption.

Rest. We have enough.

1Ellen G. White, Testimony Treasures (Mountain View, Calif.: Pacific Press Pub. Assn., 1949),vol. 2, p. 553.

2Barbara Brown Taylor, The Practice of Saying No (Nashville: Harper-Collins Publishers, 2012), pp. 1-26.

Melissa R. Price, Ph.D., is an assistant professor in the Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Management at the University of Hawaii at Manoa.